Prayer for Topaz, 1942

Dear God,

Mom said you are busy and don’t have time to listen to a little 8-year-old Negro girl from North Carolina and her foolishness, like praying for a box of candy. That would be selfish. But if it’s really important she said, then I should take it to you in prayer like the preacher says on Sundays.

I’m not asking for anything for me. But I’ve been hearing the kids at school talking about some place out west called Topaz. At first I thought they were talking about a spot to get rings and flashy jewelry, but Margaret’s big brother, Ed, who’s in 5th grade, says it’s something like a jail where they put Japanese people. I didn’t believe him because he’s always trying to scare us girls. So I asked my dad, and he said it’s true. The government put them there so that the country would be safe. I know that some Japanese airplane men did some bad things in Hawaii back before Christmas, but the people they put away aren’t from over there. They’re Americans and some have been here since before I was born. Some of them are just tiny little girls like me.

I know, God, I’m young, but I really don’t understand how the government thinks that a little Japanese girl could hurt this big country. Anyway God, I’m praying for you to take care of those little Japanese girls and boys. I hope they have some toys to play with and maybe some candy. I hope they get to go home soon.

And God, while you are doing that, could you also watch over me and my family and all of us at school. I worry that we might be next.

_________________________________________

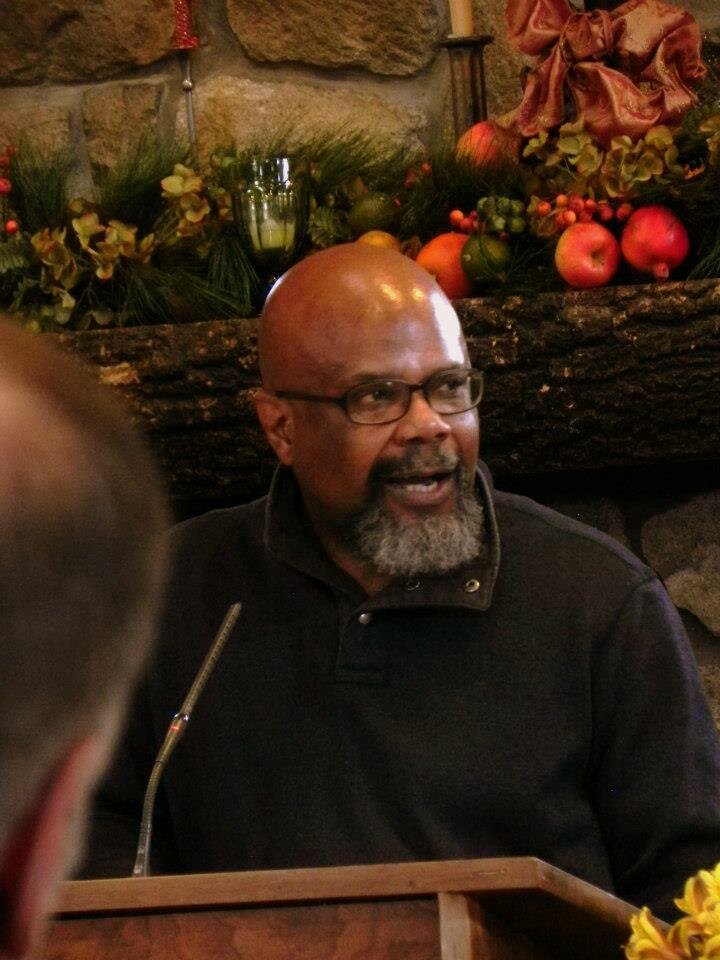

Le Hinton is the author of five poetry collections including, most recently, The Language of Moisture and Light (Iris G. Press, 2014). His work can (or will) be found in journals such as Little Patuxent Review and the Baltimore Review, anthologies such as The Best American Poetry 2014 and outside Clipper Magazine Stadium, incorporated into Derek Parker’s sculpture Common Thread in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.