The two women in the adjacent garden, draped with thick woolens, braids hanging down from both sides of the skull, hitched together with a string between their shoulder blades. They pause their spade, their hoe, or their small hand trowel and admire a mating pair of Hoopoe birds, audaciously mohawked with tangerine and flashing zebra stripes, as the birds drill their beaks into the sheaves of a wooden shed. The garden stops. The women stop. I stop, though I don’t know if I was moving at all. And aside from the birds the only things that seem to move are the clouds, scraping their bottoms against jagged Himalayan teeth. For a moment it looks as if we are all characters playing out a scene in one great, gaping jaw of rock and sand. It looks like the world is trying to eat the sky.

The two women in the adjacent garden, draped with thick woolens, braids hanging down from both sides of the skull, hitched together with a string between their shoulder blades. They pause their spade, their hoe, or their small hand trowel and admire a mating pair of Hoopoe birds, audaciously mohawked with tangerine and flashing zebra stripes, as the birds drill their beaks into the sheaves of a wooden shed. The garden stops. The women stop. I stop, though I don’t know if I was moving at all. And aside from the birds the only things that seem to move are the clouds, scraping their bottoms against jagged Himalayan teeth. For a moment it looks as if we are all characters playing out a scene in one great, gaping jaw of rock and sand. It looks like the world is trying to eat the sky.

___

At the airport there is a sign advising the steps one should take to avoid Acute Mountain Sickness. I know the steps: rest on day one and maybe on day two, as well; drink plenty of water; avoid strenuous activity; ascend to further altitudes with great caution and only after acclimatizing. I  have landed in Leh, at 3500 meters, it’s a city that sits between dusty, ragged mountains which, in turn, sit in the lap of massive summits capped with snow. The air is short on oxygen. Should one feel dizzy, or get a headache, one should consider ceasing all activity. Should one become disoriented, confused, develop a dry cough which produces a foamy pink sputum, one should immediately seek medical attention. All of this can develop gradually or with unpredictable speed. Often the more insidious symptoms exhibit themselves at night when one’s breathing is less deep, so avoid sedatives, which is what one might naturally reach for because one also will likely experience disruptions in one’s sleep.

have landed in Leh, at 3500 meters, it’s a city that sits between dusty, ragged mountains which, in turn, sit in the lap of massive summits capped with snow. The air is short on oxygen. Should one feel dizzy, or get a headache, one should consider ceasing all activity. Should one become disoriented, confused, develop a dry cough which produces a foamy pink sputum, one should immediately seek medical attention. All of this can develop gradually or with unpredictable speed. Often the more insidious symptoms exhibit themselves at night when one’s breathing is less deep, so avoid sedatives, which is what one might naturally reach for because one also will likely experience disruptions in one’s sleep.

The first night I am sure that my breath stops every time I doze off. Also, I am dizzy. My hands get tingling cold and I’m certain that they are turning blue.

The following evening I develop a pain in my chest, behind my sternum. It could be indigestion from the chili sauce that I added to my Thentuk soup at lunch. It could also be a definite sign that my throat is closing, that my lungs and diaphragm are infuriated by the lack of oxygen in the atmosphere. Somehow I sleep. I wake the next morning and cough up pink. I am sure I am dying. The nice man at the Hayan Himalaya tour agency did advise me to see a doctor when I told him about this dull, clenching ache. He was probably right. I have got to find a hospital. I should have found one last night. Then I drowsily remember that I chewed several Pepto Bismol tablets the night before in a desperate attempt to alleviate the pain. Three Advil later in the day make the pain disappear. I have not died. Also, once I stop the altitude medicine Diamox, the dizziness and hand tingling subside.

By the third evening, I accept that I most likely will not die from AMS, but decide that I am not going to tempt fate. I avoid seeing far-flung beauties like the quaint Ladakhi villages of the isolated Nubra Valley or Pagong Tso—a lake surrounded by salt flats said to inspire near-tears in those who witness it by the light of a full moon, which it almost happens to be during my trip. They are too high. My bravery only functions at sea level. I do not want to die, alone, in a cold bed in the Himalaya.

___

I am lonely. The room at my guest house is huge and empty except for a low table, a plastic lawn chair, and two twin mattresses pushed together for a bed. I only sleep on one side of the bed, having left my partner David behind in New York. After nearly four years, and despite thinking that I love solitude above all else, it seems that I’ve lost the ability to comfortably sleep alone. The power goes out every hour or so and this can last for minutes or hours. I buy a bootleg of Seven Years In Tibet because in the black silence I do not know what to do with myself without television or the internet or a light by which to read a book. I waste the charge on my laptop down every night, watching Brad Pitt abandon his life in Austria for a dream that turns nightmare that turns dream. At least this is what I think happens. I never make it through the film, but only see it in waking snippets, usually when the score swells and a momentous event has transpired. I know enough to know that Brad Pitt’s German accent bothers me, and that one should not lie about injuries, physical or otherwise, when high in the mountains. And that the Dalai Lama, as a child, liked music boxes, as children often do.

I am lonely. The room at my guest house is huge and empty except for a low table, a plastic lawn chair, and two twin mattresses pushed together for a bed. I only sleep on one side of the bed, having left my partner David behind in New York. After nearly four years, and despite thinking that I love solitude above all else, it seems that I’ve lost the ability to comfortably sleep alone. The power goes out every hour or so and this can last for minutes or hours. I buy a bootleg of Seven Years In Tibet because in the black silence I do not know what to do with myself without television or the internet or a light by which to read a book. I waste the charge on my laptop down every night, watching Brad Pitt abandon his life in Austria for a dream that turns nightmare that turns dream. At least this is what I think happens. I never make it through the film, but only see it in waking snippets, usually when the score swells and a momentous event has transpired. I know enough to know that Brad Pitt’s German accent bothers me, and that one should not lie about injuries, physical or otherwise, when high in the mountains. And that the Dalai Lama, as a child, liked music boxes, as children often do.

___

No, I am not Buddhist.

Then why are you visiting all of these monasteries?

Because I chant.

What do you say when you chant?

Om mani padme hum. Nam myoho rengekyo.

Those are Buddhist.

I know.

I discover a small, modern temple at the top of a dun colored hill outside of town, adjacent a monumental stupa built by Japanese Buddhists. I am telling two British girls who have invited me to eat with them about the place when the inevitable line of questioning comes: are you Buddhist? It’s hard for me to say what I am, where I stand, other than somewhere between a vehement atheist and an agnostic in search of a source and a meaning. I need more definite answers.

It’s hard for me to say what I am, where I stand, other than somewhere between a vehement atheist and an agnostic in search of a source and a meaning. I need more definite answers.

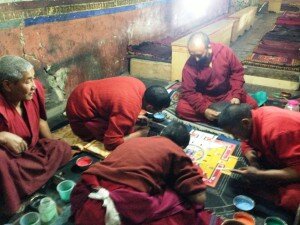

I hike back up the steep, switchback stairs the following day. I’m sure this hike is part of the process, as these temples always seem to be atop crags and rocky spires. I stare at the placid face of a gilded Maitreya Buddha. Om mani padme hum. Nam myoho renge kyo. I freely switch between the chants—Tibetan then Japanese and back—appreciating their similar syllabic cadence, however, I’m unsure if there are proscriptions against this sort of freewheeling. I switch between those Buddhist chants and Hail Marys because I know of no other way to approach holiness or the sacred. I chant until my jaw hurts, until my face aches. And when I stop, I notice the way my cheeks seem to vibrate, the way my head feels syrupy and light. I notice the comparative stillness in the rest of my body.

This must be what they mean by serenity.

And Indian family takes several photos of me, with flash, as I hold my eyes shut and clutch the string of wooden Mala beads.

Say the mantra.

Say it again.

___

I hang up the phone with David. I’ve been choking back tears. It has been hard to talk. I feel as though I’ve done something I shouldn’t when in truth I’ve done nothing wrong. The only thing I’ve done is decided to travel by myself, far from home. I’m regretting the choice. I hate that I can’t truthfully say that I am in awe every day, that I’m inspired every second. It is hard to be here, to be present, to take it all in—these huge mountains and churning turquoise Indus and the wide swaths of stars at night—the way everything feels so static and shaking at the same time.

I walk up the hill from the phone booth and see an advertisement for a company that drives its customers to Khardung La—the highest motorable road in the world—and then lets them ride mountain bikes down, back into town. It sounds awesome, and doesn’t require long stays at high altitudes. But I’m sure that this is something I should do with David. For a moment I forbid myself to have any fun. That moment lasts a few days. I restrict myself to the monasteries because I know he wouldn’t care if he missed that sort of thing.

I walk up the hill from the phone booth and see an advertisement for a company that drives its customers to Khardung La—the highest motorable road in the world—and then lets them ride mountain bikes down, back into town. It sounds awesome, and doesn’t require long stays at high altitudes. But I’m sure that this is something I should do with David. For a moment I forbid myself to have any fun. That moment lasts a few days. I restrict myself to the monasteries because I know he wouldn’t care if he missed that sort of thing.

I’ll come back and do the bikes some other time, though I know I’m not coming back at all.

___

I make traveler friends. The British girls, another man from the U.K. in town to teach, an Israeli, a couple Indians in Ladakh for trekking, a German guy, and a French man, as well, I think. We eat dinner together and sometimes lunch, too. At first I hate the conversations: where have you been, where are you going, what have you seen, what you should see, how much you’re paying  for your guest house, how there are a million cheaper places, how there is always something better, more amazing, more peaceful, further away from the rest of the world. Everyone has their best, favorite places. Everyone has their knowledge of the world and its secrets.

for your guest house, how there are a million cheaper places, how there is always something better, more amazing, more peaceful, further away from the rest of the world. Everyone has their best, favorite places. Everyone has their knowledge of the world and its secrets.

But eventually, these friendships accelerate and pass the usual backpacker one-upmanship and note-comparing. Eventually the conversations turn towards families, towards the way they approve or do not of our collective wanderlusts, towards illicit international romances, towards how we feel as we celebrate a birthday so far from home and the people we love or think we love, how we latch on to one another so quickly in grungy little restaurants that serve killer Tibetan momos. We find out about another’s careers—their starting or failing or refusal to present themselves altogether. Inevitably, we are all flight risks, we have all come running from something and towards something else. This is what forces us together in these high mountain towns. This is what makes me stop feeling lonely.

___

From the big balcony attached to my room, I look out on the Zanskar Range. I’m saying thank yous to the world, to the skinny poplar trees and the valleys and ravines and impromptu mountain blizzards. In these eight days the moon has grown steadily brighter, on its way to an engorged show for Buddha Jayanti, which I will be celebrating in Bodhgaya, where the Buddha attained enlightenment. But as the moonlight grows louder, the million and one stars in the sky seem to die. They disappear and fade until on this last night it is just a blaring round hole in the inky sky. The light makes the snowcaps glow, makes the shadows heavier and the rest of world a dark quiver.

Now that it is time to leave Ladakh, I would like to stay. The enormity of this chance hits me all at once—that this is something once in a lifetime; that I’ve spent eight days wound up in baseless worries and simple human longings. I wish I could have put myself to the side. I would like another shot at all of this, way up here, in this part of the world so very cut off from the rest.

My skin prickles in the cold breeze. I wonder which glaciers the wind has passed, exactly which version of cold is caressing my arms. This is something I would like to know. Did it come from Tibet? From that holiest peak, Mount Kailash.

Tell me that’s where it came from; that the wind I’m feeling means something more than wind.