Mary Karr and Christopher Robinson briefly discuss Tomas Transtromer’s poems “Street Crossing” and “Face to Face.”

October 2010

Ingmar Bergman called Tarkovsky, “the greatest.” It’s hard to argue with Bergman. While Tarkovsky is not a well-enough known director, this is probably just as well because virtually anything popular becomes bastardized. Tarkovsky will probably never be “popular” simply because of the interminable length and oppressive mood of his films.

Tarkovsky created most of his films under the watchful eye of the USSR. The Soviets violently edited (and at other times completely censored) every film he made. His works were considered too politically ambiguous, religiously symbolic, and (of all things) too violent for Soviet tastes. Even the anti-Soviet nationalist Alexander Solzhenitsyn did not approve of Tarkovsky’s violent portrayal of Russia’s past. Because of the repression of the Soviets, Tarkovsky’s films are even more shrouded in poetic mystery. The persistent theme of doubt in all his works would make any sincere Soviet anxious.

Andrei Tarkovsky made an important film called Andrei Rublev, about a doubting monk, Russia’s greatest iconographer. While this seems tedious, it is anything but dull. The film feels very much like Bergman, from whom much of Tarkovsky’s style emerged. Like Bergman’s Seventh Seal, Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev is a slow-paced journey with monks, holy idiots, existential discourse, and symbolic animals.

We modern people forget how extraordinary it is for us to have such extravagant colors in our everyday lives. Even a hundred years ago, this was not the case. Common place things like big red barns were not painted that way to exhibit color, but because red paint was the cheapest at the time.

Color in human creations has been rare until recently. Perhaps humans have changed. It is certainly odd that neither Bible nor the Iliad once speak the color of the sky. The Iliad barely speaks of more color than the “purple gore.” But colors obviously have had significant meaning for people. Visionary colors are important, like the coat of many colors worn by Joseph or the majestic stained glass of Christendom. Aldous Huxley wrote in The Perennial Philosophy that this “visionary experience” is the entire point of self-deprivation which the desert fathers inflicted upon themselves. Asceticism was rewarded by psychonautical adventures.

But for a work about Russia’s most important iconographer, there is precious little color. But a film in black and white representing medieval lifestyles is realistic – much more so than a simple photograph or image. Tarkovsky does not create an image of another time, he creates an icon. You enter that time very readily and watch as the slow and brutal tale unfolds.

The most important moment is at the very end, after all the mindless suffering under the Tatars. It happens quite suddenly, but magically. After watching a film in black and white, you forget you’re watching in black and white. That’s when Tarkovsky makes his move. Suddenly, the film bursts into glorious color. The experience is worth the entire film. It reminds me of reading Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind by Shunryu Suzuki. As you read long, you find words, words, words – and suddenly, when you turn the page, it’s blank with a small sketch of a fly. The jarring experience is nirvana and a radical re-vision of how we normally encounter the world. This same effect is employed (multiple times) in his film Stalker, an excellent and dreary work.

The sort of revelatory encounter presented through all the doubt and angst of Tarkovsky’s films seems almost contradictory, but the essence of Tarkovsky lies in the elusiveness of reality and the religious experience surrounding its ultimate encounter. In his film Stalker he presents the tension between the need to know and the near-impossibility of knowing. The Russian word “stalker” is directly related to the English word “stalker” but without the creepy connotations. I think a better translation might be “follower” — even “disciple.” Stalker begins with sepia-tones and dreariness not unlike Andrei Rublev. After the audience is accustomed to the dull brown tones, suddenly the film bursts into color as the travelers cross a threshold into a dreadful and mysterious territory.

The character named “Stalker” travels with two companions named “Writer” and “Scientist” — one with a poetic sentiment, another with a scientific, and then Stalker himself. The Christic images are evident as he paradoxically leads by following. Rather than heading up the group, he tells them where to go and then follows them. Stalker has an ugly wife and a mutant child named Monkey. He is timid, meek, and apparently a broken man. This journey of faith is almost explicit and incredibly powerful. Often Stalker makes his companions take illogical routes and circumnavigates perfectly obvious paths. The still tension of the unknowable dangers holds the entire film together. One’s sense of time and space are intentionally distorted (intentionally) as sounds remain unheard when we would normally hear them, and rooms become flooded after only a few moments. The distortion of sound lends to the distortion of space and leaves one with a sort of pure existential tension. The same dread drags us through Andrei Rublev but is majestically “resolved” in the dynamic stillness of Rublev’s icons.

The visionary experience is only possible because of suffering not in spite of it. Without the immanent pains of life, there is no transcendence. A doctrine often overlooked in Buddhism is that samsara (suffering) is nirvana. They are one and the same. Because of samsara there is nirvana, because of immanence there is transcendence. Because of becoming, there is being. Tarkovsky must be watched by any self-respecting soul.

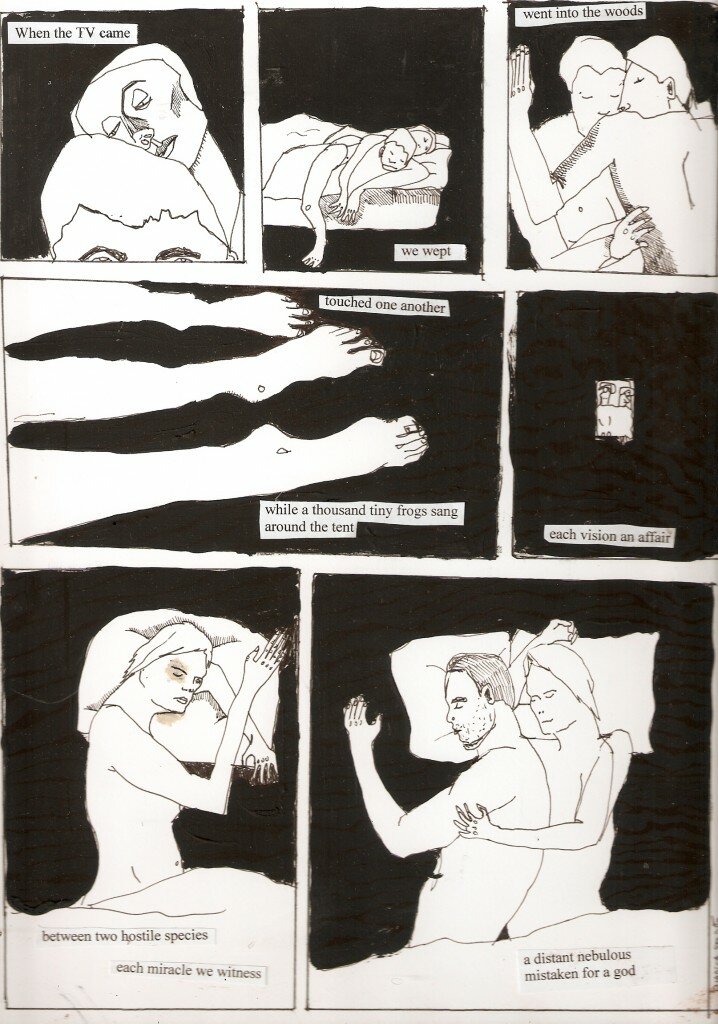

Gene Tanta begins his first book of poems, Unusual Woods, with a 20-page essay that takes shots at T.S. Eliot, Harold Bloom and others. Why does he do this and what is he trying to say?

Surrealism and one of its American progeny, , have never been fully accepted. Their stock has taken a dip in the last few decades. But they are still with us, and they shape our contemporary poetry scene arguably as much as any of the other big guns of modern poetry: Whitman, Imagism, Symbolism.

What Gene Tanta has done in Unusual Woods is take the project of Deep Image poetry, which is to recuperate and shape myths from the images buried in our collective unconscious, and make it local rather than universal. In particular, he is assembling images from various fragments of his Romanian immigrant “area” of the collective unconscious. (The is of course a concept made famous by archetypal criticism and the Deep Image poets. It is the idea that the collective memories of the human race emerge in various forms, such as myths, folklore and the like.)

As I said, Tanta makes poetry out of his Romanian immigrant “area” of the collective unconscious. I say it this way because it is different from any of the following: (a) poetry built on the cultural memory particular only to the Romanian and/or Romanian immigrant experience, (b) the rendering of images and myths only for Romanians, or (c) a poetry that has a particularly Romanian (political) subtext. Instead, Tanta realizes that while his personal and Romanian self is reflected in his work, his American immigrant experience (and his generally human experience) is as well. In fact, the images that make up the 13-line demi-sonnets of Unusual Woods are universally human (while being contemporary). And he is creating “myths” that are universal.

So why does Tanta make such a big deal about his heritage and immigrant identity? In effect, Tanta is doing what any Deep Image poet does (or did)—we all make what we can out of the pieces of the collective unconscious that have been lodged in our particular psyches. A Jungian expects no more or less of anyone. The difference between Tanta and the traditional Deep Image approach is that Tanta foregrounds the particularity and individuality of his own memories and experiences. He knows his cultural biography is the lens through which he experiences and makes sense of his American (and generally human) experience.

This is a level of introspection that most of the Deep Image poets cared only somewhat about. ( is an obvious exception, but he is better understood as the arbiter of .) The others, such as , James Wright, Robert Kelly, are fully invested in the project of finding (somewhat interchangeably) universal and American myths. Also, in as far as they saw themselves as continuing the project of the great modernists, especially the Imagists, these poets were loosely committed to poetry as a universal art form, even if they didn’t take it quite as far as to say a poem exists only as an aesthetic object. These days, our claims about poetry are more modest. We recognize that the role of cultural biography inevitably ties our writing to material, contextual existence.

Recent decades have seen a surge in the “hybrid” poetries of American immigrants. What is particularly interesting about this poetic scene is that Eastern European poets writing as immigrants in English seem, generally, to be keenly aware of the “hybrid” quality of their poetry—they know they have more than one tap root in cultural experience. And yet, they remain ambiguous, or even agnostic, about what the particular components of this hybrid poetics are.

In his essay, however, Tanta offers at least a few concrete explanations. First, he, as an ESL poet, experiences idiomatic language as non-transparent. This shapes his experience of the language, which results in poetry that, like misunderstood idioms, mean different things to different readers: “As a form of linguistic irony, the idiomatic expression itself stands for two things at once, which of these two things the reader comes away with depends on the community with which the reader identifies” (30). This makes our reading of the text contingent and plural.

Another, more significant aspect of Tanta’s cultural biography comes from the mash-up of linguistic elements present within the Romanian tongue—partly Western Latinism, partly mongrelized Turkish and Slavic, Romanian has shaped the way Tanta approaches reality: “My own resistance to binary thinking feels ‘implicit’ and ‘experiential’ . . . and manifests in my practiced refusal to fit into categories of Romanian or American, Poet or Artist, Aesthete or Propagandist” (33). The claim is elemental and common, but it is essential: it’s not simply that different “content” is being inserted into our brains—it’s also that cultural and linguistic features have constructed our consciousness to process the content differently.

Ultimately, though, Tanta wants to have it both ways, and I think he is right. Even though both the form and content of Tanta’s work are particular to his Romanian-immigrant experience, he insists that his poetry is accessible to everyone. His poetry, he says, exists both as aesthetic objects and political propaganda. This is absolutely true about all poetry, not just his own. Inevitably, literary criticism will come to see that literature is always both. Most critics probably know this but have allowed themselves to stray from this obvious fact because the theory wars have created a false dichotomy between cultural and formalist criticism. Tanta brings us back to earth. We all experience texts as both universal and particular—both aesthetic and political:

I will not commit the essentialist error of taking myth of origin . . . only literally or figuratively: both the practical hardships of dislocation and the aesthetic insights that may accompany such cultural shifting go into creating our myths of origin. Cultural identity has multiple and simultaneous histories and motivating factors but this does [not] make it arbitrary. (35)

Later, he writes, “As a poet, I am interested in what the English language can do through how I use it. . . . As a critic, I am faced with the paradox that a poem operates both as an object with aesthetic form and as a process with social content” (36).

Tanta’s essay offers a corrective to the rest of the poetry world. Our readings need to focus on and scrutinize the dialectic between cultural biography and aesthetic form. Tanta claims merely that we need to do so if we are to understand his poetry, but it is not hard to see the wider implications of his argument—this goes for all literary texts. My own sense is that literary criticism has been beating around this bush for a while, even though when we are reading in our right minds most of us would probably concede this fact without difficulty. Many of us are probably already on board with this. Still, there is a notable absence of theory that directly targets the relationship between cultural biography and aesthetics. It’s odd and rather shocking.

Next time I will look at the poems of Unusual Woods, which are gorgeous and demonstrate what Tanta is saying in his essay. It is rewarding to read a poet who is willing explain his poetic approach and is knowledgeable enough to understand it without self-delusion.

Break up into groups, something they love to do now-a-days, and assign the following roles among yourselves: Line and space coach, image and word choice coach, rhythm and syntax coach, and meaning/subtext coach. This last coach will look at the poem in terms of its meaning, try to figure out what the poet’s intentions are for this and that, and edit wherever those intentions seem to be going off.

Now I will model how I might look at a poem when I first receive it and give a brief primer for each of my other coaches.

1. Long Line Poems

Usually, these do not leave much white space, and are either narratives, contain catalogues, lists, enumerations, effect a voice of import (or mock import) and sometimes imitate the gravitas of scripture, but not always. C.K. Williams is known for long lines.

Suffice it to say, these are some of the reasons long lined poems are long lined poems. The free verse of long line poems is usually cadenced, rhapsodic, psalm-like, or prosaic-narrative or epic/mock epic. In free verse terms, its ancestor is the blank verse of Milton, or the rhapsodic, sacred text style of Whitman. Ginsberg’s Howl is written in long lines. Long line poems can be either breathless–a cascade of words and rhythms, or stately.

2. Short Line Poems (Skinny Poems)

In metered verse, these will be poems that employ no more than a couple metrical feet per line (see John Skelton), and in free verse, they usually focus on a single image, or incident, or action. Robert Creeley became famous for the skinny poem. Quickness is one of the purposes of short lines. Another is containment, as if the words–even “is” and “was”–were all precious pearls being squeezed out of a tube.

In a short line poem, each word gains an importance it may not have in longer lines. The poem may appear almost over whelmed by the white space. If the poem goes on too long, it may almost disappear into that white space. Imagine Whitman’s “When Lilacs Last By The Door Yard Bloomed” written out as a Creeley poem (Yikes). Short line poems draw more attention to everything: the line, the space around the line, the words, the syntactical strategy, and so forth. Here’s an example by William Carlos Williams. It is not as thin as his “Locust Tree In Flower,” but it will do for now:

To Waken An Old Lady

Old age is

a flight of small

cheeping birds

skimming

bare trees

above a snow glaze.

Gaining and failing

they are buffeted

by a dark wind–

But what?

On harsh weed stalks

the flock has rested,

the snow

is covered with broken

seedhusks

and the wind tempered

by a shrill

piping of plenty.

3. Medium Line Poems

Medium line poems are not common in early free verse, but gain in frequency once free verse becomes the normative form of writing poems. Why? We tend toward the happy medium in normative structures. The suburbs are neat, and clean, and sensible, and free verse has become neat and clean, and sensible. The language of such medial length free verse is usually measured, understated, nuanced. One of the best poets in this mode is Stephen Dunn. If you study Dunn’s line, you will find, especially in his middle career poems, that he seldom goes over eleven syllables, and that he is a poet of wit, of reason, of a measured and sometimes mildly ironic stance. In his best poems, you get the feeling this is a ruse so as not to ruin the expression of overwhelming feeling by letting it get, well, overwhelming. The medium line poem is saying: “I am measured, I am not flighty, I don’t want to draw the wrong sort of attention to myself.”

The Medium line poem is often a creature of both narrative (long lined) and wisdom (proverbial short line), and its direct ancestor is the sonnet. Dunn does not augment this measured line with false form (putting a poem in tercets, or sextets, or quatrains only because the boxes please someone’s sense of symmetry). You will find this sort of poem proliferating in certain highly thought of literary magazines, but not all.

4. Staggered Line Poems

Those poems that are in or magazines more oriented toward language poetry will use staggered lines, lines that go with Olson’s “Projection By Field” theories. Jorie Graham uses this sort of lineation at times. It tends to announce itself as speculative, experimental, disjointed by desire, Poems that use a varied line–some long, some short, what I will call “undulating” lineation are of two orders: 1. A poet with purpose. 2. A new poet who doesn’t know why his or her lines are long, short, or medium.

So those are the basics. Line coaches, take all this into consideration when you venture towards a class mate’s work.

Image Coach

Imagist poems use image exclusively, or nearly exclusively to either render an object, or to imply a greater meaning (ontology) behind rendering that object, image, etc. You must ask if the poem before you has any images that may not serve the poem. Very often, poets fall in love with an image without considering how it will effect the rest of the poem. If an image sticks out in such a way that the rest of the poem is either dwarfed by it, or out of sync with it note this. We often refuse to kill an image even though it may be killing the poem. Also, be aware of imagery that, if thought about deeply enough, is not really an image:

Black tears of rage pour like rivers

down from her ice blue eyes.

Say these lines ended “To Wake An Old Lady.” It would throw the poem off. It would be out of place. Suddenly this old lady would be a bad actress in a third rate version of media.

Look for cliches. If a personification shows up, ask if it is functional to the poem. If hyperbole rears its head, and the rest of the poem is free of hyperbole, ask if it comes at a critical moment, or is just an alien force within the body of the poem. Word choice is also something to be thought of along these lines. Does the poem suddenly indulge in ten dollar, latinate words when the rest of it uses a simple vocabulary? Is it heavy on adjectives that, rather than modifying and enforcing the power of a noun, are being used as a crutch for nouns that don’t hold up. Think of the sounds of the words.

To that end, here’s a primer on vowel sounds. The highest sound in the English language is the double EE. This is why many depressed writers hate adverbs. Here are the sounds in order of pitch:

– Long E, as in wee

– Long A, as in glade

– Long I as in bide

– Long U as in pew or boo

– Long O as in bone

– Short i as in bit

– short e as in bet

– short A as in bad.

Sounds that are either dipthongs or close:

– oi in boing

– aw as in saw

– ow as in how

– short O as in ah/body

– Om, and short U as in of, butt, luck, mud, muck.

English is not tonal, but it is–just not enough for tones to change meanings (but moods? Definitely!). Here’s a way to see how high and low sounds might function at a primitive level. Baby talk is often more about the sound than the meaning. It is very tonal:

Wee! We say, Wee! yay!

Make fly, sweety pie!

oodles, ooh! my poodle

oh, so soothing!, sit, pet, laugh!

loins burn? Aww!

Ow! How odd!

Uh, Ugly ugums. What muck!

Low u sounds often go with the hardest consonant sounds such as muck. This is not accident. We are tonal creatures. Word coaches, if you see a couple high sounds in a row, or a series of low sounds, or if the uh sound is appearing in places it shouldn’t, or if too many high e sounds are making the poem sound like a ditzy and shallow-pep-rally, note it. If the word choices seem wrong or off, if a simpler word would do, note it.

Note too many passive verbs (is, was, are, were). Note too many verbs made into gerunds. If there is alliteration, is it excessive? If there is an unintentional rhyme, does it hurt the poem?

Syntax and Rhythm Coach

Grammar and syntax control the speed, pacing, and temper of utterance. Grammar, if used with mastery, can create rhythm and timing. So your job is to ask the following: does the poem use complete sentences, and does its punctuation or lack of punctuation add or distract from the poem? If it uses fragments, and run-ons, why? Is the flow confusing? Does the syntax support the rhythm, and is the rhythm organic to the writer’s intentions? If the sentences are paratactic, why? If they are long and go beyond the line, or, if they are full of subsidiary clauses, and added on phrases, does it work, or does it get in the way?

Finally, meaning, and ontology. Here, the coach will determine if the poem is going off its original intentions and why. What is the poet trying to say? This will be the last coach to weigh in, and from this, the discussion of the poem will branch out. I am hoping that the coaches learn something about their own line, word choices, imagery, syntax, rhythm, and meanings while acting as coaches. We shall see. This is division of labor.

Poetry changes when you memorize it. Rather than being a subjective observer viewing an inanimate object, you enter the world of the poem when you memorize. The “departure” from this world and the entrance into an alternative world isn’t science fiction or fantasy. A world is not a physical location, but a way of existing. To indulge in a poem is to taste another world (vocabulary). To memorize a poem is to inhabit another world.

As I have been memorizing Snow’s transcendent translation of Rilke’s Duino Elegies, I have become impressed — no, the poem itself has pressed itself against me. As Rilke says in the first elegy, “And even if one of them pressed me suddenly to his heart, I’d be consumed in his greater existence [Dasein].” Or as Meister Eckhart says, when two beings meet, the lesser one must surrender its being. As man before an Angel, the reader is before the Poem.

I enter the Poem. My everyday “I” is absolved (or dissolved) by suspending my casual vocabulary. My “I” is circumscribed by my idle talk, a vocabulary which is necessarily suspended when engaging a poem.

Memorization originally meant “to write down” but memory existed before the written word, even if only relatively briefly. History as we know it is only possible through written words, even though words suffer a “death” upon leaving the air and being chained to the page. Even if we don’t agree with the totalitarian metaphysics of Plato, we might still say that discourse is violated when translated into letters. The words on the page are not the same as the words we write down.

Due to the perpetual change of our individual selves (temporally, spatially, physically, psychically…), our words never reference the same thing because our words have mutated the moment we speak them: we never mean the same thing as anyone else by a single word — not even our past selves. Written words are static, rigid, and inflexible… yet we are always changing, so our hermeneutical situation is always different, meaning our interpretation of written words is always different. The life of poems is breathed into the written word when the written word is recited.

Memorization, that interminable and exhausting process, places us in the middle of a ‘dead’ vocabulary to which our definitions give life. Spoken word is (hopefully) spontaneous, fluid, and flexible. As Alfred Corn said in his “Department of Records” post, life is change, but change taken to its extreme is death. I would modify this and say that life is a series of infinitesimal deaths. The only way to remain the same is to change. Old habits bind us to a dead version of ourselves — tired, old, and worn out selves.

Memorization forces a radical break in our habitual mind. We are contained by our casual vocabulary, even imprisoned by it. It is nearly impossible to escape it. Memorization breaks the chains of uncritical routine. The “radical break” of memorization is a severance from thoughtless “interpretations” of poetry.

Average everyday people (in most cases) presume the meaning of poetry as a whole (before engaging it!) as 1. Meaningless, or 2. Common sense. The “meaningless” presupposition is closer to the truth; it at least posits the difficulty inherent in interpeting poetry. The “common sense” approach is banal, even obscene. What people consider to be “common sense” is the interpretation of the They-self which is always at odds with individual self-realization. “Common sense,” by asserting knowledge beforehand, conceals the point of departure for any discourse: being-wrong.

Without presuming the possibility of being-wrong, there is no need for investigation, and certainly no need for writing. It is because we are wrong that we write. We also memorize in order to see more clearly, which is one again grounded in our essential being-wrong. In order to become right, we must realize we are wrong, which no “common sense” approach permits.

Even just reading poetry aloud is better than reading silently — silent reading is a relatively new phenomenon. But memorizing engages reading, writing, speaking, hearing, and memory. Memory is one of our most complex powers and is interconnected with our other senses. Memorizing actually brings a poem to life.

Perhaps more importantly, memorizing poetry brings you to life. You empty yourself of yourself and allow a new world to consume you. You emerge into a new light shed on old words.

Herman Melville doesn’t announce the ambition of directly. He kind of sneaks it in. It comes in late and sideways.

At the start the feeling is almost haphazard, and Ismael says, as if in afterthought, “I thought I would sail about a little and see the watery parts of the world.” It’s imagined as a minor event in “the grand programme of Providence,” a little headline lost between “Grand Contested Election for the Presidency of the United States” and “BLOODY BATTLE IN AFFGHANISTAN.” When the ambition is announced, it’s done almost obliquely. It’s done as if the narrator had lingered a little longer than necessary in the library, hoping somebody else would write the book so he wouldn’t have to: “As yet, however,” he says, “the sperm whale, scientific or poetic, lives not complete in any literature … As no better man advances to take this matter in hand, I hereupon offer my own poor endeavors.”

It’s more admission than announcement. It’s a cautious, carefully phrased version of what Walt Whitman wrote, when Whitman, the endless self-promoter, repeatedly claims in poetry and prose, essay and interview that his goal with Leaves of Grass was to put himself and his country, a whole living person and a wide, ever-undulating democracy, into a poem. Melville’s aim is no less ambitious, to put a whole living whale into a book.

Melville isn’t quite so brash to sing of himself, though, or to equate directly himself with the country as a whole. He worries, also, that his ambition will fail, that his picture of the whale will “remain unpainted at the last.” He is always aware he’s always on the verge of the whole thing breaking down, but the ambition is there. Beating underneath. It acts as the will to will it onward, the drive to make it work, a promise to try to do something great, the stakes that are high enough to make it worth while even if the whole thing fails.

Ambition, all by itself, makes the work a thing of value.

There’s so much out there, so much art that doesn’t promise anything. That makes no claim, and no attempt at anything. We’re awash in pop and flutter, blog and clutter. It’s not that little works can’t be great, whether they’re chapbooks or minimalist novellas or graffiti, and it’s not that least important texts of an era, its disposable and mass market texts, can’t actually be really interesting, but there’s no effort, no attempt so great I should yearn for it to succeed.

There are, of course, several very legitimate critiques of such ambition-driven books, of works that weigh this much and have this size. Feminists say phallus. Freudians say ego. Both comments can be kind of true, I think. Both are fair critiques. Megaworks can have the hubris of Manifest Destiny. But ambition, even by itself, even with nothing else sustaining it, can be, for me, a source of value. The scope and scale attempted, even if it fails, means, at least, there’s an attempt at something important, to be something significant.

Put it this way: If I read a single poem and it’s no good, all I can say, I think, is it’s no good. If I read Louis Zukofsky’s “A” and I hate it, at least I can say he was trying to do something important.

I’ve tried and failed to read ‘s 803-page, 40-year poem several times. I don’t know that I’ve even gotten to the middle, though I flipped ahead far enough I know, towards the end, it devolves (?) into musical scores. The first time I picked it up and tried to read I was in a cafe and the waitress, an older lady, asked me if the sequel was B, which basically sums up the work for me.

I mean, I know there are passages in “A” I have found moving and meaningful and riveting —

“Love speaks: ‘in wracked cities there is less action,

Sweet alyssum sometimes is not of time, now

Weep, love’s heir, rhyme not how song’s exaction

Is your distraction — related is equated

How else is love’s distance approximated.”

and,

“‘You write a strange speech.’ ‘This.'”

and,

“– Clear music —

Not calling you names, says Kay,

Poetry is not made of such things,

Music, itch according to its wrongs,

Snapped old catguts of Johan Sebastian,

Society, traduction twice over.”

— and I find it interesting how World War II breaks out in the poem, and I can tell you something at least of why think it’s important —

“Lower limit speech

Upper limit musicNo?”

— but I don’t know that I can argue that it is. I read it, though, and try again because of the ambition, because, even if it fails, “A” seems like it’s trying to do something serious, something important, and because it seems like it’s making, as a work, a promise to be worth while to me. It is or has the air of a grand experiment, of something that can be believed in, invested in, even as it seems to falter and fail.

Even as I struggle with Zukofsky, I find I can believe in him based even on so slight of a thing as ambition. I find myself willing myself to want this experiment to endure, to want to believe, like , to make the comparison between the work and the nation, a comparison Walt Whitman would love, that something “so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure.”

There’s something that’s consecrating about the struggle. There’s something worthwhile about the effort even if it fails.

Which is why, and I know I’ve come here the long way round, . This album he’s released, , is not a bad album. . But it marks, for Stevens, an abandonment of a project that was Whitmanian in its ambition, that was, like Leaves of Grass and Moby-Dick, an ambitious attempt to put a whole country into a work of art. There are not a lot of efforts on this scale, but Stevens, this indie musician who was known, at one point, for wearing wings in concert and signing surprisingly religious songs, started something with his “Fifty States Project.”

With Michigan, in 2003, he started a work that promised to contain a country. A map of a place that is an idea and a feeling, a vision and an angst, our home, the place half known and half remembered and misremembered, mythologized and reinterpreted, the place where we are lost.

In , in 2005, he continued that. The map moved outward and Stevens started to show us the shape of the country he felt, beautiful and strange, scary, sad and mournful. I know, for me, part of my affinity for the work was the way what it described was the home I’ve known, the country I’ve lived in — this was no Whitman ebullience, but a county of , of as suicides, , and this was no Melvillian pursuit of transcendence, but a country of when they’re gone, of but nothing happens — but besides that, ignore that, the work was a promise of scale. This work was claiming to attempt to do everything that can be done with the art form, to be big enough to be important, to try, try to take the whole scope and scale of what we know, all fifty states of our experience, and put it in a series of albums.

Now he’s abandoned it. Two albums, , if you want to , and that’s it for the Fifty States.

It’s like the car broke down on the first day of a road trip.

Stevens is free, of course, to produce what he wants to produce, and if it was a gimmick, as he’s said, then it was a gimmick. But I was willing to trust, when it was clear he was trying to do something worth doing. I was willing to engage, when there was this promise of vistas. Without that effort, that attempt at greatness, that attempt to do what Whitman did or Melville did, to get a whole man, a whole whale, a whole life or country into a work, I don’t know that I’m convinced it’s worth my attention.

I thought Sufjan was trying to do something.

Drawing courtesy of Matt Kirsh, who is, ambitiously, drawing

NOTE: This is the 2nd part in Joe”s series about poetry workshops. The first part can be found here.

Some days in a writing workshop should be like rainy days with a coloring book. In that case, I might let my students just talk and read, or sketch. At arts high, when I thought a student was tired—really tired—I encouraged them to lay down and take a nap.

If I had my way, every writing work shop would have the following:

1. Some plants the students can take care of. The plants could be taken home each week by a different student and cared for until returned when the next class happened.

2. A fish aquarium (I love fish).

3. A workshop dog or cat if no one was allergic. Dogs and cats relieve stress, especially dogs raised to be around sick people (writing has all the outward signs of being sick: you are not involved in heavy physical activity, and you are confined to a room).

4. Two or three computers on which students could put in head phones and watch videos of poetry and music performance, but no more than two or three.

5. Sketch pads, coloring books, crayons, and some water colors.

6. Sculptor’s clay.

I’d have the following books in my class…

Myth related:

–

– Frazier’s

– (Selected and edited by Richard Erdoes and Alfonso Ortiz)

– A standard anthology of world myths

–

–

– A

– A rhyming dictionary

– A good unabridged Webster or Oxford dictionary

– A book of quotations

Art related:

Any art books you could get your hands on: Degas, Picasso, Braque, Jasper Johns, etc., etc.

Poetry Anthologies I’d make available:

– An

–

–

–

– All of Anthologies. They are the most comprehensive collections of folk and alternative/experimental poetry in a general sense that I know.

– (Maria and Jennifer Gillan)

– and (Kenneth Rexroth)

– An anthology of 20th century French verse (I gave mine to Metta Sama because I thought she was a wonderful poet.)

–

– (Neil Astley)

– (Bly, Hillman, & Meade)

– …part anthology, part text, wonderfully sane work

– A Geography of Poets (both and editions)

– An anthology of world poetry, J.D. McClatchy’s comes to mind.

–

–

I am leaving out some good anthologies, but this will give them a start. Hell, I’m doing this by memory. I don’t believe that new means best. New just means new. It’s better for them to see an anthology from 20 years ago, so that they know how few poets truly remain prominent, and so that they read and enjoy poets who have been unjustly forgotten (and ones who have been more than justly forgotten).

Textbooks:

– is a great readable book on the basic types of set forms in poetry

– , Robin Behn and Chase Twichell: lots of prominent poets waxing wise on teaching poetry.

– which one of my students stole. Oh well, I’ll re-buy it. I love when kids steal my books.

– : the entry on the English stanza is a masterpiece of lucidity, and the version with a chapter on free verse is priceless.

I would make each of my students compile an anthology of poems from these anthologies. They can scan it, and print it up. They could form the anthology any way they wanted. They could include friend’s poems (poets certainly do). But it would be no less than a hundred pages, and they’d have to write an introduction for it complete with their own manifesto. It would be interesting to see twenty kids compile one hundred page anthologies. That would be 2000 pages of poetry!

This is my ideal class environment, my dream. They stick creative writing classes just about anywhere—usually anti-septic, drab, “professional” rooms which say: “be creative where no one else ever dared.” I taught a creative writing workshop in a school boiler room in Paterson. It was preferable to most college rooms because, at least, it had cool pipes, and an air of underground danger.

I wish I could make it a rule that every student would create his or her own anthology, and put what they thought were their four best poems in the midst of the poetry gods—just to see how they’d swim. These would be amazing keepsakes. I just might do this.

Anyway, there’s no one stopping someone with money or power from creating such environments. They are not that expensive. There should be such a poetry room in every library and school, and there should be a poet there to guide the students. I’d also have the kids write to lit mags, and see if they could get a deal, and then I’d have two or three hundred literary magazines around. Lit mags love to pretend they want their magazines seen and read, but most of them are financed invalids from universities, and they don’t try hard enough to get the work out there.

I believe environment matters. If it’s really awful, you and the students can bond against it. I had some awful rooms at Arts High—and also at the university. I have one now for my 250, without windows, a ghastly room with hardly any space. But I am not high maintenance. I work with what I got.

In terms of Stevens, I was smitten and terrified by the same thing the people seemed smitten and terrified by in regard to Jesus: “He speaks with authority.” That vatic voice, that voice which flows from a mind and aesthetic impersonality so vast that I can no longer care about sincerity, or insincerity—that is what thrilled me, and I no longer cared what he meant. I was enraptured by what the Irish critic, Dennis Donaghue called “the gibberish of the vulgate.”

Years later, I was able to see some of the mechanisms of thought and feeling in Stevens and I said to myself: “Joe, you can now sound out the idol, and make a more judicious appraisal on your hero. You can sit back and see his faults, and still admire him, albeit, without fear and trembling.” I was wrong.

Being wrong, I turned to Lacan. Why not? If you are wrong, it is best to turn to the French. They have been making correctives almost as long as they have been making wine. So I looked at Stevens in an extra poetic way.

Snob A: The one who, through his supreme talent, must find a rage to order, must ignore the rabble, must be an asshole in the service of heaven.

Snob B: The one who called Gwendolyn Brooks a “nigger,” who enjoyed every drab pleasure of old shoe Harvard; the one who could behave like a lesser Tom Buchanan out of The Great Gatsby: a man so larded with his self-regard, with his cigars, with his trips to Florida, with his success, that he made Hemingway a hero (supposedly Hemingway punched him out); the one who had no trouble living in an icy marriage, and resembled a sort of well done beef Wellington: a cliché snob, a snob fit only for graduate students who have pulled a Kafka and transformed the Beef Wellington of the first half of the 20th century into the couscous of this more “enlightened” age.

Snob C: The one who, like all of us, wants to be a rabbit as king of the ghosts, who wants the cat of death to be a mere bug in the grass; the one who is lofty because he knows at the end of the day, that he, too, must end—and never well. No one ends well. We lie. We die. Lord, have mercy on us!

I took all three of these snobs into consideration, tossed them into the blender, and realized that my aesthetic test for music when I was 13 still applied: if I play a song one hundred times in a row, and, on the last playing, it still has an effect, then it is part of my synaptic hit parade and can never be vanquished. It is the love Shakespeare speaks of when he says “No! It is an ever fixed mark!” This “fixed mark” only exists within instability. It is what the eye or ear or heart seeks and finds while everything else is wobbling. It is a lie, but such a beautiful lie that God (like the gods with Theseus) understands that our lie is wanton in the best sense, and “hath a spirit precluding law.” Such a lie allows us to retrieve what has been lost to the underworld. It is the necessary lie of rising from the dead:

just as my fingers on these keys

Make music, so the self same sounds

On my spirit make a music, too.Music is feeling, then, not sound:

And thus it is that what I feel,

here in this room, desiring you.Thinking of your blue -shadowed silk,

Is music. It is like the strain

Waked in the elders by Susanna.

Helen Vendler made a whole book showing Wallace Stevens was not heatless. Of course he was heartless—all the better, because that meant his liver, and kidneys, and wonderful eyes, and faithfulness (almost) to the tropes of 19th century poetry (the best 19th century American poetry) brought him to a place where only snobbery A and snobbery C mattered. I hope after all these years, I still love Wallace Stevens.

.

The other day, I posted a poem of Pablo Medina’s which I published in my second issue of Black Swan back in 1989. I put the magazine out with money from income tax returns. It was an act of love, an act of madness, and four issues went forth into the world before money prohibited my doing anything out of love.

I look back now and realize I published some good poets and fiction writers who later became well-known (or as well known as you might get in literary circles). It represented a wildly eclectic set of poets, fiction writers, and artists. Some of them, including Creeley, are now dead: my best friend, , Charley Mosler, an unknown jazz poet and pioneer of spoken word, Steward Ross who got angry at me because I cut 14 lines out of one of his poems (it was twenty five lines long), but then used my edited version when he had it published in an anthology, , who ran the Knitting Factory poetry readings for several years.

One of these friends who is still very much alive is . I think Tom is one of the greatest writers of what I call “Wise ass.” “Wise ass” uses the dead pan, absurdism, and just drifting along tone of a comic routine as its chief shaping device. It is post-Lenny Bruce funny, meaning it is not tight and set up like a joke, but wanders over topical terrain, playing with the tropes that run from the silly, and anti-poetic, to the dark humor we might see in certain forms of Eastern European poetry—especially that poetry influenced by dadaism. It is knowing, “hip” in the old style of hip rather than ironic—kind of Steve Martin meets the funnier side of the Beats.

Well, this is an early poem from Obrzut. I think he was only 23 or 24 when he wrote it, and he was a lot prettier than he is now. Some of his newer poetry written by the uglier, older Tom, can be found in . Tom is so deadpan some people take the poem seriously and don’t laugh, and wonder why this guy would talk about his friend eating four pounds of meat a day. Anyway, the poem:

VegetarianismMy friend Anthony used to eat four pounds of meat a day.

Now he doesn’t.

I remember once I was a vegetarian.

Jeff says, “everyone was once a vegetarian.”

So it’s not so special

And besides I never ate four pounds of meat a day

except maybe once and that was kielbasi

Which isn’t exactly the same thing because kielbasi’s different

not like bacon or sausage really.I like eating meat

Allen Ginsberg tells Pollack boys not to eat meat

And the Dalai Lama doesn’t even kill flies

Because he doesn’t want that responsibility.And neither do I,

But there’s all these microbes on the seat of my pants and when I

sit down they’re screaming in pain and dying.

(Now, I know I’m sounding sarcastic and that’s not what I want to do)

I’m just trying to say—

We’re all busy killing things even ourselves

Which isn’t so great but it’s the way it is, the way it was, and

the way it’ll always be.

Someday, I’m going to die and never listen to Elvis ever again.

And that’ll be a shame.

Not especially for anyone else, but I won’t like it so much.

Not that that matters because even God don’t care—or the void or

whatever it is that powers this machine universe—don’t care

what happens to my ass.

And it’s only sad for me because it’s my ass and I like it.

Maybe that’s what the cow said before they smashed him in the

skull in that slaughterhouse

or maybe he didn’t have time and all he could do was think:

“Too bad, too fucking bad.”

As the end of the world came smashing through his eyes—

the way it always does.

Begin with an incidental fact that carries a sense of the ridiculous:

He’s a Dentist Now

My friend Mavis breastfed her children until they were 12.

I mean I thought it was a little quirky, but she was a motherly

type—you know—like the time she made me a quilt of all my favorite characters from Dante’s Inferno?

God I miss her. I thought when they arrested Mavis, it was

excessive. She was nice, always a good word for everyone,

and never a bad, just a good heart—you know what I mean?

The kids are fine—good cheek bones. All that sucking.

Jim, her eldest, went a little crazy for awhile, but don’t we all?

He’s a dentist now, and from what I hear, a really good one.

This ransacks the speaking schtick of Tom, and rambles, but it lacks his sense of voice. Voice cannot be ransacked because true voice, unlike tone, may be inconsistent within its range of indicators. The ability to play a modulating voice against a consistent tone is a deep mystery of poetics—especially of what we might call the conversational poem. Tom does not get outlandish (well he does, but not by creating an extreme situation). To get outlandish would ruin the dead pan. Still, he is absurd, and he uses deadpan and rambling in ways that allow the modulations of consciousness to go just about anywhere without seeming out of bounds.

Of course, if he suddenly gets overtly poetic on us, his poem would fall apart. It is hard to make a lyrical moment out of uber-prosaic lines like “my friend Anthony used to eat four pounds of meat per day.” Tom does what a good poet does—enters his own organic structure of language, and plays his consciousness against that loose structure. It is not the words, or images, but his tone, his timing and rambling that makes his poem work. So here’s your assignment: finish the Mavis poem, and then re-write Tom’s poem, adding poetic imagery. See how it affects the tone or voice? See how far you can take this experiment until the humor of the situation vanishes. You could try writing a pro-meat poem in a voice with a deadly serious, and humorless tone unaware of its own stupidity. Give it a shot.

In , Mathews lets the loose cohesion of his poems suggest profundities that seem unlikely coming from often mundane subjects. His poems are cohesive because of formal structure and theme, but it is a deliberately incoherent kind of cohesion. The effect is delicate and oblique, and it is growing on me.

Mathews likes wandering off the topic (or, really, having no real topic, no subject of discourse), a familiar strategy of and other New York :

For me the identification of trees has always been a puzzle, one not really made easier by consulting the tree book inside my house, where no trees are. I can certainly remember the caramel color of beech leaves in fall, the cropped silhouettes of plan trees along the highway . . . the purpled boughs of Judas trees where no swallow ever perches.

But do swallows ever perch? It seems that every swallow I’ve seen out of its caked nest is part of an ever-changing, bug-eating swarm—a puzzle too mobile to decipher, tumbling and soaring over the cross of a church in Tuscany or Touraine, with pink evening light inside the bell of the air, an image that saddens me when I return to a highway leading north into the night think and empty as caramel custard.

Gorgeous images without a narrative thread to speak of. The speaker digresses smoothly and almost imperceptibly from trees to birds to cake. It’s pleasant and deceptive.

That is part of a prose poem called “Crème Brûlée,” which is not, despite the title, really about custard. Mathews is only teasing you with references to caramel; he’s also thrown in quite a bit about swallows and wine and modern life and the dark side of the psyche:

There are no demons inside you, just your addiction to any puzzle that will addle your contentment, like salt in caramel. You swallow your last glass of wine and return, not unhappily, to the highway.

All the themes have recurred and been recapitulated, but the poem’s point is elusive. Yet, we can’t very easily write off all these wonderfully suggestive images as meaningless, and there does not seem to be any deliberate (and certainly no malicious) trickery. Something’s going on even in the absence of argument and story.

How do the poems gain their highly suggestive character? It is through a highly developed sensitivity to both the literal sensations of the body and the “sensations” of thought. In The New Tourism, Mathews is a conscientious, intelligent hedonist. He is a wine lover, food connoisseur and lover of picturesque landscapes. (If the ability to write breathtaking description is a sign of a skilled poet, he got skills.)

Mathews the hedonist is especially into gastronomic pleasures. In addition to the wine-centric haiku, Halal lamb, and Genoese lunch, the book’s first section, a single poem called “Butter and Eggs: a didactic poem,” is a rather simple litany of about five different ways of making eggs. My favorite part is the scrambled eggs:

When the fat sizzles and smokes

at maximum heat, the skillet withdrawn from the flame,

the eggs are poured into its center and there with a fork or wooden spatula

immediately stirred and turned so that no part of them

stays long in contact wit the scorching surface but the whole

is uninterruptedly mixed and remixed until, attaining a soft solidity,

it can be folded upon itself and promptly flipped onto a plate.

Mathews is just talking about how to cook eggs. He’s paying really close attention to both the delicate things eggs are the delicate process of cooking them. What for? Because it’s frickin’ awesome. Shut up and enjoy the eggs.

And if you don’t appreciate these simple activities, you’ll never appreciate the highly oblique pleasures of Mathews’ complicated, mid-section poems. Whereas in Part I (“Eggs and Butter”) the subject matter itself provided savory delights, in Part II form and structure are the source of titillation. This is evident in “Waiting for Dusk”:

Whoever in the span of his life is confronted by the word “pomegranate”

will experience a mixture of feelings: a longing to see at least once the face

of a Mediterranean god or nymph or faun; the memory of an old silver mirror

decorated with images of varied fruits; a regret at never having known the spell

of a summer picnic ending with the taste of acrid seeds spat over the bridge

parapet . . .. . .

. . . But here now is Simon, with his smiling silly face

from which he extracts tough seeds from his teeth with one awkward forefinger, a spell

of not unsympathetic bad manners that, if truth be told, is a mirrorof our own, perhaps more furtive acts. Then he puts on his mask, made of mirror-

like chromed metal, and I think, why, he could face an kill Medusa! Any weather

has its charm, even the green tempest surrounding her writing snakes that spell

death to the unwary traveler, snakes like a wreath of leeks in a Dutch still life where a pomegranate

cut in two glows idly near the table edge.

It’s a sestina. And it wanders. But that’s what sestinas are supposed to do. The form brings you back to an elusive center, which extends and builds the theme even while the strictures of the form almost inevitably lead to incoherence. (In other words, sestinas tend naturally toward cohesion without coherence.) In Mathews’ sestina, we are washed into meditation by the long lines, complicated sentence structures, striking details (like an “unvarnished table,” below) and the nostalgic, pastoral atmosphere. Profound philosophical gestures lurk near the surface and leap out suddenly but dissipate in the contingencies of life:

. . . Remember the pomegranate

sliced on the unvarnished table, I tell myself, that’s something sharp and real! But the spellof the season and the melancholy hour, sweetened and damped with wine, spell

another revolution of my afternoon regrets, far from Mediterranean . . .

Ultimately, there is a kind of coherence to poems like “Crème Brûlée” and “Waiting for Dusk” that is reached through an almost aesthete-like attentiveness to sensation and thought. And this includes not only literal sensations but human thoughts and discourse. The twists and turns of the mind are like the delicate flavors of breakfast.

new book of poetry, , is a metaphysical meditation on identity through time and the search for the real amidst ghosts, memories, and illusory images. As in the artful illusions of theatre and movies, to which Klein alludes frequently, lighting can change everything in these poems—here people darken or there is an overwhelming bomb-blast of sunlight.

Love and loss seem to be the fundamental elements from which these poems originate. Klein leaves little, if anything, out of his depictions of the essential facets of a certain kind of writer’s life, the trials of a childhood filled with shame and pain, its fair share of neglect, and the realization, even if only for one ghastly instant, that your parents wished you were different from what you are. There is endless questioning of reality and identity; there is the friend with whom you committed the requisite mistake of sex; there is more sex with a true lover; there are the departed, the being haunted, and, always, the daily task and practice—writing—”where you turn the thing like art back into a gift / after it almost kills you” (“Day and paper”).

•

Klein’s poems rarely, if ever, embrace the world with a Romantic’s lyricism. Instead they announce themselves with the consonant staccato of a television’s static, the flatlined cadence that could be attributed to a person touched by post-traumatic stress—the speaker analyzes deeply emotional events without emoting, as in his utterly chronological reportage of his brother’s death in the last couplet of his poem “The twin:” “When he was living, we used to dare each other. / I dare you, he said. I dare you. And then, he died.”

It is also a distinctly post-9/11 psyche that admits the attack on the World Trade Center wasn’t like the movies and it wasn’t real (“2001”). The same psyche is wide-awake to the ongoing economic catastrophe; it intertwines childhood neglect with the enduring and ubiquitous financial strain, “The way [my father] loves me is like the way you remember money—owing / it to someone” (“The ranges”). As much as any conscientious, sensitive person prone to guilt can do, the speaker feels around for someone who we can hold in part responsible for the way we are now; he points to the “governments looking past faces into the fire / of maps on the long table” (“Not light’s version”) and to our fathers littering the ground with “false clues” which they used to confuse us and hide behind (“The ranges”).

The matter-of-fact tone and the all-but-absent-lyricism mark this book as of this time—the post-9/11, recession-beaten, warring, and electronically-oversaturated era. Klein speaks for those of us who are trying to decipher between what is real and what is illusion; these poems depict a speaker who is, like many of us today, trying to stay not only alive, but sentient, all the while bearing witness to the current tides of war, financial collapse, and personal loss.

•

Klein never separates pain from the love that has “made the air visible” (“The movies”). He envisions scenes of his mother’s tortured life (hung out the window by her heels as a girl, beaten by her husbands, writing a book in her mind), and it’s an act of love. Klein attempts to see his mother rather than impose an image of what he wants to see onto the memory of her. In doing so, he acknowledges the variegation of anyone who is real. Klein’s poems open to full bloom when he engages in this act of love, in seeing another person. The poignancy in the poems “The pact” and “My Brother’s Suitcase” is not sentimental. Klein writes in “My brother’s suitcase,”

The suitcase smells like heat and dust and a little bit of the smell that was left in the room

where he died – that horrifyingly real smell of death and alcohol

and something else – left on this suitcase and on the fancy Cole-Haan wallet

he bought himself one Christmas while he had a cab wait.He used to tell that story to people because I think it meant he discovered

that his loneliness was also something that generated a sort of kindness.Even if it was kindness towards himself, he glowed in the back seat of the cab from it.

The matter-of-factness that left earlier poems in the book somewhat brittle, even purposefully inaccessible, becomes a masterfully handled tool of illumination, which Klein uses to look fully at the images of those he loved, those who are now dead. This takes unusual strength and love, as well as a commitment to being a realist. Klein is both a realist about America—we are a country at war and mired in debt—as well as his own reality—he is someone who has suffered and survived the immense losses of his twin brother and his mother. If he is particularly cognizant of the screen images we are all subjected to on a constant basis, it’s because he commits himself to seeing what is real amidst those images: war, loss, and changes brought by time.

This is no movie set: there is the “horrifyingly real smell of death.” And only a son, out of every other being in the world, has the insight to say (in Klein’s level yet devastating voice), “my mother wasn’t finished with her life when she let it go, like a hat in the park” (“The nineties”).

•

Klein’s poems set in motion a deluge of questions: do we change, individually, year to year, afternoon to afternoon? Does humanity change, learn? The answers are never definitive, always dual.

Klein suggests that we as individuals do change through time, as when he ruminates,

My mother’s been dead for so long, that I don’t think she’d remember

who I was even if she did come back – if death lets memory be like

time – or covers the ground with new tracks.

My life’s been moving on the ground of each year she’s been deadand is different than it was when she was coming over for dinner. . .

(“The nineties”).

He asks in the fourth part of the book, “Was America ever the world / we grew up with? Didn’t it stop being that somewhere in the fifties…?” But the poem that follows that one is titled “What war?” and begins, “Some people look into the television into Afghanistan / and say they can’t see anything.” His poems that address death and war beg the question of whether, in fact, humanity ever changes. Klein will not neatly answer any questions for us, but pulls us into the whirlwind of questions about our history and our present situations.

•

Klein questions the reality of the people in his life, referring to them as “the living list of characters in the play about my life as it was being lived” (“You”) and proposes that our world is constantly renewing itself, and that we have no choice but to be changed by the reckless tides of time: “The old fear always follows you into the new life. Who will I be?” (“The movies”).

If the waves of time (which may bring death) settle intermittently, they do so when Klein offers brief interludes of ars poetica. In the poem “You,” Klein delivers a comment about a near death experience that is so modest and unadorned it could be overlooked: “I wondered if it was important / to tell people about it.” But the sentence is an articulation of an experience every writer encounters—questioning if anything written down is important enough to share. Such questioning could, if over-indulged, snuff the entire creative gesture; but it is also a necessary editorial voice to listen to, sparingly. If we did not heed that voice in small doses, we would be left with raw heaps of material, which might satisfy some writers, but not Klein. His poems have been pruned, sheared, shaved, and whittled. He has clearly asked himself the question, is this important to tell? This question becomes more important as he considers the relationship between our present situation and the past.

•

Identities, in Klein’s book, are amorphous, interchangeable, and at times beguiling—he sees his dead twin brother’s distinct swagger in a reflection of himself. However, despite the shapeshifting and misunderstood identities Klein happens upon, there is a steady, consistent speaker throughout these poems who offers his vantage point of the world and of reels of memories. Readers should cling to this consistent ‘I,’ as anyone would cling to a steady form of consciousness in a world that alters or altogether disappears; like money, people and time are “always falling from our hands” (“The pact”). The ‘I’ is the rope Klein throws to us as we walk hesitatingly, jerkily, through his poems; the ‘I’ becomes an eye that lets us “see in the dark,” buoys us as we float on the “the scotch wave of light” (“A saver”).

•

The experience of reading these poems is not an easy, nor a rapturous one. We experience at times “the depressive’s only language: a dead language / the depressive’s temporary cure: the shine on a wave.” If, however, there is rapture in these poems, it comes from the difficulty of them. Klein’s poetry is, then, in keeping with Rilke’s advice to a young poet when he observes, “Most people have (with the help of conventions) turned their solutions toward what is easy and toward the easiest side of the easy; but it is clear that we must trust in what is difficult; everything alive trusts in it….”

Interviewer: The Paris Review has one quintessential question, which it has asked everybody from William Faulkner to Ernest Hemingway. What is the implement that you write with?

: I use my toenails actually—collect them, hammer them down, mold them into shape …

William Styron didn’t write in notebooks. He tried notebooks, but they didn’t work for him. They do work for Paul Auster, though, so he writes in notebooks. He likes the ones with gridded lines, which he calls “quadrille lines — the little squares.” When Auster’s done with the notebooks he types everything up. He has a typewriter he bought in 1974.

What is that supposed to tell us? What does this reveal about Styron? What do we know or understand about Auster that we didn’t before?

has been interviewing writers since 1953, and for more than five decades they’ve been asking this question about implements, about the actual, tactile things writers use to write. The question is, why? What is it we actually want to get at with this “quintessential” question? What are we supposed to know when we know the answer?

Hemingway would sharpen all his pencils — seven No. 2s — before he started writing. This is what he said, anyway. He said this in the Paris Review interview in 1954, which is about half way between his Nobel Prize and his suicide, after he’d stopped publishing books, and in the interview, when he says it, it sounds like it could be a joke, or maybe a self-made myth, a little mystification.

I don’t even have any pencils in my house, much less seven, and the last time I can remember writing with a No. 2 was when I took the SATs and filled in those little bubbles. If I had them, though, I’d take them out now and sharpen them all and lay them out in a row. And then what? What would I know?

It’s possible, I realize, that I’m thinking about this wrong. It’s possible the question isn’t probing at anything deeper. Maybe we really are just earnestly interested in typewriters and notebooks, pens, paper and blank computer screens. Maybe it’s just interesting to know. It’s framed, though, as an important question. The question seems to me to be about more than it’s about. It’s like a fetish. We seem to think there’s a secret here, a revelation to be revealed, a mystical, magical something we want to learn.

I’ve been thinking about this question because I’ve been reading all the times it was asked in those old Paris Review . They’re , as of a few weeks ago, which means they can be more easily looked at as a group. I have often liked particular interviewers and found them interesting and useful. As a whole, though, as a corpus, there’s something disturbing there.

There’s something very canonistic about them. Something … institutional. By which I mean, literature is presented in a weird way; its mystified, presented as if authorized, and made into something sort of magisterial.

Maybe its the problem with the interview as an art form: the condition of the interview is that the subject be worth interviewing, be an institution, be recognized. The author, in the interview form, can only be approached respectfully. The author is given, granted, this assumed position of authority to speak with finality, an authority that’s something like God’s. The author-god gets the final word, gets to answer the question about meaning in final way. That’s the ground of the form, the assumption of it. If the author-god protests against that assumption not least because it diminishes the work itself, marks he work as insufficient to itself, as something that needs this supplemental pronouncement, if the author-god protests as Faulkner does in his interview, saying “The artist is of no importance,” and “If I had not existed, someone else would have written me,” the protest is feeble in the face of the force of the assumption. Even as he says it it’s undermined by the fact he says it as Author. Anything he says is said from this position of having the right to the last say, and of course even if the author refuses to answer, that only heightens the mystery and makes us surer, because we were refused, that the author has the secret, the ultimate answer.

It’s not an accident, I don’t think, that the Paris Review interviewed its first author in 1953, inaugurating its “” in a series that developed and popularized a form of discourse giving authors ultimate authority to pronounce on (and foreclose) the meanings of their texts. This was the same year and the same place that Roland Barthes published his first book, , which looked at the arbitrariness and constructedness of language, beginning a career that developed and popularized the school of thought that pronounced . It’s literary equivalent of the , when Abraham dwelt in Cannon and Lot went down to the cities on the plain. The interview form might well be thought of as the counter movement to the movement that killed the author, though the effort wasn’t one to keep the author alive as much as to enact a kind of deification. But, just as the death works to liberate the work, to open it up to criticism and to thinking, the enshrinment of the author acts to canonize literature, it lock it up in an orthodoxy.

This can be seen in , which happened in America at the same time: The great works of Western literature were bound in black and peddled from door to door, 54 forbidding volumes of works you were supposed to read.

They were, with this mystification, authorized, and elevated, raised to an aspirational level where they would be safe from reading. Instead of literature as a loud conversation, this was literature as a cathedral. It was conceived of as a class marker, a taste marker, as something genteel the middle classes could work towards and aspire too.

Don’t misunderstand, this isn’t just an attack on the great books. Or even The Great Books capitalized as they so often are. I went to the college I went to so I could read the canon, and I have read and value having read Virgil and Dante and Milton, Chaucer, Cervantes, Whitman and Hawthorne and Melville. But reading, for me, only makes sense as a struggle. Reading is a fighting-with. It isn’t and cannot be an act of reverence, because to read I must engage, and engagement implies a kind of conflict, a struggle. More than one conservative old prof. told me I was doing it wrong, but for me the great books is a big street brawl.

I guess this is what bothers me about the quintessential question they ask at the Paris Review. Writing is mystified with this question. The objects are presented like they’re magic, and they become objects to fetishize.

Joseph Heller wrote stuff down on 3×5 cards he kept in his wallet, which he called a “billfold” in ’74. Gore Vidal writes fiction on yellow legal pads, but essays and plays on a typewriter. John Updike had a typewriter too and . Gay Talese wrote outlines in different colors of ink on the shirt boards he got when his clothes come back from the dry cleaners.

What if none of this information actually acts to reveal anything? What if what it does is conceal? I think the question could offer a chance to think seriously about the materiality of writing — Don DeLillo does this, a little, with his answer, as does Jonathan Letham — but most of the time the question and these answers act to do the opposite, to cover up the complications and contingencies, to mask writing and make it mystical. It could be a good question. It could be followed up with questions that open it up: What difference does it make that you write the way you write? How does how you write shape your writing? Do the tools you use naturalize the text for you, make it kind of invisible, or does it heighten your awareness of the text as text and make more apparent the texture of the words?

It could, I think, really open some questions about writing up to thinking, but it doesn’t. Instead we end up with pin-up .

It’s like seeing a math equation with all the work erased. This is the example Roland Barthes uses, talking about Einstein in popular culture and how a fetish developed about his brain. Culturally, Barthes says, we began to talk about his brain as a machine, but not to actually reveal the thought and explain how the thoughts were thought, but to veil it in the mystery of genius. He says,

“Popular imagery faithfully expresses this: photographs of Einstein show him standing next to a blackboard covered with mathematical signs of obvious complexity, but cartoons of Einstein (the sign that he has become legend) show him chalk still in hand, and having just writing on the empty blackboard, as if without preparation, the magic formula of the world.”

If they asked Einstein, at the Paris Review, “what do you write with? what is the implement you use?” he would have said chalk. He would have said, “I write on a blackboard.”

But the answer to the quintessential question wouldn’t tell us more about his writing, but less. It wouldn’t reveal, but conceal. It would enable us to make a fetish out of his chalk like we make a fetish out of his brain, and we could put his chalk next to Heller’s note cards and Hemingway’s pencils, but we wouldn’t have a better critical understanding of the formula of the world, or how it was different because it was written with chalk then it would have been if it was written in red ink, or in a margin, or on a note card on a rooftop at dawn.

I really think it could be a good question. It could do what Charles Bernstein said he wanted to do in , when he said he wanted to “ , the stuff, of writing, in order, in turn, to base a discussion of writing on its medium rather than on preconceived literary ideas of subject matter or form,” a way to make the materiality of writing visible instead of repressing it and “making the language as transparent as possible.”

What we end up with, though, is a fetish. Another way to not think about writing. The quintessential question is quintessential as an “alternative to criticism,” which is also, I think, an alternative to thinking, and isn’t just an alternative, but actually a defense against it

I was looking at an old copy of the Black Swan Review, which I founded and published many years ago (1989), and came across a poem by the Cuban American poet/novelist, Pablo Medina. It’s short, written a bit in one of the three types of lyricism that were prevalent back then (call it minimalist deep imagism). In deep imagism, you expect certain tag words such as wind, dark, bones, shadow, stones, sky, etc. This is also true of Spanish surrealism, a form of surrealism as influential on deep imagists (and later, Larry Levis) as French surrealism and dada are on the New York school.

At any rate, in this poem, we have wind, darkness, snow, bones, shadow…pretty much all the basic ingredients for minimalist deep imagism ( or Spanish surreal lyricism) with the exception of angels, ashes, and blood. Let’s have a look-see:

Cadwalader Park, Late Fall

Pablo MedinaThe strollers hunch

against the wind, call to their children

from lengthening the shadows.The parents turn to each other.

More lines in the face,

more of the tinge of age.When the man wants a kiss

his eyes open to his mate’s bones,

slow of speech, eyebrows frail as horizons.The harvest is done.

The year darkens into snow.

It’s sort of a moody haiku on steroids. It uses some of the mechanisms of haiku: reference to the seasons, above all, short, paratactic sentences. It is neatly packaged in a series of tercet, concluded with a couplet. The trajectory of the poem goes from a long shot of strollers in a park, to a close up of lined faces tinged with age, and then some odd tercet in which a man eye’s open to his mate’s bones, and someone (the mate, or the man, or the bones) is “slow of speech, with eyebrows frail as horizons. It is scene painting, and mood painting. Now here’s the sampling game. First, make a poem in which you use Medina’s three tercet and a concluding couplet structure, but mess with his words, and make the sentences a series of directives, with a concluding couplet of questions:

Hunch against the wind.

Call to the shadows

of lengthening children.

See how they grow

tinged with age in the

day’s last light.

Know they are the bones

of a kiss. Open them slowly,

weather them frail.

Are they the horizons of your eye brows?

Are they the year darkening into snow?

This ransacking is far more surreal. Instead of the shadows lengthening, the children lengthen. To call children the “bones of a kiss” is not so inaccurate if you reduce their life to bones, and the sex that leads to their life to a kiss. In point of fact, it’s far more original—kind of resembles Wordsworth’s contention that “the son is father to the man.” The poem is as gloomy as Medina’s, but it does not so much paint a scene as turn Cadwalader park, late fall into a strange sort of surrealist hymn to mortality, to transience, a theme latent in the initial poem. Here, the children become the main focus. The voice of the poem is issuing orders: Hunch, call, see, know.

I have not used a single line of Pablo’s poem. I have used words, images, re-constructed them. I could call the poem, “A Directive.” Medina never said the children were the bones of a kiss. He never said they were the year darkening into snow. We took the structure, and, in a sense, the mood painted by minimalist words. We took the parataxis, and made it more pronounced, but this is a wholly distinct poem. The lineation is far less regular, with the couplets being far longer lines.

Assignment: Find a poem and do the same. Cop its structure, and even some of its key words, but change the type of sentences, and fool with the images. Good luck.

This month Metro Rhythm is proud to present five outstanding poets: Meghan O’Rourke, Eleanor Lerman, Sarah V. Schweig, Zachary Pace and Jay Deshpande. The reading will be held at Blue Angel Wines in Williamsburg, Brooklyn.

In a recent blog post, and takes George Philip, president of SUNY-Albany, to task for axing the French, Italian, classics, Russian, and theater programs. Fish claims

it is the job of presidents and chancellors to proclaim the value of liberal arts education loudly and often and at least try to make the powers that be understand what is being lost when traditions of culture and art that have been vital for hundreds and even thousands of years disappear from the academic scene.