Canada, it’s spring-break time. We’ve already got trees budding. Actually, many schools have gotten the whole Winter Olympics off for two or three weeks of extended spring break drunkenness. I’ve been glued to CTV for the last week or so, watching my new favorite sport: curling. No joke, this game is intense. It’s the skill of bowling with the strategy of chess. Not to mention, curling and hockey are two of the few things that get Canadians riled up (they go from passive agressive to just plain aggressive).

In the spirit of breaks from routine (are two weeks of blog posts long enough to be considered a routine?), I figured it would be good to take a break from the Grossman inspired posts and do a little reflection on a recent article in Wired magazine: And in the spirit of Spring, I want to see if I can connect it to W.C. Williams.

Ever since I read an article on cloud computing and Google’s ability to translate web pages based upon its database alone (that is, nobody programmed the various language rules in it; it literally translates via algorithm), I’ve been interested in Google’s relationship with language. Now, any of you who have used Google Translation know it’s pretty awful, but the idea alone is impressive, and there’s no telling where improvements will take it.

This particular article goes under the hood of Google’s search engine, and we find out the real difficulties lies not so much in web crawlers, page ranking, or any of the stuff Google is known for (although, that is certainly a feat), but rather interpreting the desires of the Googler:

“We discovered a nifty thing very early on,” Singhal says. “People change words in their queries. So someone would say, ‘pictures of dogs,’ and then they’d say, ‘pictures of puppies.’ So that told us that maybe ‘dogs’ and ‘puppies’ were interchangeable. We also learned that when you boil water, it’s hot water. We were relearning semantics from humans, and that was a great advance.”

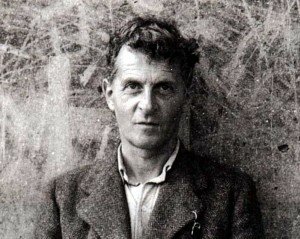

But there were obstacles. Google’s synonym system understood that a dog was similar to a puppy and that boiling water was hot. But it also concluded that a hot dog was the same as a boiling puppy. The problem was fixed in late 2002 by a breakthrough based on philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein’s theories about how words are defined by context. As Google crawled and archived billions of documents and Web pages, it analyzed what words were close to each other. “Hot dog” would be found in searches that also contained “bread” and “mustard” and “baseball games” — not poached pooches. That helped the algorithm understand what “hot dog” — and millions of other terms — meant. “Today, if you type ‘Gandhi bio,’ we know that bio means biography,” Singhal says. “And if you type ‘bio warfare,’ it means biological.”

Did you catch that? Google uses Wittgenstein…Holy Mother of all snake-eating-its-own-Postmodern-tail!

Google, of course, is probably at the forefront of product innovation. Google has created an environment where failed ideas are OK, a sort of decentralized and messily creative workplaces that capitalizes on an excess of time and resources. Knowledge workers rejoice! (See and )

But that wasn’t what caught my attention most of all. It was this:

One unsuccessful search became a legend: Sometime in 2001, Singhal learned of poor results when people typed the name “audrey fino” into the search box. Google kept returning Italian sites praising Audrey Hepburn. (Fino means fine in Italian.) “We realized that this is actually a person’s name,” Singhal says. “But we didn’t have the smarts in the system.”

The Audrey Fino failure led Singhal on a multiyear quest to improve the way the system deals with names — which account for 8 percent of all searches. To crack it, he had to master the black art of “bi-gram breakage” — that is, separating multiple words into discrete units. For instance, “new york” represents two words that go together (a bi-gram). But so would the three words in “new york times,” which clearly indicate a different kind of search. And everything changes when the query is “new york times square.” Humans can make these distinctions instantly, but Google does not have a Brazil-like back room with hundreds of thousands of cubicle jockeys. It relies on algorithms.

The Mike Siwek query illustrates how Google accomplishes this. When Singhal types in a command to expose a layer of code underneath each search result, it’s clear which signals determine the selection of the top links: a bi-gram connection to figure it’s a name; a synonym; a geographic location. “Deconstruct this query from an engineer’s point of view,” Singhal explains. “We say, ‘Aha! We can break this here!’ We figure that lawyer is not a last name and Siwek is not a middle name. And by the way, lawyer is not a town in Michigan. A lawyer is an attorney.”

This is the hard-won realization from inside the Google search engine, culled from the data generated by billions of searches: a rock is a rock. It’s also a stone, and it could be a boulder. Spell it “rokc” and it’s still a rock. But put “little” in front of it and it’s the capital of Arkansas. Which is not an ark. Unless Noah is around. “The holy grail of search is to understand what the user wants,” Singhal says. “Then you are not matching words; you are actually trying to match meaning.”

My current job is teaching upper level writing to ESL students who are entering graduate school. Most of them will go on to do MBAs, but I try to give them a heavy dose of the liberal arts, which many of the students (especially ones from China) are lacking. It’s an incredibly frustrating process, at first, but it has turned into the best kind of reward, as I get a glimpse of my own language and system of thought from an outside (alienated?) perspective. For as many discernible, overarching truths and rules about the language, I often find the same number of beguiling nooks and crannies, particularities that indicate a long history of human choice and situation enshrined in our very words. Almost everyone knows this about language, but to actually encounter it on a regular basis is a bizarre experience.

I think my experience teaching is the same experience that Google’s engineers must deal with: Why do we associate certain things, and what complex process takes place in our brain that allows us to instantly recognize them? The question of lines in poetry adds a layer of complexity to this question. Grossman says that “lineation” is one of the defining qualities of poetry (even prose poetry is defined by its lack of lines, isn’t it?). As I was attempting to write poetry for the first time in high school, I remember obsessing over my lines. I could never understand why I wanted to break a line here one day and there on another day. As I write, I feel pretty confident about cutting my lines. That isn’t to say I still don’t play with line breaks, but I have a pretty intuitive sense of when to hit the Enter button. Sometimes I break a line for the sake of a playful slight rhythm, but usually it comes as a sense of whim–it just seems right. Is this an intuitive sense that has a core? Or is it really just whim?

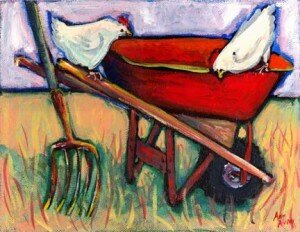

This leads me to my question: How would Google parse a poem like W.C. William’s It reminds me of a passage from a paper I wrote in the beginning of grad school:

Even though this poem is essentially a sentence, each image is carefully isolated by means of juxtaposition. Each stanza contains images that are a juxtaposition within itself according to the line breaks: “depends” versus “upon” (two directional words going in opposite direction), the particulars of the wheel barrow (its redness and wheel[ness]) versus the wheel barrow in its wholeness, the glaze of rain versus the rainwater, the chickens versus their own whiteness. The details of the things are pulled apart and highlighted, bringing out a rich multi-faceted view of each object. Williams’ accomplishment is almost that of the cubists, allowing the reader to see these objects in many different ways, from the different angles of detail. Yet despite this almost excessive juxtaposition, the poem has a unity. It does not communicate the same fractured nature that a painting like Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase. Rather, this poem explores the unity of objects, their interconnectedness, while also evoking the particularities of objects and, in some sense, how they vie with one another. What is even more striking about this poem is how commonplace it is. These are objects that many Americans in Williams’ time could see on a regular basis. For Williams to find so much juxtaposition and still unity, to be so common and yet absolutely metaphysical is a feat. More important here, we can see the way he perceives language. Each word is isolated either visually or by juxtaposition in the same way each imagistic object in the poem is isolated. This is one thing Williams does often in his poetry: isolate each word visually, either through an extreme sparseness of form or by simply leaving a word on a line by itself. What would today be considered gimmicky by most MFA students, Williams accomplishes with verve in a way that is not gimmicky in the least. This is because Williams largely helped pioneer this technique, but also because the reader senses the whole power of idiom behind Williams’ language. Its commonality is the source of its power. The idiom arises from the commonplace here. And more importantly, Williams communicates this idiom through objectness.

That passage contains perhaps one of the most absurd phrases I’ve ever written: “the chickens versus their own whiteness.” (No post-colonial analysis, that!) But no matter what you think of my analysis, the question of where these words are “broken” from one another and why is a question that I suspect Google could never answer in the form of an accurate search. Google can tell when “little rock” means the capital and not a small pebble (or some sort of midget music genre), it’s true, but humans are capable of something even more complex than that: breaking things apart and still recognizing the relationship. As the passage from my paper indicates, I believe this ability stems out of idiom (in William’s case, the American Idiom).

That passage contains perhaps one of the most absurd phrases I’ve ever written: “the chickens versus their own whiteness.” (No post-colonial analysis, that!) But no matter what you think of my analysis, the question of where these words are “broken” from one another and why is a question that I suspect Google could never answer in the form of an accurate search. Google can tell when “little rock” means the capital and not a small pebble (or some sort of midget music genre), it’s true, but humans are capable of something even more complex than that: breaking things apart and still recognizing the relationship. As the passage from my paper indicates, I believe this ability stems out of idiom (in William’s case, the American Idiom).

Ironically, Google sees everything as fractured. When you search johnny cash hurt, Boolean logic looks for johnny and cash and hurt. Google uses modified Boolean logic and has accomplished the ability to tell when certain words probably go together.

Now for the second order language intelligence of poetry: can Google understand line breaks? Could Google help us become better writers?

I’ve been re-working some translations of poems by the Argentinian Hector Viel Temperley – similar issues arise in translation, especially of poetry, though they’re transposed transposed – with regards to idiomatic phrases, and carrying the sense of a sentence. Doing the translation work, one feels the brain trying to come up with algorithms for valences of meaning, intention, style. Nice post.

I should add that the translations I’m re-working are in fact mine, from ten years ago. So there’s another level of recalibration going on there too.

Great article. I am reminded of my experience with certain students who have forms of mild asbergers. I have had at least two students with asbergers who were gifted poets, but suffered from emotional disconnects (not necessarily a disadvantage when it comes to the inventive and surprising effects of language divorced from normal patterns and overly familiar tropes of empathy).They certainly experience emotions, but are often oblivious to the normative tropes or social contexts of emotion, or what effect certain words might have on others. There is also a kind of candor, a lack of inhibition that makes them seem insensitive to others feelings.

In the case of these students, precision was not the problem. They were poor at entering what I’ll call “aproximate feeling modes.” They had to guess, and it was extremely difficult for them when they guessed wrong and caused someone pain, or recieved looks of shock. The one student had straight A’s, wrote wonderfully precise lyrics, and was attractive, so no one knew right away she suffered any form of asbergers. In many ways proper, even demure, she often dressed in a provacative manner and was shocked and appalled when it drew notice She didn’t get mst jokes, though obvious forms of irony were understandable to her. An example of her disconnection would be the time she attempted to console her boyfriend in a room full of friends and strangers for having suffered a rejection: “Don’t feel bad Tommy,” She said, “Tonight, when we go home, I will give you a blow job.” She said this straight faced. She was shocked, and deeply disturbed when people laughed in shock, or incredulity. She tried to explain, highly offended by their laughter: “Tommy likes blow jobs. They always make him feel better.” She was not trying to shock anyone. She was not being bawdy. She was computing: “Tommy is sad. I don’t want him to be sad. Blow jobs please him. It will cheer him up.” In some respects, it resembled the “errors” google encountered, the problems with nuance and dstinguishing the difference between a hot dog, and boiling a dog, but nothing she said was incorrect. She just did not get certain forms of social context. She was not aware of the effect such words coming from the mouth of an attractive, otherwise brilliant girl would have. Those emotional tropes she did get, either through painful experience, or through an educated guess, she enforced more stringently than any normal person. IF someone said “shut up,” or anything smacking of rudeness, she was the first to upbraid them. Her problem was not error, not a lack of precision, but an inability to understand aproximations, the “sort of’s” of verbal and social context.

We know the brain is adaptive enough to have separate areas for precise calculation, and approximation. In cases where people have had the part of the brain damaged that allows for precise calculation, they do not say 2+ 2 equals 4, (unless they make a lucky guess), but they also do not say 2=2 equals 4540. If their ability to aproximate is still intact, they may say five or three or six, but they will not be absurdly far off the mark. It is this “approximate” sense by which we may be distinguished from the computer. A computer is capable of error, but not judicious error, and certainly not of spending the greater part of its life moving through a series of judicious and acceptable aproximations. Many people are willfully oblivious, and some, though they don’t have asbergers, have some form of emotional disconnect (In Meyers Briggs they would call such people radical T’s—thinkers with a buried “tertiary” feeling sense). In terms of poetry, this can often be an advantage because the same things that in a social context might prove bizzarre, come off as refreshing, incongruous, or vividly odd in a line or series of verse lines. The poem you quote by Williams has this element of freshness since, in its own way, it seems as odd, and strange as the girl with Aspergers saying: “Don’t worry Tommy. Tonight I will give you a blow job.” Much of modernism and post mdernism has been a dismantling of expected tropes of emotion, a greater emphasis on sensing and intuitive functions. The Red Wheel Barrow can reference no expected trope of emotion. People unfamiliar with the modernists, non-petry students (and many poets as well) will shake their heads and say: “Huh?” It is not so much shock as it is a suspension of the usual connections in meanings, both in the poem, and within the historical context of poetry. Suppose Williams had written:

The red wheel barrow glazed with rain water

beside the white chickens is vital to me.

The reader might understand this as a poem about the “beauty” of the pastoral life, a decidely bad poem. but it would not arrest or confound his intelligence. It would not make him go “huh?” Perhaps a better example would be Nabokov’s intentional mangling of a Robert Lowell line when he took Lowell to task for what he considered an awful translation of Mandelstam. He wondered how Lowell would like it if Nabkov translated his phrase “leathery love” into the “football of passion.”

It seems to me much of modernism and post mdernism is about exploiting these radical disconnects, creating what Burke called a perspective by incongruity. One final note:

Another student of mine with Asbergers recently lost her pet rabbit. She wanted to give him a proper burial. She was inconsolable, but the ground up here is still too frozen. Someone kindly suggested she have the rabbit cremated. This drove her to pained distraction and she said: “I won’t cook Billy! How awful!” She was right about the bare essentials of cooking and burning being identical, but she did not aprehend the person’s intentions, or the differences between cremating a beloved pet and cooking it. Aproximation,, the “sort of” might be how we move through both our visible world and our language systems. We construct a narrative, comprised partly out f past experience and partly out of a hard wired ablity to do instant guess work—a series of “sort ofs” by which we somehow arrive at the right place. Avoiding the follies of precision might be as important as avoiding approximations, but bth can lead to sme interesting places such as “the football of passion.”

really enjoyed this post. “Probably” is a good Wittgenstein-type word choice in your conclusion :-

As for the associative stuff from Wittgenstein, my major professor (R.M. Berry) explained it to me as Wittgenstein’s concept of “family resemblances,” again, something humans can process in a flash, but we have to teach computers how to do, since words aren’t literal referents in all cases (e.g. the “little rock” case you mention).

The W.C. Williams link is appropriate–all such linkage is appropriate! … but I wonder if Williams’ process works because of “idiom,” in terms of diction or that it is his use of white space and line breaks that really achieve the effect you describe?

Would an extreme example of this process be Stein’s Tender Buttons? Or is she pushing the unity envelop too far? Or is she saved by writing in prose? (Or how does prose change the game here?)

Micah, Joe – What I did managed to capture from all this was an experience much like putting time destructed moments back together again. Great stuff, thanks. I’m wrapped in a conversation – particle pieces and the process of my own mind. Not to mention the process of how my mind becomes my own. Is it this language thing or that human relation to language thing that never ceases to amaze me.

Glad to find the post, be it through google’s algorithm of who to buzz. Much like the approximation of empty spaces and blow job guessings. Speaking of which, Joe you are the greatest teacher one can have and I have yet to have you. All kidding aside, here’s to the association by word or space between or name and such the likes of places.

to post:

I read that article and also another one. I read that article and also another article. I read William Carlos Williams and I read the Google algorithm. I read the Google algorithm and I read the Tender Buttons. I read algorithmic buttons and I read tender white Wittgenstein. I read a cuban sandwich and I read a book on birding. And I read on birding and I read associations into it. I read on legs and Kafka, on Levinas and on Gertrude Stein. I read the words I write and wrote and reading them on screen. I read an image of a picture of a letter of a character. I read a character and I read a word or two, and then I sleep, or slept, or wrote, or read, and in the cloud I searched for tenderer buttons than these. So little now depends upon the color of a laptop, glazed with ejaculate, alongside the sleeping young woman…

At least, I think so.

You, suck, liking your own post.

I have just read Ray Monk’s biography of Wittgenstein and am now reading some of his works in translation. He is on e of my favourite people.

jean you may enjoy the blog of Daniel Silliman, who writes for thethe. see, specifically his wittgenstein wednesday posts:

*anna jean

Thanks. This is very interesting, especially about the newly discovered manuscripts. I have read W’s Notes on Colour and am now reading On Certainty. I can’t follow the math, but the process of thinking and saying is fascinating.Ray Monk has a very good, brief book called How to Read Wittgenstein. The photographs don’t surprise me. W was very hands-on and interested in making things.

What’s the best place to recommend a Wittgenstein virgin to start?