Saumya Arya Haas is an ALB candidate in Religious Studies at Harvard University. She lives with challenges due to a Traumatic Brain Injury. Prior to this life-altering injury, she engaged in interfaith/intergroup dialogue and Social Justice projects, advising organizations such as and , and has worked with the Parliament of World Religions, The UN World Council of Religious Leaders, and The UN Peace Initiative. Her work has taken her everywhere from West Africa to the White House. She is a regular contributor at , , and . Her writing can also be found on various other websites and in print media. Saumya is a priestess of both Hinduism and Vodou.

Fox: Thanks so much for coming to talk with us about your love of art and your writing life. I know you’ve published a lot of writing — on religion, on culture, and journalistic pieces — but you mentioned to me that you haven’t published a lot of poetry yet. I’m interested in how you got into writing. What pulled you into the kind of writing you do for HuffPo? What got you into writing in the poetry genre from there?

Saumya: I’ve always been a writer. I come from a family of writers (both my parents are writers and poets; my mother is also a visual artist) so I was encouraged at a young age…not just actively encouraged by my parents, but by being immersed in a family culture of reading, intellectual discourse, and self expression. I have dozens of journals of writing from my life and travels. In the late 1990s a I took a series of Creative Non-Fiction writing classes at Minneapolis Community College, and my professor encouraged me to submit one of my essays for publication; it was featured in a print anthology, but for many years after that, my writing was on my personal blog or for my interfaith and global education work.

My interfaith work was in cooperation with diverse organizations at the start of the social media explosion, so I was also responsible for blogging about our projects. One of my colleagues, a leader in the Hindu-American community, wrote for various religion and news websites. She liked my writing and invited me to submit something to her editor at The Washington Post. I was thrilled. This led to my work with Huffington Post, State of Formation, and other media sites. It’s hard to explain how it feels, as a Hindu American woman, to share my perspective with a national audience.

It’s easy to forget that, until quite recently, media was dominated almost exclusively by white male perspectives and the definition of “mainstream” was very narrow. There was little space for women, writers of color, and religious minorities to share their views with a wide audience. Although it’s still unbalanced today, it is possible (with an internet connection) to share and find more diverse representations of reality.

I have always written poetry but it’s not something I feel competent with. Many of my poems started as a few lines jotted down on a scrap of paper, intended to become a prose piece. Sometimes I get words or lines bouncing around my head and I just want to get them out. I love to read poetry, but it never occurred to me that I was a poet.

Fox: One of the things I love about this poem appearing on Poetry Blog today is that it addresses so many things — experiences of culture and gender and religion — in a contemporary, edgy way that feels very fresh to me. Can you tell us a little bit about your religious background? How does it inform this poem, and your other writings? How does it affect the way you think about gender (if at all), or the way you experience American culture (if at all)?

Saumya: I am Hindu by birth and inclination. “Hindu” means so many things! There are many Hinduisms and I only speak for my own experiences.

My Hindu heritage is from two different continents, and inextricably linked with social justice work. My father is a Hindu priest and was born in India during the British Raj (i.e. Colonialism). He was raised in a very traditional way; his first language is Sanskrit. His work with Hindu communities took him from India to Kenya to Guyana, where he met my mother. My mother’s family is also Hindu, and originally from India, but some generations back were taken by the British to the Caribbean (in our case, Guyana, Surinam, and Trinidad) as Indentured Workers. While the Indian Diaspora community did not suffer the egregious wrongs of generations-long slavery, our cultural experience is not unlike that of the African Diaspora. One (of many) differences is that only a few generations elapsed for the Indian community, so there was contact with India My mom’s family were part of a Hindu group called the Arya Samaj, which among other things, was concerned with gender equality. My grandmother and mother were publicly acting as Hindu priestesses in Guyana at a time when, in India, this was probably rare. My mother grew up during a very tumultuous and violent time in Guyana’s history, so being a priestess was not just religious work. My family, especially the women, were community leaders. My parents were brown people from Colonial countries during the occupations and fall of the British Empire. Any cultural or religious expression was inextricable from social and political activism. Soon after Guyanese independence, my parents moved to the United States for my father to teach Sanskrit at the University of Minnesota. I was born here.

The Hinduism my family practices is an intellectual, philosophical tradition that is both, either, or neither theist and non-theist. We consider the existence or non-existence of God (and what one means by “God”) as a question with infinitely variable answers that it’s fun to discuss but not worth worrying over. We generally leave God out of it and move on the interesting issues of how humans experience reality, and how to make that experience productive for each person.

These are the very basics of our Hindu philosophy: to explore a statement, one has to consider that

It can be true

It can be not true

It can be both true and untrue

It can be neither true nor untrue.

This is not mainstream Hinduism, but our tradition is ancient. It also includes things like Yoga and meditation: ways of improving one’s life, with or without being attached to a particular religious or cultural tradition. We also perform regular Hindu rituals, so as priests and priestesses, we serve multiple purposes and communities.

My parents founded one of the first Yoga and meditation studios in the Twin Cities, and I went to Catholic School. I learned to describe, and defend, my Hindu religious culture at a young age. Besides that, I was a normal American tomboy. I was horse crazy. I rode my bike around the neighborhood and played baseball with my friends. I liked loud music and was not afraid to get into physical fights. On Fridays, I went to church at my school. On Sundays we had a traditional Hindu havan (fire ceremony) at home. To most of the people I met outside our home, Christianity was the norm. We didn’t fit.

When I was ten years old, we moved to India. I insisted to everyone that I was not moving “back” to India. I had never been there. It was not my country.

In the mid 1980s, India was very cut off from other countries: there was no internet then, and all the things I liked were unavailable. Last summer I went to see “Guardians of the Galaxy.” You know how Peter Quill was with his walkman? That was me: plugged into American music while negotiating an alien landscape.

We lived in a small city. The social expectations for girls (be quiet, get married) were ridiculous to me. Because my father was a well-known priest and a public figure, those expectations were doubled for me and my sisters. I, to put it lightly, rebelled. I avoided wearing Indian clothes and stuck to jeans and Tshirts at a time such clothes were considered slutty and revealing. I had this weird baseball-type hat with bright orange wings sticking out from it that I wore everywhere. People thought I was crazy. I don’t mean crazy in a quirky, endearing way. I mean: crazy.

Being a girl meant being demeaned and sexually assaulted pretty much every time I left the house. Unlike the vast majority of Indian girls, I did not tolerate or ignore this. If a guy, often a grown man, grabbed or groped me, I turned around and punched him. If he didn’t desist, I beat the crap out of him. To everyone around me, these men’s behavior was the norm; ignoring it was the norm. No one could understand why I was so angry.

Girls did not go out alone, for obvious reasons. I discovered a local riding stable, and began to go out by myself on horseback. No one had ever seen a girl on a horse. I was painfully visible. Men would block me from passing on narrow roads; I perfected an echoing war cry that startled them out of the way. I was pulled from my horse by my dupatta (a long scarf that is a staple of north Indian women’s clothing) and sexually assaulted; I stripped myself of all loose clothes and adornment and that could be grabbed, and carried a thin, whippy branch to defend myself. I was run off the road by a group of guys on motorcycles; I figured out that a horse is a thousand pound weapon. I was in a legitimately cinematic horse vs. car chase over miles of deserted mountain roads and trails; I acquired a dagger. Between the ages of eleven and fourteen, I punched, whipped, kicked, slashed, knocked over, ran down, and thoroughly cussed out more men than I can count. I learned when to just keep riding.

People ask me: where were your parents while this was going on? My parents did not like me riding by myself so I didn’t tell them anything. If I came home bruised, I said I fell off my horse. Sometimes this was true.

I didn’t want to be Indian, or Hindu, or a girl. I was at an age where my sexuality was awakening and I wanted to express myself in some new way. All the social messages around me seemed to conflate womanhood and victimhood. I was surrounded by images of powerful Hindu Goddesses, but being a woman was to be powerless. I had had profound experiences in temples, but I could see no separation between the expression of religion and the abuse I experienced every day. I didn’t know how to parse out the strands of becoming a woman. I didn’t know how to parse out the strands to make peace with my reality or myself. I fought everything.

Traditional adornment was certainly not my thing, so when my mom insisted that I get churis (glass bangles) for someone’s wedding, I resisted. I did love the bangle shop; it was kind of like Olivander’s Wand Shop from the Harry Potter movies: dusty boxes piled everywhere, opened to reveal sparkling magic (it has not escaped me that I often turn to sci-fi and fantasy to explain the plain realities of my experience).

The guy slid bangles on my wrists, and, knowing me well, told me how I could use them for self-defense. I was stunned and delighted. (BTW I do not endorse this, because it is insane and you could injure yourself, but if you find yourself in trouble with nothing but glass bangles to protect you, use the outside of your arm. The skin is thicker, and you don’t have major veins to worry about.) I will always remember that he said “adornment does not only serve one purpose.” My first inkling: I could enjoy traditional symbols of womanhood, AND I could continue to defend myself. Even better: feminine trappings can be a defense. Take that any way you like.

Soon after acquiring those first bangles, I tried to kill myself.

At the age of fourteen, with my parents’ full support, I left India to attend a boarding school in the UK. It was a wonderful, transformative experience. I eventually made my way back to Minneapolis. For many years, I did not want to have anything to do with India or Hinduism. I wanted to wipe out those traumatic years and just be American. I shielded myself in the trappings of America in defense against all the things I didn’t want to be. At the same time, I was interesting to my American friends because I was different. My past became fabulous stories; telling my stories became a sort-of performance art. I viewed my stories in a way that was distancing. I simultaneously expressed and separated parts of myself. I lived through an uneasy, ambivalent process of exotifying my past and my self.

Reality seeps in. Gradually, in fits and starts, I accepted that my experiences and my heritage were powerful, close, and necessary. Wearing bangles or being Hindu or being a woman means whatever I make it mean. It’s not my business what those symbols or words mean to other people. However, not caring about something does not insulate us from being affected by it. Wearing Indian jewelry or clothes in Midwestern America makes me visible in a way that can be uncomfortable; especially since 9/11, people can be hostile. Never mind the jewelry; I’d just like to be able to wear my skin color without people assuming that they know something about me because of it. I love this country, but it can be hard to live in. We have to carve out a space that suits our shape. I feel the same way about my religion, my adoptive countries, my everything.

We are living at a time that women’s and minority voices are (starting? sometimes?) to be heard; my parents fought for that, many people still fight for that. It’s a privilege I don’t intend to squander. So while I say “it’s not my business what people think” I contradict myself and make it my business by writing things that challenge limited perspectives. As a Hindu-American, I write to inform non-Hindu (usually Christian) Americans about my experiences. As a Hindu woman, I am often addressing Hindus in America, in India, around the world. I am part of these communities, but I am also apart from them. When I was a girl, there was nothing around me, nothing, that acknowledged my experiences and struggles; I don’t want other girls and women to be as isolated as I was.

Now, when I tell or write my stories, it brings them closer, not further away. In writing, I learn to own myself, even if there are things I would like to forget. Making myself visible through my writing is often uncomfortable. Being visible still feels dangerous. I try to live more honestly with both my trauma and my power. I’ve learned to live in, and with, multiple realities: Hindu, American, Indian, woman. Each of these encompass so much, and my experience is different from the thousands of people who identify with those labels. The only place all my diverse realities intersect is me; this is true of everyone. We are the result of, and subject to, so many intersections. Writing is my way of also becoming their custodian.

This is why I write. It’s not just to educate or inform others; it may to an attempt to change the norm, but it’s also an attempt to understand it, and to understand why and how I don’t fit. I don’t think my ambivalence will ever go away. But I keep writing. I am a soft-spoken woman who has dedicated herself to interfaith and intercultural understanding, but I’m also the girl who once rode a horse through a riot.

Fox: I’ve been talking with some of the other TheThe Editors lately about my idea of a “visionary poetics” — a kind of aesthetic in poetry that is informed by mystical experience, occult knowledge, or religious life — that is interested in metaphysical vision, but also in looking at things on multiple levels or planes of existence — looking at this world, too, and the connections and conflicts and contradictions in it, and trying to say something about how to envision it all together. Based on these ideas that have preoccupied me lately, I’m curious whether you think that your background as a Hindu priestess and a Vodou priestess shape your approach to writing and/or art — as someone who creates art and literature, but also as someone who loves and appreciates art and literature? If so, I’d be interested in hearing about how.

Saumya: I don’t think I can separate myself (my “self”) from my religions. For me, the task of creation is sacred, as is the result. Creation of art is a mystical experience, as is the experience of encountering art that resonates with us personally. There is something about art that, for me, goes beyond even my pagan-rooted appreciation and connection with nature, because with art, we know that another human being created it. The beauty and courage (creation is an act of courage) that humans hold within themselves, and share so freely, is astonishing to me.

Poetry is sneaky. It is faster than our reflexive deflections. So it is the perfect medium to communicate mystical, emotional experience. We can reason and argue and cite our sources, but none of that can make someone change their mind; reason is useful, but it’s hard. We can’t often reason ourselves (or someone else) into feeling or not feeling something. Poetry is like music. It comes through our skin, not our minds. It makes us not just feel, but experience something. It’s a tuning fork that reverberates through our walls and makes us shiver. It lets others in.

I am eternally the “other.” I have never lived somewhere where I was not a minority. Even in India, which is 80% Hindu, the type of Hinduism my family practices is obscure. Unlike being a minority due to my skin color, I have (and have had) a choice to remain a religious and philosophical minority. I have never been able to comfortably absorb the surrounding cultural assumptions. While this can be difficult to live with, it’s also very freeing. I question everything (I’ve been told this is also very annoying). When I listen to people who are critical of their culture, I’m delighted, but I often feel that it usually only goes so far. Most people, especially in the – what to call it? Northern Hemisphere, the West? get stuck in duality: either something is true, or it is false. I am lucky enough to have encountered, studied, and experienced more expansive philosophies. How can I communicate those realities to someone else? When reason and argument fail, I turn to poetry and art.

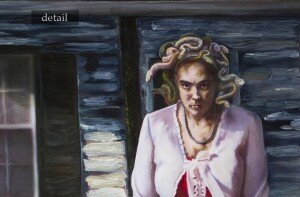

In this, I am part of a long tradition. I can explain all about the Hindu Gods or Vodoun Spirits; I can share their resumes, as it were, talk about what they symbolize and the history of the cultures that worship them and bla bla bla but all of that intellectual stuff falls short. You want to know about Hinduism? Turn off the lights, kindle an oil lamp and watch the light flicker on Shiva’s face. Let me take you to the Himalayas. Stand within a temple carved by human hands expressing the divine. You want to know about Vodou? Come to a ceremony. Dance. Put your feel on the soil of Benin. There are many ways (certain geographies help, but they are not necessary). The words fall away and you don’t understand, you encounter. It is so much more.

How does this influence my writing and art? I have no idea.

Fox: What’s the most challenging piece you’ve ever had to write? What was especially difficult about it? Were you able to finish it to a point where you were satisfied with your results? If so, how did you get there?

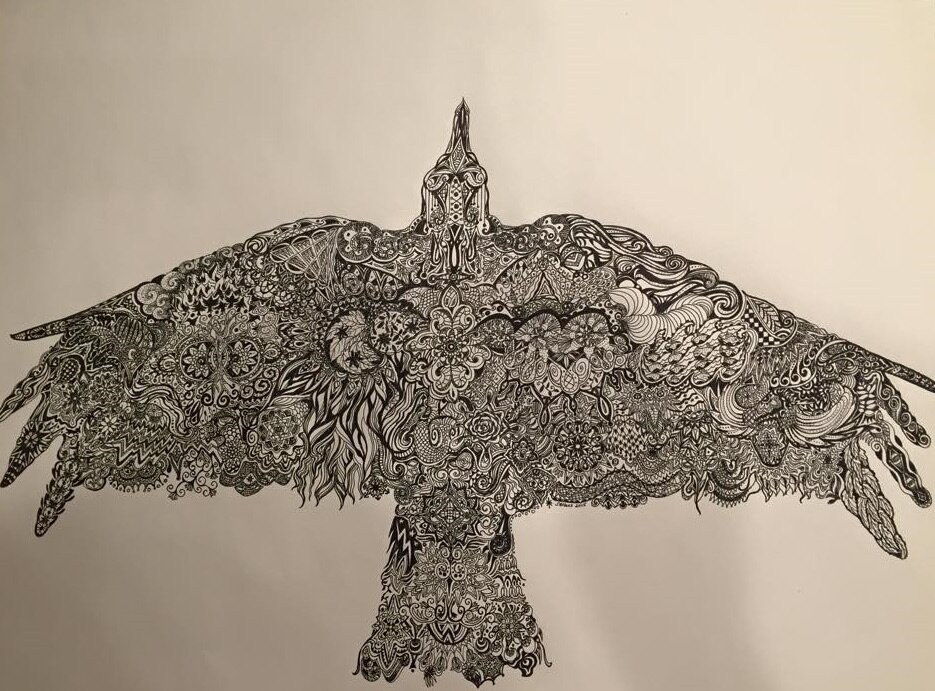

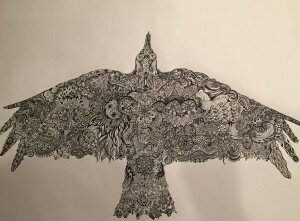

Saumya: When I was thirteen, I witnessed a murder during a religious riot, after the (Hindu) Prime Minister of India was assassinated by her (Sikh) guards. In the aftermath, an unknown number of Sikhs: men, women, and children, were killed by Hindus in “retaliation;” there are some very strong allegations that people within the (predominantly Hindu) Indian government were complicit in, or encouraged, this violence. Witnessing someone slaughtered because of religious rage changed me. I have tried, and failed, multiple times to write about it. I took a Visual Culture and Religion class a couple of years ago, and for my final project, I drew a picture of what I saw and made a video narration of my experience. It messed me up. I still can’t write about it. Drawing it was possible. I had vague ideas of adapting my presentation for the public and sharing it somewhere but I do not have the fortitude to work on it. Maybe someday I will, maybe not. It happened over thirty years ago but I am still haunted by it. And I know I will be haunted until I share it.

Fox: Thanks so much for sharing all these stories and ideas with us, Saumya! You’ve given me so much to think about. In closing, I’d like to ask what writing (and/or other) projects are you working on now that you’re especially excited about?

Saumya: In 2013 one of my horses accidentally head-butted me, causing a Traumatic Brain Injury. It has altered my life. My symptoms make writing a challenge, so I’ve turned my attention towards drawing and sculpture. I’m very excited to see what emerges from that!