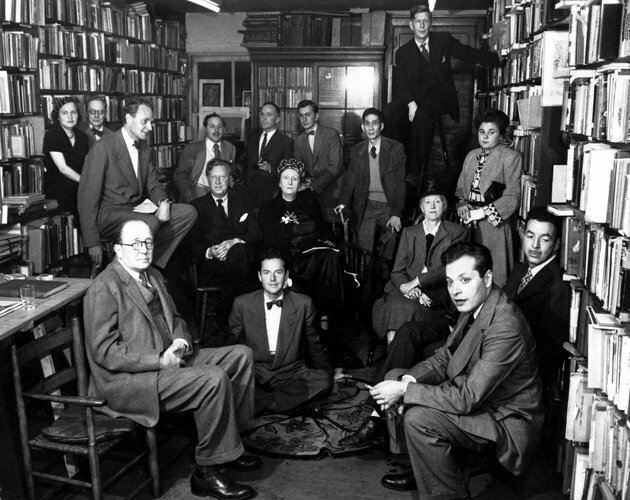

Characters:

Wallace Stevens

Marianne Moore

Elizabeth Bishop

W.H. Auden

James Merril

Robert Lowell

Introduction

Lowell: Why are we here? Can someone tell me this, please?

Auden: A little testy, aren’t we?

Lowell: Testy? Of course. I was not planning on being summoned from the grave today, and in fact had plans this afternoon with my dead first wife.

Bishop: Do you mean Jean?

Lowell: Yes, I mean Jean. We were going to visit Boston, MA, so that I might once again visit the stomping grounds on which I bullied my classmates and earned the nickname “Cal.”

Bishop: Short for “Caligula.” And you’re proud of this?

Auden: Proud? He’s positively beaming, the old bully.

Stevens: Bully indeed. I agree with Mr. Lowell, this is a most wretched occasion for being summoned. The malady of the quotidian? I meant to say the malady of the long dead.

Merrill: An elegant turn of phrase, Mr. Stevens – just superb. But less we stray too far from the reason why we have been called from the dead, I suppose I must ask aloud, Who called, and what are we doing here? Where are we, anyways?

Moore: I called. This is my summoning.

Lowell: A-ha! So this is your doing, eh Ms. Moore? Getting lonely with only your mother in the afterlife to tend to your exacting observational powers?

Auden: “To tend to your exacting observational powers”? What happened to the antithesis of long-windedness you developed in Life Studies, by dear Robbie?

Moore: Enough. I called us together for a conversation.

Merrill: A good enough reason.

Auden: Agreed.

Bishop: Hear hear.

Lowell: Yes, and all that.

Stevens: Indeed. But pray tell, Ms. Moore: a conversation regarding what?

Moore: Regarding John Ashbery, my dear poets.

Lowell: Oh god, here we go.

Bishop: Cynical, Robert?

Lowell: Cynical? More like “risible.” I have a deep distaste for that silly man’s work.

Merrill: Ha! “Silly man”? Do explain yourself, dear Caligula.

Lowell: But where to begin? I coined, many years ago – that is, I stole, many years ago – the phrase “raw and the cooked” to describe the difference between my early work and the work of, say, Ginsberg. And yes, with Life Studies I did leave the cooked for the raw. But my poetry always maintained some aspects of the cooked – a certain formality, even in my autobiographical writings. Ashbery, on the other hand, is the rawest poet I have ever encountered, by which I do not mean to praise, but rather simply observe with some disdain.

Bishop: But do explain yourself, Robert. What you mean by “raw,” I mean.

Lowell: We might as well recite something. Here, look at this poem from the poet’s first well-received book, Some Trees. I do not wish to look at the more canonical works – “Instructional Manual,” “Some Trees,” “Illustration,” or “The Painter.” Let us look at something more “minor.” Ah! Here: “Sonnet.” Good and short. (Clearing throat)

Each servant stamps the reader with a look.

After many years he has been brought nothing.

The servant’s frown is the reader’s patience.

The servant goes to bed.

The patience rambles on

Musing on the library’s lofty holes.

His pain is the servant’s alive.

It pushes to the top stain of the wall

Its tree-top’s head of excitement:

Baskets, birds, beetles, spools.

The light walls collapse next day.

Traffic is the reader’s pictured face.

Dear, be the tree your sleep awaits;

Worms be your words, you not safe from ours.

Fellow poets, how are we supposed to read something so surreal, so nonsensical? I’m baffled.

Moore: Great question, Mr. Lowell! How do we read this poem?

(Long pause in the conversation as the poets begin thinking.)

Musicality and Narrative

Auden: I feel I owe some explanation for the poem, as I did choose John over his friend Frank O’Hara for the Yale Younger Poets Prize. Back then, I explained that John’s poetry was interesting but dangerous; that it was an interesting experiment, but that too much nonsense could deprive his poetry of too much meaning. And that would be bad.

But let me try to say more, now, about what I liked about John’s poetry, and therefore what I also admire about “Sonnet.” To begin with, a reader must always interrogate his or her own assumptions about what it is he or she likes about poetry. By self-interrogation, I do mean something analogous to the intention of psychoanalysis – that is, the better a reader understands his or her own predilections, the easier it will be for said reader to find the literature that moves this reader the most. Now, the reason I like “Sonnet” – and I know we cannot stay merely on reasons for “liking” the poetry, but I find it a fine place to begin – the reason I like “Sonnet” is because, like my own early work, Ashbery is developing a different way of talking.

Bishop: How do you mean, “a different way of talking”?

Auden: Well, if you can suffer through it, let me recite from memory one of my earliest works, entitled “Taller Today.” Afterwards I”ll explain why. (Clears his throat.)

Taller today, we remember similar evenings,

Walking together in a windless orchard

Where the brook runs over the gravel, far from the glacier.

Nights come bringing the snow, and the dead howl

Under headlands in their windy dwelling

Because the Adversary put too easy questions

On lonely roads.

But happy now, though no nearer each other,

We see farms lighted all along the valley;

Down at the mill-shed hammering stops

And men go home.

Noises at dawn will bring

Freedom for some, but not this peace

No bird can contradict: passing but here, sufficient now

For something fulfilled this hour, loved or endured.

Merrill: Beautiful. But do explain.

Auden: I believe this poem works for two reasons – one because of its music, and secondly, because of its approximation to narrative.

Lowell: And by “music” you mean…?

Auden: This is hard to say. Yet I think I mean something akin to the music that Mr. Stevens creates in his poetry. Do tell us, Mr. Stevens, how you understand what I mean when I refer to the haunting musicality of poetry, and then I shall be happy to continue.

Stevens: I’m not very comfortable discussing my own work, Mr. Auden.

Auden: Humility, expressed grandly! I appreciate the sentiment, Mr. Stevens. Well, let us return to you in a second. What I mean by musicality is something I believe Mr. Stevens refers to in his “13 Ways of Looking at a Blackbird:” I mean “the beauty of inflections” and “the beauty of innuendoes.” For poetry doesn’t necessarily sound like human speech. I know this sounds shamelessly obvious, but occasionally what is obvious needs to be emphasized, in case it is forgotten, shamelessly. Poetry is not simply embellished speech given a meter. It is a deeply strange and other way of speaking, with roots I would imagine in divination. It is magical. And yet what makes a phrase magical? It’s sound. Therefore, notice the sound of “windless orchard,” “lonely roads,” “Nights come bringing the snow, and the dead howl”. These are haunted, haunting phrases, and they are haunting and haunted because they are other. No one would say, in a conversation, “nights come bringing the snow,” just as no one, doodling in their notebook, would draw an enormous abstract painting the size of ten men. Such experimentation in language, like experimentation in form and color in the visual arts, heightens and augments our consciousness of language, the way that painting does the same for form, shape, color, and line. It is a seemingly deeper way of talking. And this depth, this haunting quality, is what I mean by “musicality.”

Merrill: Interesting, Wystan.

Auden: Thank you. But now, Ashbery’s work. I believe it carries this same sort of musicality. But moreover, it is a musicality that is Ashbery’s alone – he sounds like himself, and no one else.

Bishop: But what about “Some Trees”? I’ve always thought he sounded in that poem like you, Wystan.

Auden: Well, I mean as he develops as a poet. But notice some of the turns of phrases in “Sonnet,” (named, I noticed, Elizabeth, similar to your great poem, “Sestina”). “After many years he has been brought nothing.” “The light walls collapse next day.” These are assertions which are completely nonsensical. They combine the confidence of assertion with the artifice of imaginative freedom. It is for that reason they are so strange, yet lovely and, in a way, hauntingly enigmatic.

Moore: So, Mr. Auden, are you saying you like John’s poetry because he writes creative phrases?

Auden: No, but I think that is a part of it. What I’m saying is that what John is doing is harder than it looks. Here: everyone come up with a nonsensical phrase. I’ll give us ten seconds. 10….9….8…..7…..

Moore: The pelican’s head was a grouchy artichoke.

Bishop: The sandpiper’s library is a crumb of an almanac.

Stevens: Far from the languorous sea, a dog’s asbestos legs rang vividly.

Merrill: Dear, please send me those pool balls shocking the nerves of a kimono.

Lowell: Damn garret in the house sets my cigarettes to flame!

Auden: “Traffic is the reader’s pictured face.”

Lowell: But that’s a line from the poem.

Auden: Yes. I wanted to juxtapose our “nonsensical” statements, in order to show that John’s line is not very nonsensical. In fact, of all the phrases we came up with, I would say that the line “Traffic is the reader’s pictured face” is a very interesting kind of metaphor, which – in a shockingly disturbing way – seems to serve as a mirror for the reader’s own experience reading the Ashbery poem. For aren’t we all, facing “Sonnet,” as confused as a pattern of honking gridlock?

Bishop: So “Sonnet” is a mirror for the reader’s face? And what happened to the “story” you mentioned, along with the musicality?

Auden: I’m getting there. But notice the phrases in “Sonnet.” “Each servant stamps the reader with a look./ After many years he has been brought nothing. / The servant’s frown is the reader’s patience. / The servant goes to bed. / The patience rambles on / Musing on the library’s lofty holes.” Notice how each line is a separate sentence, until the final enjambed line, which is sensible, for musing is a longer process that would carry itself over, past a shorter sentence. Now, is it dangerous to say that it is as if Ashbery were voicing some of our own experiences reading the poem? For what if we were to replace “servant” with “writer”?

Each writer stamps the reader with a look.

After many years [the reader] has been brought nothing.

The writer’s frown is the reader’s patience.

The writer goes to bed.

The patience rambles on

Musing on the library’s lofty holes.

It makes more sense now, doesn’t it? Ashbery, equating the writer with a servant – perhaps who who serves creativity, imagination, new ways of thinking and talking, poetic knowledge and experience – describes one experience reading a poem. The writer makes the reader pause; the reader feels frustrated; the writer, echoing the reader’s frustration, makes the reader feel less frustrated and more patient; the writer leaves the reader, or the reader puts down the book; the feeling engendered by the skillful writer hangs in the air of the reader’s mind like a powerful lingering scent; and this lingering somehow muses on “lofty holes” in the library – perhaps a metaphor for the strangeness of the familiar.

Stevens: Bravo, Wystan! A very nice interpretation.

Auden: But I’m not finished. First, we can sense the uncanniness of the passage now, a little closer. And yet we can also see how John’s work gestures towards narrative, without becoming a narrative itself. It is suggestive – something Marjorie Perloff has also written about. And here it is suggestive, because it seems, in some very bizarre and weird way, to be ahead of the reader, to out-anticipate us, and know our expectations before we ourselves know them.

Moore: So Ashbery knows us better than we know ourselves. A discomfiting position, to say the least. But what does it actually mean?

Installation Art and Complex Moods

Merrill: I think it means something like this. Take Proust for example, that remarkable exemplar of the winding sentence brooking no obstruction, who wove tapestries of sentences that, in their unwinding joi de vivre, wove us different faces, different ways of thinking about and imagining ourselves. Proust set out to write a book, and the book turned out to be a book with a style innovative enough to spawn myriads of imitators. Why would people try to imitate the master? I believe because it was as though Proust had placed a new face us for within our own hall of mirrors. He had imagined himself and others within a new kind of vocabulary, a vocabulary that stretched our self-image, made it more elastic, more expansive, less fixed or dull. Is this what you believe Ashbery is doing, Wystan?

Auden: Precisely.

Moore: But then what is the difference between sense and nonsense? Wallace, you are famous for saying a poem, pardon the paraphrase, “resists the intelligence half-successfully.” Do not Ashbery’s poems err too much on the side of the resistance?

Stevens: I have wondered about that, especially in the poet’s second book, “The Tennis Court Oath.” For what do we do with passages like, (and this is from “How Much Longer Will I Be Able to Inhabit the Divine Sepulcher…”, a more-praised poem from the book):

Stars

Painted the garage roof crimson and black

He is not a man

Who can read these signs… his bones were stays…

And even refused to live

In a world and refunded the hiss

Of all that exists terribly near us

Lilke you, my love, and light.

I mean, this at least makes some sense, and comes from a poem that itself makes some sense. It is as if Ashbery were giving us some raw blocks of experience, some raw linguistic (and poetic) data, and were asking us to assemble this data in a way in which it makes sense to us. Like a piece of installation art. We walk into this installation, grabbing at particulars that appeal to us, and with these particulars we form our own experience of the artwork. Perhaps Ashbery is simply calling overt attention to the way in which we actively construct meaning.

Bishop: Yes, but then what of the very obscure Ashbery, such as his “Europe”?

Moore: Elizabeth, give us an excerpt.

Bishop: Alright. Here is the opening four sections of “Europe.”

1.

To employ her

construction ball

Morning fed on the

light blue wood

of the mouth

cannot understand

feels deeply)

2.

a wave of nausea –

numerals

3.

a few berries

4.

the unseen claw

Babe asked today

The background of poles roped over

into star jolted them

Now I find these passages suggestively rich, but too lean on the meaning to satisfy.

Lowell: I agree.

Moore: But isn’t that exactly the point? Isn’t the poet simply experimenting, like any poet, with how much he can give us, and how much he can hold apart?

Merrill: John Shoptaw’s book, On the Outside Looking Out, illuminates what “Europe” is ostensibly about. But imagine if we had not read this book; what would we make of this poem?

Stevens: I confess I have never been able to finish it.

Bishop: Ditto.

Auden: Harold Bloom claimed it was an abomination, to put it mildly.

Stevens: Yet other poets, like Charles Bernstein, have claimed it as an important poem, one that figures as a precursor to the Language poets’ experiments.

Moore: So what is it? An abomination? A prescient experiment? What?

Bishop: I think this depends on the reader’s taste, to be honest. If the reader enjoys a poet who does not make overt meaning, but gives us the building block of sense, of intelligence, of imagination, of memory, and asks us to do with it as we please, then perhaps The Tennis Court Oath would be their favorite book. For my taste, I enjoy the Ashbery who does more with meaning then simply barely alludes to it. I like the Ashbery that is funny, that writes long sentences with their own idiosyncratic elasticity, that is brimming over with original ideas, that is wacky, that is fun.

Moore: Is there a specific poem you are thinking of?

Bishop: Yes, actually, Marianne. I’m thinking of “The Skaters.”

Moore: Let’s hear some of it, keeping in mind that it is a much longer poem.

Bishop: Indeed, let’s do that. “The Skaters” begins with these two stanzas:

These decibels

Are a kind of flagellation, an entity of sound

Into which being enters, and is apart.

Their colors on a warm February day

Make for masses of inertia, and hips

Proud out of the violet-seeming into a new kind

Of demand that stumps the absolute because not new

In the sense of the next one in an infinite series

But, as it were, pre-existing or pre-seeming in

Such a way as to contrast funnily with the unexpetedness

And somehow push us all into perdition.

Here a scarf flies, there an excited call is heard.

Bishop: Many critics have pointed out that Ashbery is hearing the sound of people ice-skating, that these sounds are the “decibels” that are “a kind of flagellation, an entity of sound / Into which being enters, and is apart.”

Imagine the poet typing beside a window, and he hears the sound of the ice-skaters. The sound allows him to in some ways “enter” the scene, participate in it, but at the same time the poet is distant, apart from the scene, both in the game and out of it. The sound of this activity does not make the poet want to ice-skate, but rather makes “for masses of inertia” that paradoxically make a demand on the poet. What is the demand that “stumps the absolute”? It seems as though Ashbery is commenting on a preternatural quality of the ice-skating – that the sounds and colors seems somehow to have already existed, that they are a kind of given, a kind of fore-grounded immanence, as opposed to a receding transcendent that constantly eludes the poet; but that this preternaturalness, this givenness of the skaters, contrasts funnily with the way in which their sounds are “unexpected.”

One might therefore create an analogy between the experience of the sounds and colors of the skaters, and the experience of the tradition of poetry within which Ashbery writes. Both the skaters and the tradition are simultaneously given and surprising, old and new, expected and unexpected, traditional and innovative. Ashbery himself, steeped in French poetry, in the works of poets as varied as Pasternak, Rimbaud, Stevens, Auden, the Metaphysical poets, Whitman, etc., still finds a way to make it new. Thus Ashbery is commenting on a dynamic that is rife throughout his own work – the play between the old and the new, between originality and continuity. Indeed, as we read further, Ashbery writes,

The answer is that it is novelty

That guides these swift blades o’er the ice,

Projects into a finer expression (but at the expense

Of energy) the profile I cannot remember.

Colors slip away from and chide us. The human mind

Cannot retain anything perhaps but the dismal two-note theme

Of some sodden “dump” or lament.

But the water surface ripples, the whole light changes.

As you can see, Ashbery now is sort of expanding on this dynamic between innovation or “novelty” and older ways of being. It’s as if we are watching a symphony of colors, light and dark, and the light stands for novelty, which can be exhausting, and the dark stands for habitual ways of living, which can also be exhausting. So that Ashbery is navigating himself and us through this symphony of colors, through desire for change and desire for certainty. We hear that these “Colors slip away from and chide us”, perhaps suggesting that they bring to the poet a kind of regretful nostalgia. And indeed, “The human mind / Cannot retain anything perhaps but the dismal two-note theme / Of some sodden “dump” or lament,” meaning that the human mind is incapable of nothing except a kind of familiar, weary lament, an existential complaint. “But the water surface ripples, the whole light changes” – and yet, and yet, and yet. As you can see with the two stanzas that are sentences –

Here a scarf flies, there an excited call is heard.

and

But the water surface ripples, the whole light changes.

The changes in the activity of the skaters, which seem to precipitate changes in the poet’s mood and mind, consequently precipitate changes in the mood of the poem, and pragmatically effect transitions in the poem from one mood or sentiment to another. We are all going to hell, the first stanza suggests, but “Here a scarf flies, there an excited call is heart.” All we can do is listen to the sad horn in our mind, “But the water surface ripples, the whole light changes.” It is akin to a sad mood interacting with a gloriously aesthetically pleasing landscape – in that bittersweet confluence of longing and temporary satisfaction, we have a tonally rich experience that demands a poem (as Ashbery recognizes, and delivers) to do justice to the pungent, fragrant, potent contours of that experience.

Moore: Bravo, Elizabeth! But you said earlier that Ashbery is a funny poet…?

{ 0 comments… add one now }