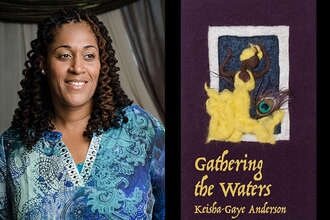

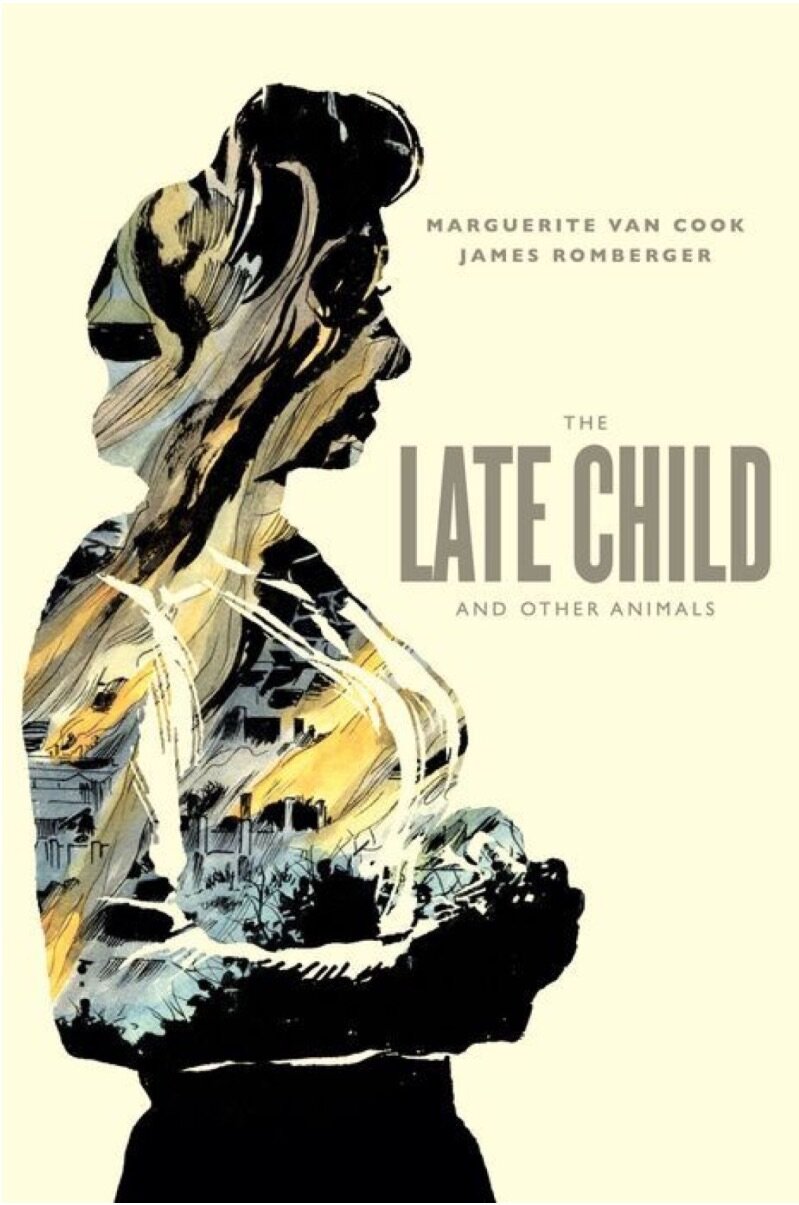

Editor’s Note: Marguerite Van Cook and James Romberger are the artists whose collaborative graphic novel, Late Child (Fantagraphics Books, 2014), tells the intimate, autobiographical story of the struggles Van Cook and her mother faced during World War II and after, as Van Cook, a child born out of wedlock, came of age and learned how to seize her own voice and power in an aggressively sexist and classist society. Alex Dueben interviews them here about the stories ehind the book, and their processes and conversations in creating it.

Exploring the Personal and Political Landscape of The Late Child and Other Animals

by Alex Dueben

The new book The Late Child and Other Animals opens at the height of World War II with the co-author’s mother and aunt on top of Portsdown Hill, watching the city of Portsmouth burn. That haunting and beautiful image sets the tone for the book. The Nazi bombardment of the city and the war ended by 1945, but the scale of destruction and devastation that the city–and so much of England and Europe–endured would shape the decades that followed. This book is a very personal story of Marguerite Van Cook and her mother, but it is also a story of these societal changes and the shifts in consciousness that accompanied them.

Sitting in a restaurant on the Lower East Side of Manhattan over coffee, Van Cook is still a little overwhelmed reflecting on it all. “The war didn’t end in 1945,” she said.

“For years, nobody had anything to eat. When I was a kid, I played in bomb sites. There would be the remains of somebody’s kitchen which was half there. The pots and pans were still there. Over behind our house were giant chains from the ships’ anchors. A friend of mine lived right next to a junkyard and in the middle of it was a diving bell. You wouldn’t know there was a diving bell unless you climbed down over all this scrap metal to get in there. As little kids we would go and have a club in there.”

The book consists of five stories involving Van Cook or her mother and what’s striking about the book is the way that Van Cook and James Romberger have managed to tell a series of precise, personal stories, the subtext of which is the vast societal changes that happened during those years and would follow them. It’s a beautiful book, but at its heart is unease. Van Cook was born out of wedlock and the way that she and her mother were treated is a chilling and sad.

Work on the book began when Van Cook took a writing class while studying at Columbia. “I felt my mother’s story was important to tell and that the issue of ‘illegitimate’ birth doesn’t get much attention. When you start to read novels and look historically at plot lines and even now when you turn on the television, the murder is so often committed because someone is covering up an illegitimate birth. It falls onto the child. I thought it was important to start to work with that.

“My mother was upset a lot of the time,” Van Cook. “She would talk to me about these things when I was much too young to really understand what was going on. She would repeat her stories. I was still carrying around her voice in my head. When it came to writing down what she had to say, I could hear her. I was still hearing what she said. The dialogue is authentic to my mother and then to some degree having grown up in England and knowing the sorts of questions that they ask you in these weird different situations I was easily able to extrapolate and add to what she’d told me and fill in the blanks.”

Perhaps the most shocking story in the book is “Nature Lessons,” which features a young Van Cook walking home from ballet class at night and a man who followed her. The man’s voice is vivid, which for her was because she’s had that voice and his words in her memory for decades so clearly. At the very end of the story, she also writes about how as an adult she understands why her mother didn’t go to the police and try to find the man.

“At the time it was really difficult for me because I didn’t know what happened,” Van Cook said, “things went unsaid a lot of the time. I spent a lot of years trying to figure it out. It was traumatic for me. As I got older–and then when you have your own child–you start to understand little bits and pieces. As an adult, it was interesting to go back and look at my mother’s narrative.”

“I thought we could have ended the book on that chapter,” Romberger said. “The ending was the perfect set up for another book when she becomes a punk. ‘I’m going to sing as loud as I want and nobody’s going to tell me what to do.’

“When I first met Marguerite she was always talking about the issues that come up in this book,” Romberger said. “The way she was treated when she was in school for being illegitimate profoundly affected the way she approached everything in life. To me, if anything’s worth doing, this is an issue worth doing. This idea that people can be treated as less-than because their parents aren’t married.

“Look at the plot of every Jane Austen or Dickens novel,” Romberger said. “We were just watching ‘House of Cards.’ In almost every show there’s an illegitimate child that’s kept secret and still it’s the major plot point for every single goddamn story. It is continuing to be the major story. Why is this the one thing that is perfectly acceptable to be prejudiced against a child?”

“I was a bright kid. I had won a place to an English public school. The headmistress at my school called them and got my scholarship revoked. She used to hit me often. I was told ‘you’re a dirty filthy girl.’ It was taken out on me. Meanwhile, I was getting 100% on my tests,” Van Cook said. “It was not just sticks and stones.

“One of the things I say in the book–which I didn’t know until I wrote it–after that chap tried to take me away and I was still going to school, I started singing really loudly when I was by myself on the street. Fast forward twenty years or whatever and there I am singing on stage in a punk band opening for The Clash.”

“I’ve never read anybody writing about not just going to concerts, but about being right there in the room, being in that environment, touring with The Clash,” Romberger said.

“There was a lot of driving around in vans,” Van Cook said with a laugh.

Van Cook wasn’t just a punk. She was the singer and co-founder of the band The Innocents, which among other things, toured the UK in 1978 with The Clash and The Slits, where they performed 31 concerts in 32 days as part of The Clash’s Sort It Out Tour.

“At some point I will write about my time in the punk world,” Van Cook said. “Punk has its own energy and I suppose the book might benefit from the urgent approach that was the hallmark of that time. It was a truly exhilarating time.

“I did just get a studio tape of The Innocents which we had recorded with Dave Goodman, who recorded the Sex Pistols,” Van Cook said. The band recorded one album, which though it was never released, was produced and engineered by Goodman who worked on the Sex Pistols recordings. “Terry Smith, our last drummer saved it from oblivion. We had lost touch, he was in Australia and we only recently found each other. I definitely plan to do something with it. It has some of the songs we did on The Clash tour.”

By tying the book’s stories together the way she does, opening with the devastation of World War II, and ending in the summer of 1968 in France, Van Cook makes the unspoken subject of the book the period of austerity that defined British life in the postwar era and played a significant role in shaping the punk movement and her generation.

“People don’t really get that we had no new clothes to speak of. They had to darn everything during the war. Everything was precious and when they decided to buy clothes in the postwar years, every piece was an acquisition. When I went home and took a jacket–that was perfectly good–and cut it up with a pair of scissors, it was a slap in the face, far worse than swearing in public. That war generation valued what they had done for us differently.

“For me, the Paris cultural uprising of ’68 was pivotal, and I don’t say too much about it in this story. As I say in the book, we were too young. But I saw it. I was starting to become radicalized. It was the other way of being. The war and ’68 bookended things for me.

“Many writers want to create something beautiful, but they also want to present their difficulties. The challenge is to show something of yourself and to upend a set of paradigms about who you are or what that means. I wanted to show that I came into the world with a beautiful soul and hopefully I’ll leave the world with a beautiful soul–although it’s been a little corrupted,” Van Cook said laughing.

“I’m getting my PhD in French Lit at the moment and I thought, well, I’ll end this first narrative in France, where I had another lesson in growing up. I thought that people had done everything they could possibly do to me–I don’t just go through a litany in the book–but now they’re going to kill my rabbit and feed it to me?” she asked laughing and swearing. “My girlfriend wrote to me from England and said ‘I remember that you were really traumatized by that.’ Her mother was a very repressive figure and she represented that whole world to me so I was going to eat that rabbit. I would not give her the satisfaction of weakness. But truthfully, I didn’t really like the mean rabbit anyway.”

2.

“We were sitting at the bar and James said, ‘oh, I do comics.’ I said, ‘I really like Jack Kirby,’” Van Cook remembered, “and well, that was that.”

“We were talking about Jack Kirby and Vaughn Bode,” Romberger said.

“That was the first conversation we ever had,” Van Cook said.

The book that made their reputation was “7 Miles a Second” which they did in collaboration with their friend, the artist David Wojnarowicz. The book was originally published by Vertigo in 1996, but the two had been collaborating for many years before that. During the 1980’s, they were known for running the art gallery Ground Zero on the Lower East Side, and for their comic strip, also named “Ground Zero.”

“Ground Zero began as a semi-autobiographical, science fiction serial strip made with the specific intention of subverting and exposing as many tropes of comics as possible while still telling a story,” Van Cook said. “It is self-reflexive and irreverent. The characters often leave the frame and move around the page. We wanted the comic process to be a two-way street, where the reader has as much work to do as us the artists. My character, The Unit, gave us the chance to create a strong female character at a time when there were for the most part only vacuous depictions of women in comics.”

“We will eventually finish and collect it–it will make quite an interesting package, because so many of the strips were drawn to be printed in so many different formats: newsprint tabloids, small and large-format black and white alternative and literary zines, slick color magazines,” James said.

“We were so underground on our first thing that we did together–we decided that we wanted to be really deconstructive about it, so we decided it wouldn’t appear in a magazine consecutively,” Van Cook said.

“Before I met Marguerite I’d done a few things for Marvel, for Epic. Then I started working for ‘World War 3 Illustrated,’ which is much more alternative. I really wasn’t looking to be a commercial comics artist. I started ‘7 Miles a Second’ with David in 1986. It took me like ten years to finish that book.

“‘7 Miles a Second’ went through a bunch of rejections,” Romberger said. “I gave a dummy of it to [the late Vertigo editor] Lou Stathis and it kicked around the offices there. They said there’s no way in hell they were going to print this thing. After David died and we finished the book, we had a show of the originals at PPOW gallery. The people at Exit Art were friends with Jeanette Kahn who was the head of DC and they sent her over there. She said ‘this is awesome,’ went to Karen Berger and said, ‘do this book.’ Then we did a few other things for Vertigo. Axel Alonso was our editor there, but he left and went to Marvel.

“After that, we went through proposal hell up at Vertigo for five or six years,” Romberger said. “We put together a bunch of concepts and I, and we, did samples for all these books and nothing. None of it got published.”

“We did so much unseen stuff for them, it’s ridiculous,” Van Cook said.

“We also did a little fanzine called ‘Comic Art Forum.’ We did three issues. It was a really small scale thing but it was a nice thing. I interviewed Gene Colan. We did an article about Kirby and the CIA use of that Lord of Light proposal. I met Jim Steranko. I’d always liked his work since I was a kid. I still have this interview with him, it’s still unpublished, we went through every single thing he did. We got along really well and at a certain point he goes, ‘why haven’t I heard anything about you? I don’t understand why I don’t know your name.’ He said, ‘what you have to do is go in and do some mainstream work and be an artist-warrior and get your name out there.’ I was leaving the MoCCA convention around 2004 or so and I ran into Karen Berger, the head of Vertigo. She said, ‘oh, what are you doing?’ I said I just got accepted at Columbia University. She said, ‘you’ve got to give me a call, I might have work for you.’ Of course! Because if you’re busy as hell, let’s give you more to do.

“Next thing you know I’m drawing ‘The Bronx Kill’ which isn’t something I’d normally want to do. I’m the guy who drew cops beating the hell out of everybody in ‘World War 3!’ They figured out this to torture me? Then they sent me this script for ‘Aaron and Ahmed’ and I was like, I’ll do that. I did those two books but I was unhappy with the result. I was like, that’s it. No more corporate comics.

“I did a thing for the last issue of ‘Mome’ because I finally sent some stuff to Eric Reynolds at Fantagraphics. Then I sent him ‘7 Miles a Second’ and I said, maybe you guys would be interested in this? Apparently they’d never seen it. I always wondered why they never reviewed it. It was because nobody ever sent it to them. I did ‘Post York’ for Tom [Kaczynski’s Uncivilized Books]. He was interested to see it and this is how it came out. Now it’s like this downgrade. I mean Fantagraphics is great, but recently I did a comic for the ‘Study Group Magazine’ and then a minicomic. We’re reverse engineering our careers down to working for free,” Romberger laughed. “But I’m much happier because this stuff is coming out the way I want it. I’m working with people I like. I’m in the zone. I think this part of comics is much more vital, much more energized and much better work is coming out, because the companies with those corporate character/properties, it’s almost impossible to do anything of value in their formats. Image is also slick and commercial but they’re creator owned. That’s the difference. There are books there I like quite a lot.

“I think comics is a vital industry right now, but a lot of people aren’t getting paid. The readership is pretty small but they’re faithful. A lot of times the readership is your fellow artists. It’s a strange scene to be in, but it’s also the last bastion of book publishing in a sense. These books that are coming out are some of the most beautiful books ever made.”

“Back when we started, we had to go and pay somebody five dollars to typeset on a computer,” Van Cook said. “We did hand-cut color separations for some of our comics. It was a lot of work. Now people can do what they want digitally and it looks exactly how you want. I can’t imagine trying to get the production values we have on this book then. You couldn’t have what you wanted, so you would go make it yourself. So now finally we can have the work how we want it.

“There’s an impulse James and I have shared over the years of making art that is transient,” Van Cook said. “We’ll put in on the street, we’ll make it on newsprint so it’s not going to survive past its moment.”

“We did it deliberately,” Romberger said. “We kinda screwed ourselves doing it though. It made sure to limit our audience. It was a punk aesthetic. Forget posterity. We’re in this moment and that’s what you’re doing it for.”

“The idea of a daily comic was one of the starting points that we came from,” Van Cook said. “It comes out and is gone. It isn’t held in this weird reverential place. It was a radical thing that we’re not ready to give up, though certainly we love this book.”

3.

“I’ve been on the record ragging about the current treatment of writers as opposed to artists in collaboration,” Romberger said. A noted critic, Romberger is one of many people who have been critical of the contemporary tendency to look at comics through the lens of writers or with a literary eye that considers the art and the artist to be a secondary or incidental concern.

“A lot of times in alternative comics it’s about the auteur and I tend to think that it’s an extraordinary combination for someone to be able to write and draw well. It’s hard and it’s very time consuming. I think having writers work with artists expands the possibilities of content and so there are possibilities of interesting collaborations,” Romberger said. “People from outside must think cartoonists are all narcissistic. What are you going to do? You have to do what you know well. You know yourself with any luck–or at least that gives you something to work with. Unless you’re somebody like Joe Sacco doing actual journalism or somebody who’s actually going out and referencing this stuff so exactingly, because you have to impart this believability to the reader or it’s not going to resonate with them.”

“Going back to the point about collaboration and auteurs, I think it’s too much,” Van Cook said. “It’s too much to do everything and why would you? Because then you wind up with a book that’s about being in a coffeeshop as opposed to a book that’s about traveling the world, jumping out of airplanes, whatever else is interesting.”

“But whoever draws the book would have to know what the airplane is like, what’s the landscape from above look like,” Romberger said.

“Only one of us is jumping out of the airplane,” Van Cook said.

“You jumped out of the airplane, but I have to go and redo the damn jump in order to know how to draw it,” Romberger said. “It’s a very tangible thing. You have to know what it’s like.”

“It’s an interesting thing to work with somebody else and having the ego thing going on,” Van Cook said. “Kudos to him. He lets me go crazy on top of his inks.”

The two have a habit of bantering back and forth in the way that couples who have long been comfortable with each other often do. This back and forth also represents the way that they worked on this book, with Van Cook writing it, Romberger adapting and drawing it, and Van Cook coloring his inked pages.

“There were places where you went, ‘you got that wrong’ and I was resistant,” Romberger said. At the beginning of the France chapter in Paris, you were like ‘no, this is wrong.’ I fought because I’d already pencilled it and our time frame was really tight but she was right. It was a lot better. I went back and redid the pencils, but it was painful to redo because I liked those compositions.”

“I did those potboilers for DC, but I found that very frustrating. Even if it seemed like a good idea in proposal form, by the time it went through their editorial process with so many people weighing in, I lost control. I don’t particularly like digital coloring. I want my hand on the thing. It’s an illuminated document. This book here is perfect. It’s exactly the way we wanted it. With Fantagraphics we can get exactly what we want. They’re very attentive to what your needs and wants are. These other guys are paying you a page rate, which is great, but you have no control. I couldn’t say, I want to color the book myself. I had to audition for my own book and have someone say, ‘you’re not suitable.’ To me instead of getting the page rate I’d rather have something I’m proud of.”

Romberger has had a busy few years, and it’s clear that he sees his work from the past few years as the best of his career. He drew a comic for the final issue of “Mome” which Romberger also colored. He wrote and drew “Post York” which was published by Uncivilized Books. Fantagraphics released a new larger edition of “7 Miles a Second” in hardcover with Van Cook’s original colors. Last year Oily Comics released “Daddy” a short comic Romberger made with Josh Simmons (“The Furry Trap”) and the recent volume “World War 3 Illustrated: 1979-2014,” which collected some of the major highlights of the magazine’s 35 year run, includes Romberger’s early story “Jesus in Hell” which appears in full color for the first time.

Romberger mentioned that his current project is another “Post York” volume, a collection of “Ground Zero” and he hopes to draw another book with Van Cook, this time about her years as a punk. Van Cook made it clear that she wants to tell those stories of her youth, but this book is as much about her mother as it her, and she wanted to create a book that would in part serve as a tribute to her.

“My mother was a printer during the war. She won prizes for casting on hot metal type. Getting the letters on in speed for setting up newspapers. My mother won awards for that, which is this big union job, but after the war the guys came back and she was out of job. I have a deep respect for printing and media and newsprint,” Van Cook said with a smile. “It’s in the family, if you will.”