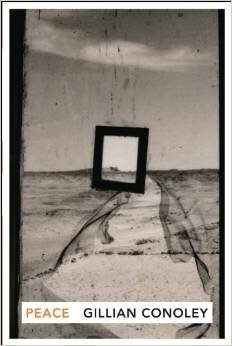

PEACE

BY GILLIAN CONOLEY

OMNIDAWN, 2014

978-1890650957

Gillian Conoley’s new book of poetry (Omnidawn, 2014) is appropriately entitled Peace because it seems to aim at a kind of reconciliation: with the self, with family, with lovers, with the digital world, and with larger abstractions such as death and the occasional “God” or Christ which she infrequently refers to—but which seems to harbor in the vast undercurrents of the text. Her book is contingent upon a very austere subjectivism, but not without a very oblique, if not unintentional sense of humor. The subjectivism threads through the trajectory of the book in a very meaningful way, and yet the manner in which the subject relates herself to the situations she narrates seems as if through an opaque lens. And the opacity that prevails in its surrealistic bent could make the reader feel like he or she is sleepwalking through a very interesting and memorable dream. It is this which binds the momentum of the book and allows ample room for the reader to imagine, and to perhaps free-associate the given text with numerous other stories, most especially if he or she is of a writerly audience.

I don’t know if Conoley is influenced by Gertrude Stein, but there are certainly echoes of Stein in her work. For instance, in her poem A Healing for Little Walter she succeeds in telling the story with brief, syntactically awkward and obscure sentences: “A blue peal bent so far back it’s red./ Little Walter, beasts looking solemn at you/from the other side./Tina still rising./Turn and run./Gold fill,/Gold leaf fill./Fishbone thereby shall we see the light.” Stein, of course inherited a subjectivism which was obscured and hidden beneath the trail of her glottal-stop disordering of sentences, and yet the reader must conjecture who the speaker is and what she might be aiming at. Later in Conoley’s poem: “Gold leaf, gold leaf fill./Crying and wailing with our toy harmonicas/in a space gone unbolt into/a blueness sucking in the sun…” Throughout the poem she repeats the line: “Gold leaf, gold leaf fill…” which if the reader meant to construe this she or he might consider the gold leaf and its fullness in autumn, both in relation to the world and the consciousness of the self.

One of the most beautiful poems in the book is Experiments in Patience II. It reads almost like a haiku: “Family more/than genetics/and laundry/sweep the earth/in your/cemetery slippers/one foot slipping out…” In other words, and if I were to translate this literally and fill in the blank space:

My family is more than simply the genetics I inherit.

Defined by more than the loads of laundry I do each Sunday,

The routine of it like the years I’ve spent growing up

And spinning stories for the sundry experiences.

Family, like laundry, is also the routine of death,

Softly walking upon the graves of relatives,

And never quite letting go…

The incomparable phrase, “sweep the earth in your cemetery slippers” is what allows the poem a very celestial, if not other-worldly sensibility. It is also as I said the essence of the book’s slow and euphoric sleep-walk. Of course, there is a sentiment here, as there is throughout the book, which is not tear-jerking, but rather skin-tingling and evocative of a yearning for a higher spiritual plane.

And Conoley’s book is certainly not without its spiritual element, if not defiantly Christian. For instance, in her poem I Am Writing an Article (Johnny Cash) she asserts “Christ newly staked and writhing/in the heart/in the door-wide chest/in the overall black tower of you…” Here, Christ is a conflicted image of torture, altruistic love, and within his own antithesis.

Conoley’s speaker travels through spiritual planes which exist and yet clash with the digital world she inhabits, such as in the poem “an oh a sky a fabric an undertow:” “The GPS navigational finding device/enhance search/the overly/Google mapped,/severe lack of frontier in the world…” And here, “in mass human’s estranging light” (The Patient) it is evident that the world she sees does not quite reconcile with the world she must envision. Technology has led a mass of humans to begin “exploring the sewers,/recording/sounds of manhole covers as cars…” (an oh a sky a fabric an undertow), perhaps attempting to excavate the inevitable deaths that come with the human condition. It is without doubt that the speaker in Conoley’s poems sees herself as wholly a part of the human condition, and yet the book attempts to reconcile the conflicts which are attached to this.

I would highly recommend reading Gillian Conoley’s book, especially if you’re concerned with the irreconcilable elements of the status quo, with the larger more universal concerns about family and the self, and with the instabilities with which we are faced in the world as it stands. Conoley’s book has the transcendent qualities that future generations will be reading and considering, even after this generation has “[swept] the earth in [its] cemetery slippers.” A must read, for this world, and beyond.

{ 0 comments… add one now }