During 2016, the Spotlight Series focuses on two poets per month whose work and consciousness move us, challenge us, inspire us. This month’s second poet is Cam Awkward-Rich.

Fox Frazier-Foley: Talk to me about the core of your creative drive and the expression it finds through poetry. There are lots of ways to be creative in this world—what motivates you to write poems, specifically? Additionally, what motivates you to navigate the poebiz landscape?

Cameron Awkward-Rich: Well, I’ll answer in reverse: I don’t know if I do navigate the “poebiz landscape.” Obviously I must, but it feels pretty unintentional, almost exactly like standing in the corner of a party full of people who are unbearably too brilliant and too beautiful (or just unbearable), but this party is where all of your friends are so you’re there too, standing in the corner hoping no one will notice you though of course they will because you’re a) being weird, over there alone and b) wearing that one outfit that makes you feel pretty. I’d like to say that I’m motivated to put my work out there because I really do believe that art both marks and expands the boundaries of what is possible to know/think/imagine and when I was growing up it would have been nice to have evidence that someone like me existed, that I could be thought. Of course that’s true. But, also, poetry is where most of my dearest friends live, so I live there too.

I think the first part of this question boils down to why poetry? It’s probably not enough to say that I have terrible visual aesthetic sense, yeah? Terrible fashion, terrible hand-eye coordination, terrible. But I’ve always known how to work with language. In part, it’s because I’m terribly anxious, so almost anytime I speak coherently, you can be sure whatever I’m saying has already been composed, crafted. Even before I started “writing,” then, I’d had a lot of practice. Also, I’m learning that poetry is not necessarily my medium. Essays (lyric, standard academic, etc.) are really my jam. What a poem can do better than an essay, though, is appeal to different registers of sense, both as in sensory info and as in making sense. Poems let us communicate/understand things (feelings, ideas, experiences) that don’t make sense as if they did.[1] And, honestly, as someone who finds the world, my self, and others utterly bewildering, I need all the help I can get when it comes to making sense.

FFF: What are your influences—creatively (esp in terms of other media/other art), personally, and socially/politically?

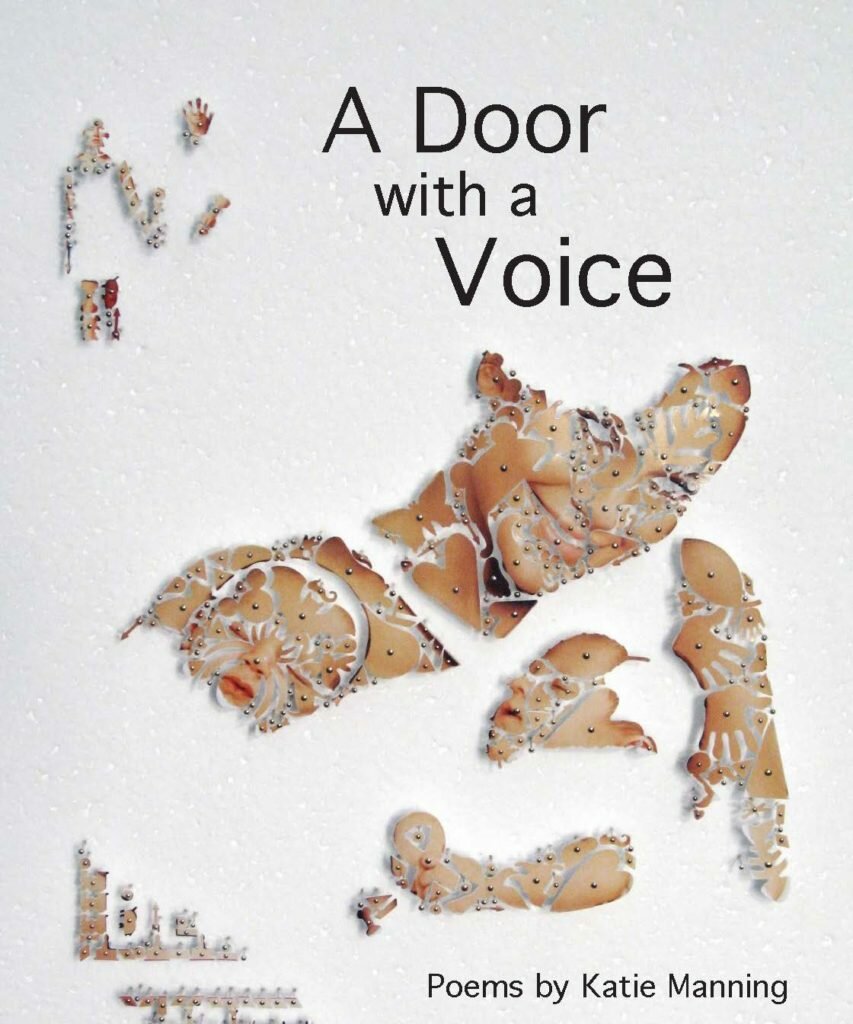

CAR: To avoid making a long, nonsense list, I’ll say that I’m sort of a sponge: I read too much and watch too much and am too easily pulled in the direction of whatever I am currently consuming. That said, the things that I am most inspired by and am trying (and failing) to align myself with (creatively, personally, and politically) tend to be by femme and/or queer poc whose work turns away from the imperative to “humanize” (i.e. make legibly human according to the logic we’ve inherited) poc/queer life and instead engages the awkwardness, violence, persistent strangeness produced by that very endeavor. There are, in particular, visual artists working in collage (Alexandria Smith, who generously provided the cover art for my book, and Wangechi Mutu are two of my favorites), poets (Francine J. Harris and Ronaldo V. Wilson are two contemporary touchstones), and speculative fiction writers (Larissa Lai, Octavia Butler, etc) whose work has helped me think about how I’d like my life/work/politics to align. That said, my poetry actually operates mostly in the confessional mode, which I think is also an important mode and has been personally necessary for me at this particular moment in my life.

(The abbreviated nonsense list goes, in addition: my friends/peers in this weird house party, soap operas, movies that take place in tightly bounded worlds (i.e. spaceships, underground colonies, single buildings), my sister, other trans writers, my cat, academics who manage to navigate the academy without becoming creatively/intellectually/politically diminished, old ladies who don’t give a fuck, theory that delights in witticisms, people who ride the same bus and/or train every day, devastating novels.)

FFF: Describe your aesthetic as a poet. What do you value? What do you try to do with/in your work? What, to you, makes cool art/literature? What’s most important for you in a poem, or in a book of poems—as author and as reader?

CAR: Oh, all kinds of things. Anytime I come away from a book/poem knowing the world differently somehow. Anytime a phrase or an image gets stuck in my head like a song. Anytime an aesthetic object makes me react viscerally, moves me to laugh or (less frequently) cry or throw it across the room. As a reader, any of these marks an object’s success, so, as a writer, my work’s capacity to affect others in similar ways is how I measure my own success.

Also I suppose I should say that there is plenty of art that moves me in ways I’d rather not be moved: to feel, again, the persistence of white(cisheteromale) supremacy. There’s always the question of whether something can be “good” art despite being rooted in, reinforcing, and/or coming from someone whose actions perpetuate various oppressive ideologies. It’s a hard question, I think. Because one wants (I want) to say no, but then one inevitably cannot help but be moved by, even enjoy, problematic objects, as all objects inevitably reveal themselves to be. So while I want to say that the most important thing for me in my work and the work of others is this political dimension—does this object help me to imagine other worlds?/give me respite from this one?/expose or rework its harms rather than perpetuate them?—I also think that everything I write and most things other people write fail at this in one way or another. Still, in the attempt to not fail, new possibilities open. Which is the difference: art that moves me to feel white supremacy again might actually be incredibly “good,” or at least successful, art. But it lacks the surprise, the challenge, the freshness of work that actively tries to do something else. Cuz what’s less surprising than racism, ableism, misogyny, transphobia, etc?

FFF: Tell me, if you’re willing, about something—an experience, a piece of art, anything really—that has fundamentally moved and/or shaped you as a person. What was the experience? What was it like? How did it shape you as an artist/poet?

CAR: During my senior year of college, both of my mother’s parents died in pretty rapid succession. I feel weird saying that their deaths altered my writing style for the better, but retrospectively I think it’s true. I never felt very close to my grandparents for all of the usual reasons: being a petulant adolescent, differences in religion, being obviously queer and always wary about what that might mean they thought of me. Anyway. After they were gone, I discovered a glut of speech, things I’d never said but should have or wanted to, questions I’d never asked.

Throughout college, my writing—but especially the writing that I thought of as Poetry—wasn’t really aimed at communication. It was confessional, sometimes, but I didn’t really think about the reader. Often I’d think of a poem as a little puzzle, not a speech act. But I found myself wanting to talk to my grandparents, so I wrote my first poem that was intended to be performed. It was straightforward and sentimental and cheesy. But it moved people, people who’d never known my grandparents and people who loved them dearly. And that’s, initially, how I found my way into the world of slam and spoken word, how I started valuing a poem’s capacity to affect, and why I started writing poems in my own, ordinary voice.

FFF: Name a book or two that you think everyone should read, and tell us a little bit about what makes it/them so mind-blowingly awesome.

CAR: A book or two?! What do you think I am? That’s way too much pressure, so I’ll say that a book that I’ve been thinking with a lot lately is Eli Clare’s Exile & Pride: Disability, Queerness, & Liberation, which was out of print for a sec, but Duke University Press just reissued. It’s a wonderful example of the hybrid criticism/memoir genre and also, sadly, still feels ahead of the times (even though it was first published in 1999) when it comes to thinking gender, sexuality, ability, class, and, to a lesser extent, race together. Clare asks hard questions that today we seem hesitant to ask, let alone approach the answers to. It also manages to be a great intro text for people not already thinking about disability justice, in particular. Also it’s beautifully written.

FFF: Anything you want to talk about pertaining to your art/craft/literary or writing life that I didn’t ask?

CAR: Not necessarily. Though last time I appealed for help in an interview it worked out pretty well for me, so I’m going to do it again. I’ve been feeling pretty stuck lately, in terms of writing, and have been looking for books that will unstick me. Not like self-help books, but like novels so devastating or critical theory so gorgeously absurd or movies so strange they’ll shake me out of it. Anyone have suggestions? Hm?

[1] Taken from Jonathan Culler Theory of the Lyric page 184: “In a wonderful book, Precious Nonsense, now largely neglected, Stephen Booth uses the example of nursery rhymes to illustrate poems’ ability to let us understand something that does not make sense as if it did make sense. We seem to take pleasure in accepting nonsense…”

Cameron Awkward-Rich is the author of Sympathetic Little Monster (Ricochet Editions, 2016) and the chapbook Transit (Button Poetry, 2015). A Cave Canem fellow and poetry editor for Muzzle Magazine, their poems have appeared/are forthcoming in The Journal, The Offing, Vinyl, Nepantla, Indiana Review, and elsewhere. Cam is currently a doctoral candidate in Modern Thought & Literature at Stanford University and has essays forthcoming in Science Fiction Studies and Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society.