There’s been a bit of back and forth about questions of translatability ( and ), and I thought it was worth some observations.

I have mentioned this before on the blog, but for those who do not know, I teach upper level ESL to students who plan on entering graduate school in North America. It’s basically a college writing class, but the ESL aspect creates interesting dilemmas for me as a teacher. For example, I’m consistently torn between allowing students the comfort of pulling out their electronic dictionaries and forcing them to live in the uncomfortable space between languages. If I allow dictionaries, I will essentially handicap (or allowing them to handicap) their future English skills. They will forever be tying English words to words or phrases in their native language. As a result, they will never be fully fluent in English (at least not in the same way as a native speaker is fluent–which is often what most of my students desire). If, however, I force them to use context, word roots, and experience to understand words, eventually they will understand English words in an English sense. Perhaps an end-run around this dilemma is letting them use an English dictionary, forcing them to associate English definitions with English words. Unfortunately, students often come upon words in the English definition that they don’t understand, so we’re back at the same dilemma again. Spare the rod, spoil the child, anybody?

Typically, by the time students get to a level or two below my class, electronic dictionaries are forbidden in the classroom. It’s much harder, though, to break them of the habit of composing whole sentences in their own language and translating them, an attempt which is doomed from the start. I get lots of grumble and pout when I tell them to start thinking about their papers in English. I feel a bit like a parent coaxing their child to stand up to a bully. And in many ways, a new language is a bully. I always tell my students that learning a new language is not really learning a new way to communicate, but a new way to think. When working in English, you have to know how to work within or manipulate the categories and expectations of English–something we native speakers do without realizing.

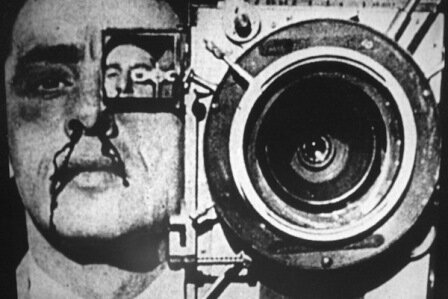

Which brings me back to the blog posts I mentioned in the beginning. As Geoffrey K. Pullum points out at Language Log, doesn’t really mean there is no translation, it just means there is no one-word equivalent in English. This is the difficulty with translating poetry and why it is often such a fruitful angle to approach questions of poetics. What makes the poetics of a particular work tick? By poetics, I don’t just mean poetry, I mean all art forms (I tend to think of “poetics” as an arch-art form). Dziga Vertov, for example, thought that film was a new international language, a sort of visual . In his avant-garde film, , Vertov boldly declares in the first title cards:

The film Man with a Movie Camera represents

AN EXPERIMENTATION IN THE CINEMATIC TRANSMISSION

Of visual phenomena

WITHOUT THE USE OF INTERTITLES

(a film without intertitles)

WITHOUT THE HELP OF A SCRIPT

(a film without script)

WITHOUT THE HELP OF A THEATRE

(a film without actors, without sets, etc.)

This new experimentation work by Kino-Eye is directed towards the creation of an authentically international absolute language of cinema – ABSOLUTE KINOGRAPHY – on the basis of its complete separation from the language of theatre and literature.

Vertov’s ambition is palpable in the film. Each cut is gravid with meaning. Not only would film be the first international language, it would be the language of the revolution (according to Eisenstein). Many of us still think that film is an international language. In many ways, it is true. It certainly speaks across many cultures, but as McLuhan points out in Gutenberg Galaxy, film is the product of a literary mind. The conventions of film (at least as Vertov sees them) are the conventions of visual print culture. That is, we read films much in the same way we read books.

McLuhan describes the experience of aid workers (in the 1960s, I believe) showing hygiene films to people from what McLuhan identifies as aural-tactile culture (that is, lacking the thought structures that are inherited from print culture). It’s a bit too long to quote here (), but the basic gist is this:

“Literacy gives people the power to focus a little way in front of the image so that we are able to take in the picture in a whole glance. Non-literate people have no such acquired habit and do not look at objects in our way.”

Later McLuhan quotes John Wilson:

“Film is, as produced in the West, a highly conventionalized piece of symbolism although it looks very real. For instance, we found that if you were telling a story about two men to an African audience and one had finished his business and he went off the edge of the screen, the audience wanted to know what had happened to him; they didn’t accept that this was just the end of him and that he was of no more interest in the story. They wanted to know what happened to the fellow, and we had to write stories that way, putting in a lot of information that wasn’t necessary to us. We had to follow him along the street until he took a natural turn–he mustn’t walk off the side of the screen, but must walk down the street and make a natural turn….Panning shots were very confusing because the audience didn’t realize what was happening. They thought the items and details inside the picture were literally moving….the convention was not accepted.”

The point of sharing all this (aside from the point that it’s generally fascinating) is to show that even images, which we often consider somewhat universal, often require certain conventions of thought. So even there, the poetics of an art form are mitigated by “translation,” which, quite literally, must translate it from one form of thought to another.

I do believe fruitful translation can and does happen, but we must be aware of the “extra layer(s)” of intent that exists over top a piece. I want to focus more on what we as poets (and poeticists) can learn from and through translation when I review the new translations of Horace’s Odes (edited by J.D. McClatchy), so the rest of this discussion will be postponed until then.

Good post.

Our students — German freshman — are only allowed to use monolingual dictionaries in class. I also pretend to know less German than I do, so when a student “doesn’t know the word for it in English,” where they want to give out the German word and get the English equivalent, they’re forced to give me a discursive English explanation of the idea they want with the word.

Even that sometimes doesn’t work, e.g., “what’s the one word for when you’re feeling happy after a long time being sad, but not just you, the whole group, and it’s a feeling of relief, and like something new is starting?”

I read, recently, about a couple that translates Russian novels (new editions of Dostoyevsky, etc.) and she’s a native Russian speaker, he’s native English, and they break the translation down into a two part job. I wonder if there isn’t something to that, in that they’re each working in the one language, and only going half way across the bridge.

When working in English, you have to know how to work within or manipulate the categories and expectations of English–something we native speakers do without realizing.

To the above: Yes! That’s so true. In 2008 I spent the summer in a French-speaking part of West Africa. When I got there I was already moderately fluent (and overly proud of it), but that was just from book study and practice. I’d never been to an actual francophone country before. I quickly learned that you have to have a pretty good idea of what the person you’re conversing with could say next in order to be prepared to reply. That blew my mind. Fluency in another language requires an entirely new mindset; you can’t think about it.

I knew I had fairly arrived when, near the end of my trip, a friend asked me a question in English and I answered in French without realizing until a few seconds later. I was so excited!

this is a very interesting story. i always like to ask my students when they start dreaming in english. you know it’s starting to seep in at that point–for better or for worse, their brain wiring is never linguistically the same.

Hey Micah, During my search for new American poetry, I came across this blog. Very interesting contributions. I’m surpised to learn that you finished your MFA at the Hunter College. in the Hunter College have completed your master. . I have studied art in Hamburg and is currently studying (a PhD) in JVE Maastricht NL. Currently I work on a film project, an artistic film. It is a kind of political thriller within thematise the morality and culture ideals of Western civilization. After I read at your posts about Vertov film Revolutions Language , very interesting , I´ll like to send you the script of my project , to hear your interesting opinion about it what finaly could be very constructive for me.

Best regards a

hi bregu–i sent you an email. thanks for the request.