Letter One

Dear Continuum:

I got an issue of Poets and Writers in the mail yesterday. I enjoyed what I read, but it was not inspiring at all. It was realistic. It was honest about the uphill battle it is to get a book seen. I know the work of this all too well. But this letter is not about books, this is about voice and the love and armor you will need to have yours heard.

When I think about being a writer in 2015, being a writer with a Black woman’s voice— as Lucille Clifton said, “I am a black woman poet…and I sound like one”—with no agent, no powerful mentor opening doors, no financial support, no salary, no benefits, then I realize that this really is a crazy path. Deciding to be a writer was beautiful. Writing is beautiful. Deciding that my concerns, dreams, hopes, and voice are valid, and committing myself to putting my visions on paper has been a deeply healing experience. This work connects me to people I have never set my eyes on. However, being a writer in a country that does not support art and writing from the heart of my Black woman mama mouth is a struggle that sometimes leaves me speechless. (But the point is to exhaust me/us beyond words, isn’t it? So I rest up and speak on) Beloved, this landscape is actually more treacherous now than when I started 19 years ago. I don’t say this to discourage you, I say this because you need to know that you are embarking on the path of most resistance; if you plan to walk it, you need to study and you need to endure.

Listen, there is all sorts of color in academic conferences and departments now. Much of that writing is non-threatening and status quo. It’s the type of work that could have come from 18th-century nowhere. It’s work that no one in our communities or families could wrap around cold shoulders or grasp onto in desperate moments or even nod at in faint recognition. That, we are constantly being told, is poetry. That exsanguinated verse. But you and I both know poetry can be soulful, grounded, gravity-defying and irrepressible. If your poems walk picket lines, work in soup kitchens, gather dandelion leaves, sweat, jump rope, wear stilettos, shout, give birth, watch the phases of the moon, or know that it is appropriate to put flowers in the ocean on New Year’s Eve and pour liquor on the earth before anyone living takes a sip, then supposedly they are not poems. Supposedly you missed the memo on craft and your poems will be returned to sender. Save your postage. Honor your time.

Tap your cimarron blood, tap the defiant DNA that gives your hair such good posture. Find a community of poets dedicated to writing and walking and being liberation. Study Hughes, Baldwin, Hurston, Walker, Shange, Baraka, Hayden, Dumas, Bandele, Johnson, Girmay, Moore, Rux, Hammad, Rich, Clifton, Boyce-Taylor, Brooks, Madhubuti, Medina, Forche, Ya Salaam, Rojas, Rivera, Knight, Esteves, Kaliba, Simmons, Kaufman,Sanchez, Finney, Perdomo, Espada, Betts. This is your work and there are so many more to study; you will find them as you make your way. Read, write, edit and find a way–let the poems find their way–get those words read and heard. Find someone unbought to publish your stuff. Be really brave and publish the work yourself, but don’t stop there. Publish the poets around you who stand on the frontlines and refuse to bow down. Publish those mamas bringing their babies to readings, those poets whose works are in anthologies that they read in the food stamp office, those lettered poets who can’t make the rent, those poets with a day job who organize free workshops and salons, those poets who never lose their accents, the ones cast off in a spoken-word ghetto because they actually dare to connect with an audience. Publish all of them, who are all of us, who fight this fight because we are determined to keep the doors open for the next generation, and because we would go crazy without our tongues, without our pens braiding the strands of our thoughts into some type of beauty. Not pressing our voices flat. Flat to that white rageless whisper. Not doing that and paying a heavy price.

And so it is.

One,

Mariahadessa

Letter Thirteen

Dear Continuum:

I hope this card finds you in great health and strong spirits. Yes, there has been a whole lot going on lately, and I’m glad to see it too! It’s about time people went out into the streets to make their voices heard. It’s way overdue.

What have I been doing? Maybe I have been feeling more than doing this time around. After this last incident, I sat quietly for days trying to figure out what to do. Not just with my body or my words, but what to do with my rage. The rage I felt was so big it startled me. Flattened me even. I knew I couldn’t be as effective as I wanted to be in that state. So I sat quietly. I called friends. I went to see an art exhibit. I wrote “Black Lives Matter” in sidewalk chalk on the streets. You see, we’ve been in the streets before. I am not an old lady, but I’ve been protesting one thing or another since I was 16. My first protest was outside of a courtroom in Brooklyn, and since then I’ve been at marches to prevent invasions, end wars, demand an end to police brutality, stand in solidarity with the Zapatistas, and insist that the killers of our children, grandmothers, brothers and sisters and lovers at least be arrested for their crimes. And so, initially, I stayed still because history seemed to be repeating itself and I was wondering if being in the streets was going to achieve any goal whatsoever. I thought about Apartheid and the petitions I’d signed, and the products I refused to use or buy because the companies were invested in South Africa and thereby supporting apartheid. I thought about things I had not seen—like the bus boycott in Montgomery. I know pulling money out of the system is an extremely effective way to make a statement heard. I started studying the armed resistance in Mississippi. Members of my own family used arms to defend themselves against racists in the South when it was necessary, and I thought it was important to research how effective that strategy had been. But more than anything else, I thought about what art could do. And I saw what art could do. I was at a temporary loss for words but when I danced, I felt a lot better. When I sang, I felt a lot better. When I saw visual art, I felt a lot better. My friend Cheryl read me the poem “Power” by Audre Lorde and it helped dislodge something in me. But I was still thinking about my poetry. What could it do really do when 12 year olds are being shot down by police on playgrounds, and 28 year-olds are being killed “accidentally” in stairways, and children’s bodies are being left in the streets and no one is being held accountable? What the hell use is a poem then? I finally came to this: while poetry may not win the battle, it can move people to understand why the battle is necessary. It can help people decide to get involved.

I read a poem about rape to an audience of college students recently. During the Q&A a young man raised his hand and said that he had sat through a training on preventing sexual harassment and assault in the military, but it had not affected him the way the poem had. He said a poem I’d shared about a particular incident in Mississippi illuminated the devastation of racism. He said no seminar or training had shown him these things the way that the poems had. That is the power of art.

The other powerful thing about poetry is that it helps people to envision another world, a better one. And that is a huge gift when you’re in the midst of struggle or despair. Remember music and poetry helped soothe and strengthen people who were on the frontlines of struggles globally. Sometimes the poets and musicians were on the frontlines.

A lot of people share their poetry when these painful events unfold and that is understandable, but I think we have to be conscious of what we do with the art that comes from tragedy. If I can, I like to use art strategically to raise awareness about an issue and move people to action. Sometimes the actions are small ones like signing petitions or bigger ones like donating resources (time, money, skills) to relevant organizations. In some cases having readings to raise money for the families of the victims might be useful. We can also organize ourselves as artists and work collectively to support groups we believe in. It’s also important to me that the work I do be in the hands of people who can use it in practical ways. I’m excited when poems are used to facilitate discussions, or trainings, or healing sessions. When it comes to doing this work, it’s our job to know the difference between exploring tragedy in a useful way and exploiting it to bring attention to our own work and ourselves.

These are some of the reasons I sat and considered what I was going to do very carefully.

In the end, of course, I went out into the streets, and I signed online petitions, and I donated what I could where I could. I’ll find a way to make what I write useful. And I know you will too. Just make sure you take good care of yourself in the midst of all this. If you want to keep doing the work, you have to be as healthy and as centered as you possibly can be. We need you for the long haul. Be well!

Pa’lante.

Love,

Mariahadessa

Letter Seventeen

Dear Continuum:

I hope all is well. Forgive me for taking so long to write you. Between traveling, editing poems, finishing my next book, writing, teaching, being present for my daughters a lot of things get neglected. I miss staring at the sky, hanging out all night with friends, long phone conversations, dance classes and painting. I realize that I need to do all those things again. They feed me and my writing. I did tell you that our very lives are art, and I stand by that even if I don’t always exemplify it.

Art goes beyond our pens and paper. Art is our very way of thinking and breathing. I don’t have days or weeks of silence, but regular mental rest is critical for me. I go to my favorite restaurant every few weeks to get space to explore, wonder, and just be. Somewhere I read that “we are human beings not human doings.” Being can happen in unexpected places like an airport or a crowded subway. It’s where I can have access to my own thoughts; it’s unhurried space. My art—when it comes from a space of being—is deeper, more complex and layered than that which comes from a whirlwind.

Anyway, I can imagine the pressure you feel with your work and the options you’re weighing. Things are so different now, and if there weren’t others who inhabited that 90’s poetry space with me, I’d think I dreamt it all up. Back in the day no one in my circle– or its orbit– ever asked me where I got my MFA. No one. No one asked me what organization or institution I was affiliated with either. When I started sharing my work, poetry was about poetry, and community and not about pedigree. I miss that. It felt like every moment was an apprenticeship to word, to color, to struggle, to sound, to movement and ideas, and love; I learned to spend more time with elders. Be quiet. Listen. That’s where I think this writing thing really starts. Listen. Listen with your entire body and being.

So should you get an MFA or a PhD? Sure if you want to learn, and certainly if you want to teach. But there are many unemployed and underemployed folks out there with degrees. Nothing is guaranteed. And if you go that route, just remember to keep opening doors for the folks coming behind you.

I’ve seen some people treat poetry as a corporate ladder to climb. I’ve watched from the sidelines as people climb rungs made up of other poets’ backs. There at the top are the prizes, your name in lights, the book deals. I’ve seen it, and you probably see it too. There’s a whole lotta inside deals going on too. That is not the only way, but it’s the dominant way. You’ll know who operates by it. When they realize you can’t do anything for them, they back away quickly.

Remember, there is another way. It’s as ancient as we are. It won’t cost you your soul. It won’t alienate you from your Grandma. It might even make your work meaningful to her.

I got an MFA from a place no one really knows. I wanted to learn more about writing while being in the Bay Area. I wanted to have more options than I did with a Bachelor’s degree. I know people are making it work without advanced degrees, but I couldn’t. I know some folk who are making it work without any degrees at all. You ask what I’d do? I’d give myself space to decide what is true for me.

Everyone’s path is different, Continuum. Keep walking yours, and stay connected to your heart.

Love,

Mariahadessa

[Letter One originally appeared at the Her Kind section of the VIDA website, and appears here by the author’s kind permission.]

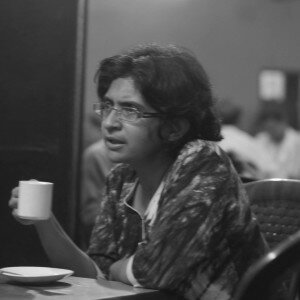

is the author of Karma’s Footsteps (flipped eye). She is the poetry editor of the literary magazine African Voices. Her poetry has been the subject of a short film “I Leave My Colors Everywhere” and it has been published in BOMB, Crab Orchard Review, North American Review, WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly, & Black Renaissance Noire. Tallie is also the mother of two wild, wonder-filled daughters. Her most recent book, , is now available from Grand Concourse Press.

Photo Credit: Dominique Sindayiganza