March 2010

The time has come to reveal (I think) the source (for those who don’t already know) of The The Poetry’s name, namely, “The Man on the Dump” by Wallace Stevens. is a link to the full text.

One of the things that may irritate a post structuralist reader about Auden is that he delights in “knowing” things-even those things which are ugly and disastrous to know. For example, his greatest praise of old masters: “About suffering, the old masters they were never wrong.” Auden likes being right. He likes being elegant. He likes making a point in as clever a way as possible. He even likes his ambiguity to be gin clear. This annoys readers, especially those who come out of the post modernist wood work to feed on endless non-commitments, non-linearity, statements that dissolve and are contradicted or made impotent by the sheer process of deconstructing one’s deconstructions. Stevens claimed that a great disorder is an order (well ahead of chaos theory). Post structuralism with its absolutist hatred of saying anything is, well, to put it in the language of my forbears: fucking boring. Auden, at his worst, is also a bore. He can be pedantic, over bearing, a spewer of opinions, a snob, a writer of high falutin doggerel. At his best, he is the greatest poet to come out of the formalists, and for the same reason Ashbery is probably the greatest poet to come out of the post structuralists: because he is good at saying what he enjoys saying, because he takes great delight in his own utterance for its own sake, because no old bone wearies him if he can find a happy way to chomp on it. This is no small virtue. If a poet is not enjoying his own spew, what damned good is he? Auden’s ability to wrap things up annoys a reader only if that reader is deaf to the sonic joy of Auden cracking wise. The pleasure in Auden is not in what he says, or even in how he says it, but in the sheer pleasure he takes beyond how or why—a pleasure that, in his best poems, becomes a palpable presence throughout. When I want to witness a poet enjoying himself I turn to Ashbery or Auden. With great craft and skill, they sit in their respective sand boxes, and both are infantile in the best sense. At any rate, lets inspect one of Auden’s more famous poems,the imitation ballad, “As I Walked Out One Evening.”

As I walked out one evening,

Walking down Bristol street,

The crowds upon the pavement

were fields of harvest wheat.

And down by the brimming river

I heard a lover sing

Under an arch of the railway:

“Love has no ending.”

We are in traditional ballad country the second Auden writes “As I Walked Out One Evening” (see “The Streets of Laredo”). He is not mocking the structure or form of the ballad (except perhaps the way a lover would tease his beloved); he is reveling in the cliche. He trusts his own ability to have fun with cliché (something Ashbery also trusts). He is using what is called “eights and sixes,” a tetrameter line followed by a trimeter; and, to give it the “feel” of an informal ballad, he is augmenting or truncating the syllable count, dabbling in hypercatalectic, and acatalectic lines (one syllable more or one less). But of all the fun he is having in these first two stanzas, I’m sure nothing pleased him more than the wrench rhyme, worthy of a hip-hop MC of: “sing/ending.” Auden, in the next two stanzas, delights in one of the oldest tricks in the book: adynaton, the lover’s appeal to the impossible, the great brag of the lover plighting his troth:

“I’ll love you, dear, I’ll love you

Till China and Africa meet,

And the River jumps over the mountain

And the salmon sing in the street,

“I’ll love you till the ocean

is folded and hung up to dry

And the seven stars go squawking

Like geese about the sky.

“The years shall run like rabbits,

for in my arms I hold

The flower of the ages,

and the first love of the world.’

First, note the vowel rhyme of hold and world. And as for the adynaton,such wonderful boasts no longer exist in our poetry, which shows its sad and tragic “humility” to be far more arrogant and stingy than this delight in the lover’s form of boasting hyperbole. Only in songs does this sort of boast still thrive, for example, when Tom Waits insists: “I’d shoot the moon for you.”

Auden can’t let the lover triumph. Modern nihilism must rear its ugly head, or is it modern? The doom of all young love is a common subject of Latin and Greek, and almost all ancient world poetry. Auden knows the difference between originality and novelty. Novelty can only be interesting once, the first time. Originality is that which is suddenly ancient, and anciently sudden. Orignality has a nomative power, and can be intersting and pleasurable again and again because it manages to touch upon origins as well as news. The worst that can be said for pre post modern poetry is that it lacks the surprise of novelty. The worst that can be said for post modernist poetry is that it opts for novelty and confuses it with originality. I do not believe in cliched tropes. A trope can be tired and hackneyed only if the poet lacks the energy to enliven it. Carpe diem is still trembling in the shadows, waiting to be felt up by a daring poet. At any rate, Auden takes great delight in disillusioning the lover. Some of those stanzas:

“In head aches and in worry

Vaguely life leaks away,

And Time will have his fancy

Tomorrow or today.

“The glacier knocks in the cupboard,

The desert sighs in the bed,

And the crack in the tea cup opens

A lane to the land of the dead.

The images here would be surreal if they were not used to a purpose, but they are far from the effect of surreality which is to tweak the unconscious, the intuitive or sensing faculties—the irrational. This is the rational, didactic use of absurdity through thought and feeling to make a point, and the point is pretty much the same point made when Nash informs us that “Helen’s dust” stops up a bung hole: love is doomed and time ravishes even the most powerful passions.

This aint news, but it is a ritual of “giving the bad news.” which we can tell the poet puts all his craft and pleasure toward. A ritual can be beautiful, even pleasurable by dint of the joy and liveliness with which we perform it, and invest our time in it. To say a truth over and over again is to find the ritual that will make that truth, however awful, portable, and somehow, even more than bearable.

What Auden does in the final stanza, after having time destroy the lover’s troth, is return us to the cosmic impersonality of the river:

It was late, late in the evening.

The lovers they were gone;

The clocks had ceased their chiming,

And the deep river ran on.

This gives the poem the sufficient modernist chill it needs to be more than merely an imitation of ballads, but the real worth of it lies in Auden never believing for a minute that the tropes can be exhausted. How can one exhaust the ancient fear and fever of the blood, the dread and hopelessness of “I’ll love you forever?” Be careful, students, that your sophistication and stupidity in the dadaist, slacker, cynical, “non-linear” sense does not blind you to the pleasures of true nihilism: yes, I know, I know, and on the thousandth point of knowing, my heart still breaks.

<>

Concerning all the recent discussions about memory, recitation, etc, I thought I would try it in my own way. I should disclose that I never recite my own poems from memory at readings. I think it is corny, weird, it makes me uncomfortable, and frankly, to spend that much time memorizing your own work is kind of sick.

<>

I want to rebel against my own ideas.

<>

I tried to write a poem entirely in my head and memorize it. I would never write it down. All editing would take place in my head. Line for line. The entire building and reconstruction could only exist abstractly. No writing as an aid. I would memorize the final poem. I would recite the poem and that is how it could live.

<>

This is how it went: First I had a few lines, but I could only get at it by starting from the beginning over again each time. I imagined the line breaks and pauses to help remember it. I decided maybe I would to add three lines a day. I would imagine the form entirely in my mind. Maybe 12-16 lines total. A good length lyrical poem. It would be difficult.

<>

I felt I was cheating. Picturing a form, with lines, line breaks, and any visual form seemed to me a kind of writing. Since I wasn’t marking anything down, why should there be “lines?” It’s just words in my head. There was also no need for form. When you recite a poem that you’ve seen on the page, imagining the stanzas certainly helps, but for this particular project (and yes it was becoming a project and yes I hate projects!) I felt that if I pictured lines, or stanzas, then that would essentially be the same as writing it on paper, because those forms are meant to see written and seen as a way of organizing thoughts on a page. To be true to the imaginative strength of the mind, it would just have to be a string, the rhythm of which would intuitively generate itself as I repeatedly said the poem allowed or thought it.

<>

To order these words, these thoughts, I began imagining the actually words. Not just the sound. I saw the words in sequence. But to fix the words in an order seemed to me to always constitute a kind of writing. I felt I was cheating. It was also the kind of writing I could not get space from. It would be impossible to reflect upon the poem if I constantly had to carry it around. It would never sit and get cold. I could never see how shitty parts of it were and try and mend it. I got upset. It was becoming a drag on all accounts.

<>

I decided that the only way this poem would be good, and interesting, and truly exist on the level, was if I created it anew from nothing every time I recited it. I would have to make up a new poem everytime. That would keep it from becoming this totally limiting enterprise. Because to go from memory is so safe…the only danger is forgetting, and thats more of a social anxiety than actually having anything to do with whats at stake in the greater art of it. Because to memorize my own thoughts, as megalomaniacal and funny an idea as it was, was really just writing another poem, and it wouldn’t be good. I am very happy to have moved on from this ludicrous idea.

A Green Crab’s Shell

Not, exactly, green:

closer to bronze

preserved in kind brine,

something retrieved

from a Greco-Roman wreck,

patinated and oddly

muscular. We cannot

know what his fantastic

legs were like–

though evidence

suggests eight

complexly folded

scuttling works

of armament, crowned

by the foreclaws’

gesture of menace

and power. A gull’s

gobbled the center,

leaving this chamber

–size of a demitasse–

open to reveal

a shocking, Giotto blue.

Though it smells

of seaweed and ruin,

this little traveling case

comes with such lavish lining!

Imagine breathing

surrounded by

the brilliant rinse

of summer’s firmament.

What color is

the underside of skin?

Not so bad, to die,

if we could be opened

into this–

if the smallest chambers

of ourselves,

similarly,

revealed some sky.

-Mark Doty

I’m currently in a class concerning Animal Studies in the Comparative Literature Department in which the word “anthropomorphism” is a swear word. The argument is that anthropomorphism is anthropocentric, and thereby undermines the possibilities of the animal’s consciousness by placing the human in a superior (and dominating) role. It should be noted that while I think this all well-argued and slightly interesting, when it comes to poetry—it’s a large load of nonsense. We’d have to knock out some pretty significant poems in our extended canon were we to castigate anthropomorphism the way they are proposing. At least for me, and for a long trailing history of ancestor poets behind me, anthropomorphism is the stuff I (we) live for. And if it’s a profane thing, then @#*& you, Comp Lit people. (It should also be noted I am the only poet in that class, and I am looked at at least twice during every session as if I were a really cool but leggy and crawly beetle that you’re grossed out by but can’t look away from.)

But you haven’t failed me completely, pedants. You’ve brought into the sphere of my vocabulary a new term that I am finding far more interesting and applicable than the “horrors” of anthropomorphism: ZOOMORPHISM. Of course it exists the other way around! Why shouldn’t we, egotistical, dominating humans that we are, take animal traits and ZOOMORPHIZE ourselves to further some exploration of consciousness, personality, experience, etc.? Now this—this is good. And now that you bring it to my attention, my esteemed scholars across the way, it’s obvious that it’s zoomorphism that is the most interesting, and the poetry that has been most profoundly affecting for me is that which ventures to gain perspective by putting on another set of eyes entirely not human, kicks up the dirt with its daring hooves, flares its nostrils and doesn’t give a damn about drooling or snorting.

And then comes Mark Doty, with this genius little (enormous!) poem, which anthropomorphizes a crab shell to aid in the zoomorphism of the reader. I mean really, the man has DONE IT. My temptation to pass out this poem to my peers in Pedant Class as a semi-guerilla act of poetry warfare is barely tameable. But I’ll refrain from my nerdling rebellious impulses and just be tickled by the possibilities of what once could have been in this grand ruin of a crustacean edifice that Doty has given me. Beyond that imagining—beyond “what color is the underside of skin?”—just those remains, just that royal palace of a shell, with “such lavish lining!” is so enchanting, so incredibly enticing that I can’t help but want to go beach combing this instant and stare into a crab shell as I never have before (Wanting a reflection? Wanting my own to make a home out of?). This is the kind of poem that changes how you proceed in the world after you read it. A crab shell is NEVER just a crab shell after this, nor should it ever, ever, ever be. If you catch my (sea) drift.

If ever I was called a hermit crab by overly-social friends pressing me to leave my precious lair (and oh, it has happened!), I wish I’d rebutted with this poem. Who would ever want to leave their shell if it were anything like that shell? (Though Doty’s crab isn’t a hermit crab, probably just a common littoral crab. Still.) Magical creature that he’s shown us! Imagine it in life, scuttling around, clickety-clacking on shore pebbles, a little magician with electric green wands! Sigh. Call me crabby, call me (a) hermitic (crab), certainly call me crazy—but thank you, my dear Mark Doty: I forever welcome it all.

So there’s always this double duty, neither to make the best the enemy of the good, nor to make the good the enemy of the best. Scylla and Charybdis. The reason I admire Johnson and Eliot and Empson so much – the thing that holds them together – is that they all think that doing the right thing is steering between two equally dangerous opposite bad things.

Do you remember that Eliot was billed as giving a talk on ‘Scylla and Charybdis’ and he’d realized that they’d simply misunderstood. That is, when he was asked what he was going to talk about, he’d said that these things were always a matter of Scylla and Charybdis and so forth, and this became the title of the talk so that we got a talk on this subject because they’d slightly misunderstood what he was saying. But it’s true to him.

And Samuel Johnson is profound on this. He asked why are we more lenient towards foolhardiness than towards cowardice. If you think of them as being equidistant from the right thing, two opposing faults. Why are we more lenient to the one? And the answer is because it is self-correcting. If you’re foolhardy, you bruise your shins. You find out, you learn from it. If you’re spendthrift, you learn as the miser never does. The spendthrift runs out of money, the miser never runs out of anxiety about money. Equidistant from the true course but one may prove preferable.

We need people to remind us that the good is the enemy of the best and we need people to remind us that the best is the enemy of the good. We need to protect ourselves from the dangers from both flanks.

—Christopher Ricks, interview from The Literateur Magazine

Something in a title suggests everything you could possibly want to say about a certain topic. As in the example of T.S. Eliot’s lecture entitled “Scylla and Charybdis,” mentioned by Ricks above. The title “The Problem of Style” suggested to me everything I wanted to blog about today concerning the evolution of a poet’s style, something I’ve been thinking about while reading through Robert Hass and Henri Cole to prepare book reviews about their new selected works.

Critics and academics—much maligned creatures to whom we should at least be grateful for having something to endlessly argue about—tend to regard style as a fixed thing, an external lacquer or recipe that poets consciously choose, modify, and have to then be evaluated for a/ which style they picked, b/ how well they handled it, and c/ at what expense Style X precluded Y or Z. Two conversations from memory substantiate the attitude I’m talking about, both by formidable minds. Archie Burnett teaching his class at Boston University was talking about John Milton and upon fielding some questions about the make-up of what we identify and label as “The Miltonic Style,” he went on to say “Ah, well, with a great poet like Milton he could have written in whatever style he wanted.” And recently, breaking bread with Daniel Mendelsohn, we entered into a large, hearty and even heated debate on whether or not a writer “sets out to know what he wants to write,”—his point being that whereas an amateur writer may just be throwing darts in the dark, merely provoking “questions,” suggesting possibilities he doesn’t have a finished thought about, the serious and accomplished writer knows exactly what he’s setting out to do, then tackles it with dispatch. I disagree with both of these statements—the first wholeheartedly, the second because of a zillion counter-examples. Milton, supreme artist that he was, wasn’t immobile or unaware of what he was up to, but to think he could have avoided the baroque line, his heightened Latinate phraseology, the robustly complicated syntax, is fanciful. For all his craft and intelligence and arch learnedness, Milton’s rhythmic DNA was predetermined (in a way). People, like poems, are after all a mixture of the given and the made. The made is not what I aim to dispute; but the given needs to be redefined, a little bit.

Style is foremost a tension of contradictions between a writer’s impulses and perception, not an absence of them. In a classical style, a writer’s personality is totally disguised behind the established proportions and prevailing measures of a tradition, or The Tradition, whatever that once meant. In the romantic style, a writer’s style emerges as an indulgence of their impulses and mannerisms that they recognized in past authors and themselves, developing towards “originality.” But originality as we know is at the root of idiocy, of speaking or sounding like someone outside the acquainted norms of the city—the polis. And this is what Samuel Johnson was getitng at when he said in response to a young poet’s manuscript: It is both good and original; the parts that are good are not original, the parts that are original are not good. Johnson, the epitome of the Augustan, classical mindset, looked on idiosyncrasy as a disease, one that had to be tolerated in the presence of a great writer like Swift, great that is for his other qualities, but extirpated in an overrated poet like Thomas Gray, whose diction was remote and eccentric. (I for one love Swift and Gray.)

And yet as Richard Howard has brilliantly written in his essay on Emily Dickinson, it is precisely a writer’s peversities that can make him so good, not in lieu of them, but directly because they were listened to, indulged, cultivated. He argues, shrewdly, that Dickinson’s dashes, capitalizations, peculiar rhythms, coy slant-rhymes are her genius as a poet, not provincial blemises that happen to sit on a great linguistic talent. The opposite point of view can be heard in Eliot’s essay on Blake, where the attitude is: Yes, this man was a great poet, but alas also a home-spun weirdo, who had these troublesome peculiarities that prevented him from being as important as good ol’ Dante. Harold Bloom, dissenting from Eliot (shocker!) has fired back, emphasizing in ‘The Western Canon’ (perhaps tipping the see-saw too much in the opposite direction) that Dante’s centrality to Western literature relies on his extraordinary brazenness, as when he ciphons Beatrice into eternal salvation history (an argument that is found also in Emerson).

But I am digressing between the Classical and Romantic trap, when what I want to talk about is what is akin to both of these modes, intrinsic to writing any poem, regardless of what the tradition it plugs into is.

When we think of style as a pathology—we do artists an injustice, to their deliberation and foresight, as well as to the range of a poet proven over time. Stevens writes in his characterstic mode for his entire life, but between ‘Harmonium’ and ‘The Rock’ the conscious artisan in Stevens decided to become more pared down, less jumpy in his adjective use, and honors the strain throughout his life to speak in the simple sentence.

When we think of style as a choice—we are forgetting that sensibilities are vast and complex and have so many unconscious ingredients, dispositions and biases at work, it’s impossible to say simply why W.C.W. favors the short, clipped line, and Frost keeps to iambic pentameter. One man’s nerves cannot stand noise, another bathes in distortion and static.

One of the problems of style then is when a writer acknowledges a past tendency as a mechanism no longer adequate, or pleasing, or just. True, for the precocious or immensely talented, perhaps this gap is indiscernable, or much shorter—as in a Merrill, who began writing as refined and polished as his very last works. Another exception is the occasional, and rare, writer who assimilates so easily other people’s styles, he can seemingly switch between them—but then isn’t that method their style? Joyce, Eliot, Ashbery: they don’t so much have different styles as styles with immense difference built into them. In Joyce, you see these as discrete effects as you follow his career towards a sea of chaos—but the Joycean tone, flippant, somewhat verbose?, and resigned, that’s there throughout. Eliot willfully goes against his inner discord, his turmoil and polyphony of voices that he discovered in ‘The Waste Land,’ then labors towards a ‘style’ in the ‘Four Quartets’ that is seamlessly regulated, and unified. Ashbery took the opposite route, and after he mastered in his third and fourth books the possibility for disjunctiveness in vocabulary, narrative and form—he has kept going, on and on and on, to this day.

It appears to me that everything that I am saying is grossly redundant, and obvious. So that’s a good place to stop.

The problem of style exists, larger than the unconscious and conscious distinctions I’ve circled around. One way of seeing poems must be not as answers to questions, solutions for the puzzle, or resolutions to the problem—but as a way to discover what the questions are, what puzzles need working out, what problems each writer has in store. If we’re lucky enough, though the problems, like our pathologies, never go away—we do get to master them, instead of them mastering us. That is, one hopes.

comments on :

Journalistic standards have changed so drastically that, when I took the podium at the film circle’s dinner and quoted Pauline Kael’s 1974 alarm, “Criticism is all that stands between the public and advertising,” the gala’s audience responded with an audible hush—not applause.

Over recent years, film journalism has—perhaps unconsciously—been considered a part of the film industry and expected to be a partner in Hollywood’s commercial system. Look at the increased prevalence of on-television reviewing dedicated to dispensing consumer advice, and of magazine and newspaper features linked only to current releases, or to the Oscar campaign, as if Hollywood’s business was everybody’s business. Critics are no longer respected as individual thinkers, only as adjuncts to advertising. We are not. And we should not be. Criticism needs to be reassessed with this clear understanding: We judge movies because we know movies, and our knowledge is based on learning and experience.

“Truth is the first casualty of war,” runs an old axiom of journalism. In the current war between print and electronic media, in which the Internet has given way to Babel-like chaos, the critical profession has been led toward self-doubt. Individual critics worry about their job security while editors and publishers, afraid of losing advertisers and customers, subject their readers to hype, gossip, and reformulated press releases—but not criticism. Besieged by fear, critics become the victim of commercial design—a conceit whereby the market predetermines content. Journalism illogically becomes oriented to youth, who no longer read.

Commerce, based on fashion and seeming novelty, always prioritizes the idea of newness as a way of favoring the next product and flattering the innocence of eager consumers who, reliably, lack the proverbial skepticism. (“Let the buyer be gullible.”) In this war between traditional journalistic standards and the new acquiescence, the first casualty is expertise.

By offering an alternative deluge of fans’ notes, angry sniping, half-baked impressions, and clubhouse amateurism, the Internet’s free-for-all has helped to further derange the concept of film criticism performed by writers who have studied cinema as well as related forms of history, science, and philosophy. This also differs from the venerable concept of the “gentleman amateur” whose gracious enthusiasms for art forms he himself didn’t practice expressed a valuable civility and sophistication, a means of social uplift. Internet criticism has, instead, unleashed a torrent of deceptive knowledge—a form of idiot savantry—usually based in the unquantifiable “love of movies” (thus corrupting the French academic’s notion of cinephilia).

He continues by deriding the blogosphere:

This is the source of the witty riposte or sarcastic put-down’s being considered the acme of critical language. The Algonquin Round Table’s legacy of high-caliber critical exchange has turned into the viral graffiti on aggregate websites such as Rotten Tomatoes that corral numerous reviews. These sites offer consensus as a substitute for assessment. Rotten Tomatoes readers then post (surprisingly vicious, often bullying) sniper responses to the reviews. These mostly juvenile remarks further shortcut the critical process by jumping straight to the so-called witticism. This isn’t erudition; as film critic Molly Haskell recently observed, “The Internet is democracy’s revenge on democracy.”

Yikes. :

[Pauline] Kael’s cutting remark cuts to the root of criticism’s problem today. Ebert’s way of talking about movies as disconnected from social and moral issues, simply as entertainment, seemed to normalize film discourse—you didn’t have to strive toward it, any Average Joe American could do it. But criticism actually dumbed down. Ebert also made his method a road to celebrity—which destroyed any possibility for a heroic era of film criticism.

At the Movies helped criticism become a way to be famous in the age of TV and exploding media, a dilemma that writer George W. S. Trow distilled in his apercu “The Aesthetic of the Hit”: “To the person growing up in the power of demography, it was clear that history had to do not with the powerful actions of certain men but with the processes of choice and preference.” It was Ebert’s career choice and preference to reduce film discussion to the fumbling of thumbs, pointing out gaffes or withholding “spoilers”—as if a viewer needed only to like or dislike a movie, according to an arbitrary set of specious rules, trends and habits. Not thought. Not feeling. Not experience. Not education. Just reviewing movies the way boys argued about a baseball game.

Don’t misconstrue this as an attack on the still-convalescent Ebert. I wish him nothing but health. But I am trying to clarify where film criticism went bad. Despite Ebert’s recent celebration in both Time magazine and The New York Times as “a great critic,” neither encomium could credit him with a single critical idea, notable literary style or cultural contribution. Each paean resorted to personal, logrolling appreciations. A.O. Scott hit bottom when he corroborated Ebert’s advice, “When writing you should avoid cliché, but on television you should embrace it.” That kind of thinking made Scott’s TV appearances a zero.

While White regularly gets pegged as an intelligent troll, my personal take is that he usually hits the critical nail on the head, even if he comes across as disproportionately strident. On the other hand, his rage is perfectly understandable when you consider that Pauline Kael and Andrew Sarris are allowed to fall into the same categories as most “critics” today.

In other news, my very smart and artistically talented friend, Gene Tanta, about…well, it looks like everything so far.

I’m sitting up in bed, or on the couch, as it were, where I have been trying to sleep off the slew of vodka-and-tonics I downed last night at our reading here in Portland. Shawn Vandor, whose Fire at the end of the rainbow was just , and I read at . Happily I had the chance to meet and fraternize with thethe’s own .

Happily too I have had the chance to experience a temperate spring. In my new adopted home  we have a desert spring, which is an entirely different beast.

we have a desert spring, which is an entirely different beast.  Anyway, it’s been good to see green grass against mud and cherry trees in blossom. All of this reminds me of the wonderful lineage of cold muddy spring poems. There’s ‘Spring and All’

Anyway, it’s been good to see green grass against mud and cherry trees in blossom. All of this reminds me of the wonderful lineage of cold muddy spring poems. There’s ‘Spring and All’

By the road to the contagious hospital

under the surge of the blue

mottled clouds driven from the

northeast—a cold wind. Beyond, the

waste of broad, muddy fields

brown with dried weeds, standing and fallen

patches of standing water

the scattering of tall trees

All along the road the reddish

purplish, forked, upstanding, twiggy

stuff of bushes and small trees

with dead, brown leaves under them

leafless vines—

Lifeless in appearance, sluggish

dazed spring approaches—

They enter the new world naked,

cold, uncertain of all

save that they enter. All about them

the cold, familiar wind—

Now the grass, tomorrow

the stiff curl of wildcarrot leaf

One by one objects are defined—

It quickens: clarity, outline of leaf

But now the stark dignity of

entrance—Still, the profound change

has come upon them: rooted they

grip down and begin to awaken

And then there’s ‘A Cold Spring,’ poem that adds its title to the marquee of Elizabeth Bishop’s 1955 updated North & South. Unfortunately the wintereb is not obliging me, and I cannot find a text of said poem to paste and copy, nor can I manage to get myself out of bed, or off the couch rather, to open the actual book, which is about five feet away from me on one of Shawn’s shelves. Truth be said, I have been consumed with convalescence lately; well, not consumed with it actually, more consumed by the idea of it. But you never know when the time will come.  In fact, several people have been recommending Denton Welch’s to me lately.

In fact, several people have been recommending Denton Welch’s to me lately.

Anyhow, I’m still stuck in this rhyming couplet thing; I can’t tell whether or not it’s a good idea to post my own poems here; especially this one, which I literally just wrote; but nor can I see why this can’t be a forum for, eh, I hate to call it experimentation, or even worse, abusing the reader

or even worse, abusing the reader , but rather using and misusing this poetry stuff in our fraught digital kingdom.

, but rather using and misusing this poetry stuff in our fraught digital kingdom.

Oh yes, back to the couplets. Here are some more. And to further dispel the mystery, I tried to do these while cycling through the vowel-sounds, or vowel-name sounds: ae, ee, aye, oh, you. A little like , I guess, but without the intimidation. So, throat cleared, couplets, voyelles, et le printemps froid:

Here in Portland another day

begins, the sky is the color of spring clay

and in fact it is spring, see

the blossoming tree

outside the window? The sky

is the color of a sigh.

The blossoms show

that flowers too can mimic snow,

and fall, powdering the air they fall through.

The birds seem to have no clue:

can it be said that they pray

for wings they use to flay

the air and so are free?

Their wings must act the key

to a door locked to the sky,

locked no matter how hard humans try

to stick an intrepid toe

through it. Unlike the winterland show

of crystallized precipitation, the blue

provides no backdrop to our dreams, who

dance against open black highway

of orbits at rushing play.

Their flight is galaxy,

not of this world; while the birds are free

to roost and be shy,

and only when they die

do they understand how gravity is foe.

One falls lifeless to the petals––or are they snow?

Armies of gust, the white specks form a crew.

Clouds retreat. The Portland sky is blue.

A.

People talking without speaking

People hearing without listening

People writing songs that voices never share…

-Paul Simon

Music, I regret to say, affects me merely as an arbitrary succession of more or less irritating sounds….

-Vladimir Nabokov

To my wife Anne, without whose silence this book never would have been written.

-Philip K. Dick, dedication page from The Man in the High Castle

B. If you place two or more people in a lobby, they will produce words that string together discussions regarding recent changes in weather. If you put one person in a lobby, he or she will hum a tune no one–not even he or she–knows, atonally and incessantly.

C. This is a cat named Silence. He meows at the door as I write this.

In the Brooklyn apartment where Silence lives, a man came to look at a room for rent. The human tenants explained to the man about daily tasks. “We all contribute,” one said, “when it comes to Silence.”

D. My grandfather tells the story of himself as a boy, talking in class. “Schweig?” the teacher purportedly said, “SCHWEIG!”

E. Somebody in the lobby: “Did you know that ‘Silent’ is what your name means?” Somebody in the lobby: “What are you writing about?”

“You are invisible,” the computer tells me.

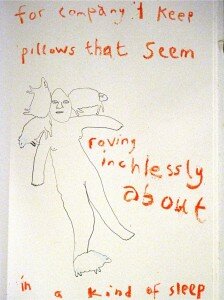

F.

(I have nothing to say

and I am saying it and that is

poetry as I need it.)

G. And there was the time when Charles Wright walked in, sat down and said, “Instead of workshop today, I am going to read from this,” and he held up a book whose cover said, SILENCE. Charles opened the book and started .

Ben Luzzatto’s THE THEORY OF EVERYTHING, ABRIDGED (UDP, 2010) is one of those rare artifacts that transfers its own actual magic—and it is real magic—until the possessed begins to lift a bit toward the sky.

Ugly Duckling Presse has been summed up quite well as “a publishing collective specializing in experimental poetry and new editions of forgotten textual artist, producing lovely, cheeky books by authors you’ve probably never heard of but your grandchildren will likely read in college…a nesting ground for swans of the avant-garde poetry scene.” It’s true that I do feel personally attached to many titles UDP has produced (such as or ). THEORY is the most recent in its Dossier Series, which produced the wonderfully heady though deadly pretentious , and soon will bring out Dottie Lasky’s .

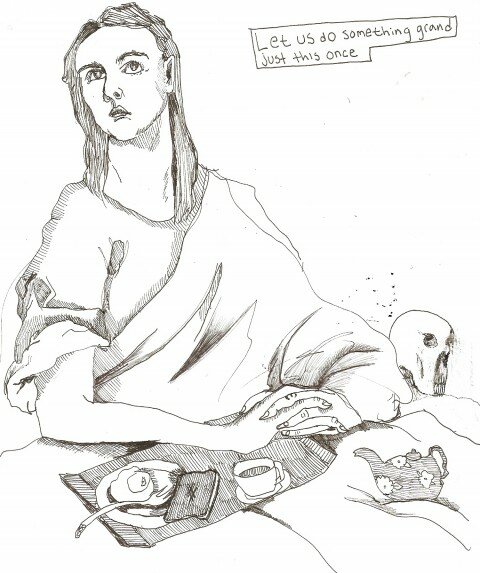

When I first held this particular book though, I do what I do with most books, hold it open it at a distance so I could see the entire cover spread. There was a figure of a someone umbilically attached to something, floating away, or recoiling. An astronaut? A cosmonaut? Where does that road go? You can’t see because of my shaky camera hands, but this is spot glossed over all the silver. This book was printed in Iceland by Oddi, and I haven’t read one word of it as of this point in my engagement and it’s practically trembling in my hands.

THE THEORY OF EVERYTHING, ABRIDGED, is broken into three sections. 1) The Aqueous Humor, 2) From Nonsense to New Sense, and 3) The Theory of Everything, Abridged. Each is a section of conceptual projects narrated by Luzzatto. The first section, The Aqueous Humor, we get what Luzzatto is after in his writing that oscillates from lyrical dreaminess to the more squared off language inherited from the Era of Theory:

“I don’t want to solve the mysteries of the universe, I want to know how I am a part of them…

The more you understand how you are already a part of something, which is the same as understanding how you see something, the more you can separate yourself from it. It is what it was, which already included you, but then it is also something else, which you know does not include you. You have remained together, but you have also become separate.”

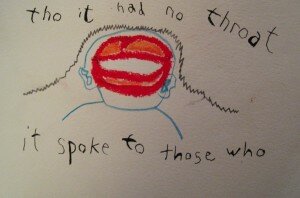

Luzzatto’s ideas as he talks them out seem small compared to the immensity of his ideas as he documents them in photographs that accompany the text . We see images of the Cosmos, an umbrella made of funnels, and in section two, From Nonsense to New Sense, an ontological experiment where the subject ties a bungee cord to a tree (then dashes away from the tree without knowing the length of the rope)

Section three takes up most of the book, and one huge thing I’ve not mentioned yet is that this section involves yet another magickal feat of design, about 80% of the book has a hole through it:

This flip section shows two images of Luzzatto standing on a streer corner. The image below shows through the hole and remains static while the images above narrate a street scene in a city. The animation allows Luzzatto to complete his theory of everything:

“I see two of everything but I am usually not aware of it. A world that comes from me, which is expectation, and a world that comes to me, which is what I do not expect. Most of the time they do not appear to be separate.”

My favorite experiment of Luzzatto’s comes in section two, where the artist makes clouds (!) from helium-inflated urethane cells. I had a dream recently where I was back in my hometown hanging out with my buddy Cori and there was a street that was the actual place where all clouds were made. We were watching them appear out of nothing until they were heavy enough for the wind to lift towards to sky. Amazing. I don’t know what it means (what would Freud say?).

Luzzatto however makes clouds while he is actually awake, and it seems, he is quite good at talking about the whole thing (text following the images):

I assume there is a specific moment/distance at which the cloud disappears as it is rising up into the sky. When it is on its way up, still close to us and clearly a manmade cloud, it is more difficult to see the world that comes from me; it is more difficult to see a cloud that comes from my looking At a specific distance the cloud disappears. It looks like the other clouds in the sky…by making clouds disappear I am able to see how I see.

To see more about UDP, the book, and clouds,

<> <> <>

Stomach

Teeth remain but lips do not.

A flattened pouch filled

With a jackal-headed god’s

Crumbs, a steady and tasteless

Nourishing, until again the

Lips burn, hungry for fowl

In the infinite field of reeds.

Lungs

Tree dismantled. One half

On top the other, losing pink

Quickly. A baboon’s snout

Blows the new air of a god

Inside and during the rise

Twin sponge-roots relearn

To expand, contract, expand.

Intestines

The longest road of the body

Is watched by a hawk-faced god

Who flies the Nile’s length

In two wing-beats, collects

Water in his beak and returns

The river’s still blue coolness

To the driest coil of flesh.

Liver

The usefulness of what’s left

Behind—blessed by the hands of

A god with a human face, wide-eyed

And mindful. Four parts, four winds

Stilled, the kind of silence needed

To end and begin. To make venom

Essential, to warm again the blood.

The function of poetry is to obtain for everybody one kind of success at the limits of the autonomy of will….The limits of the autonomy of the will discovered in poetry are death and the barriers against the access to other consciousnesses….The kind of success which poetry facilitates is called “immortality.”…Immortality is the simultaneity of meaning and being. Immortality can be discussed only in relation to persons….Neither immortality nor persons are conceivable outside of communities.

Strange now to think of you, gone without corsets & eyes, while I walk on the sunny pavement of Greenwich Village.downtown Manhattan, clear winter noon, and I’ve been up all night, talking, talking, reading the Kaddish aloud, listening to Ray Charles blues shout blind on the phonographthe rhythm the rhythm–and your memory in my head three years after—And read Adonais’ last triumphant stanzas aloud—wept, realizing how we suffer—And how Death is that remedy all singers dream of, sing, remember, prophesy as in the Hebrew Anthem, or the Buddhist Book of Answers—and my own imagination of a withered leaf—at dawn—Dreaming back thru life, Your time—and mine accelerating toward Apocalypse,the final moment—the flower burning in the Dayand what comes after,looking back on the mind itself that saw an American citya flash away, and the great dream of Me or China, or you and a phantom Russia, or a crumpled bed that never existed—

A hallmark of Descartes’ view of his splitting of the human being into an extended substance (the body) and a thinking substance (the soul), which are related to one another in a parallel way and do not form an undivided whole. We can observe in philosophy a gradual process of a kind of hypostatization of consciousness: consciousness becomes an independent subject of activity, and indirectly of existence, occuring somehow alongside the body, which is a material structure subject to the laws of nature, to natural determinism. Against the background of such parallelism, combined with simultaneous hypostatization of consciousness, the tendency arises to identify the person with consciousness.

How does one choose which poem should be first in a manuscript? Ben Lerner’s new book, , begins with something resembling a love poem. Joshua Beckman’s latest book, , which I’ve been enjoying lately , uses a kind of apostrophe:

Dear Angry Mob,

Oak Wood Trail is closed to you. We

feel it unnecessary to defend our position,

for we have always thought of ourselves

(and rightly, I venture) as a haven for

those seeking a quiet and solitary

contemplation. We are truly sorry

for the inconvenience….

This is fairly witty–simply to put a short little charmer of a poem out front to ease the reader in–but it also overdetermines my reading of the first few pieces that follow. Then again, where else could such a poem go but at the beginning? I’m at a loss.

Today’s question: How should books begin?

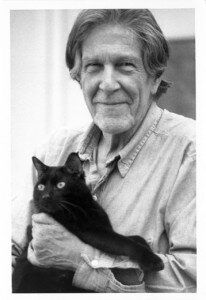

Below are some candid photos I’ve taken of Poetryland’s Personalities.

“One of the marks of our world is perhaps this reversal: we live according to a generalized image-repertoire. Consider the United Sates, where everything is transformed into images: only images exist and are produced and are consumes… Such a reversal necessarily raises the ethical question: not that the image is immoral, irreligious, or diabolic (as some have declared it, upon the advent of the Photograph), but because, when generalized, it completely de-realizes the human world of conflicts and desires, under cover of illustrating it.”

- Mark Strand, Star Black & John Ashbery

- Mark Strand

- John Ashbery & David Lehman

- Harold Bloom

- Timothy Donnelly

- Richard Howard

- Christian Hawkey & Dara Wier

- Christian Hawkey

- James Tate

- Ruth Stone

- Frank O’Hara’s grave

- Lucie Brock-Broido & Tree Swenson

- Paul Mariani

- anonymous poet

- Adam Zagajewski

- John Yau

- John Ashbery (iPhone wallpaper)

- Christopher Ricks

- Linda Gregg

- Hart Crane

- Fanny Howe

- Derek Walcott & Lucie Brock-Broido

“Each photograph is read as the private appearance of its referent: the age of Photography corresponds precisely to the explosion of the private into the public, or rather into the creation of a new social value, which is the publicity of the private: the private is consumes as such, publicly.”

“The Photograph is an extended, loaded evidence — as if it caricatured not the figure of what it represents (quite the converse) but its very existence… The Photograph then becomes a bizarre medium, a new form of hallucination: false on the level of perception, true on the level of time: a temporal hallucination, so to speak, a modest, shared hallucination (on the one hand ‘it is not there,’ on the other ‘but it has indeed been’): a mad image, chafed by reality.”