(an excerpt from ‘Comics Poetry: Beyond Sequential Boundaries’)

Can one see, indeed, that a painter or a poet never starts a painting or a poem before they have been carried to see it more or less by their spirit, in its simultaneity of principle elements…? ~ Rodolphe Töpffer, Réflexions et menus propos d’un peintre genevois

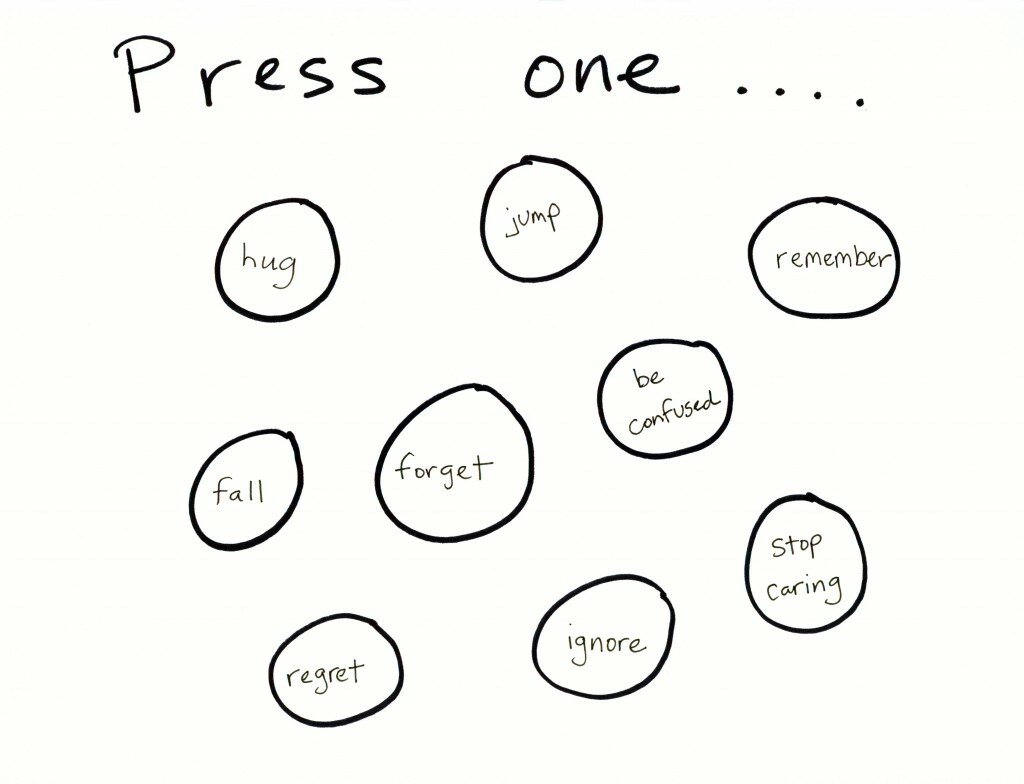

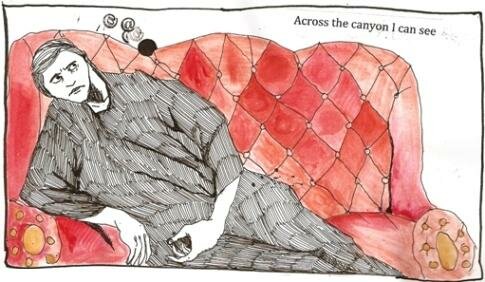

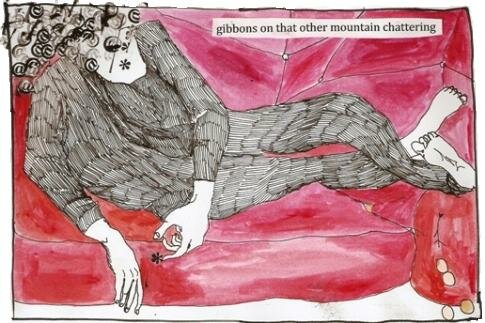

Finding connections between comics and poetry has been my focus for a few years now. It’s an interest shared with a field of talented creators including Matt Madden, Warren Craghead, Bianca Stone, Paul K. Tunis, Alexander Rothman, Derik Badman, Summer Browning, Michael Farrell, Eryon Franklin, Franklin Einspruch and Julie Delporte, to name too few. Given this growing commitment to comics and poetry, (evident in recent , , and ), this article discusses comics theory, its relevance to experimental forms and possibilities for the future of comics poetry.

Existing comics research often borrows concepts from narrative theory, film and cultural studies as well as visual communication. But such comparisons have been criticised by various comics creators, like Gregory Gallant (a.k.a Seth), as increasingly inadequate. Seth argues

Comics are often referred to in reference to film and prose — neither seems that appropriate to me. The poetry connection is more appropriate because of both the condensing of words and the emphasis on rhythm. Film and prose use these methods as well, but not in such a condensed and controlled manner. Comic book artists have for a long time connected themselves to film, but in doing so have reduced their art to being merely a ‘storyboard’ approach (Seth, 2006, 19).

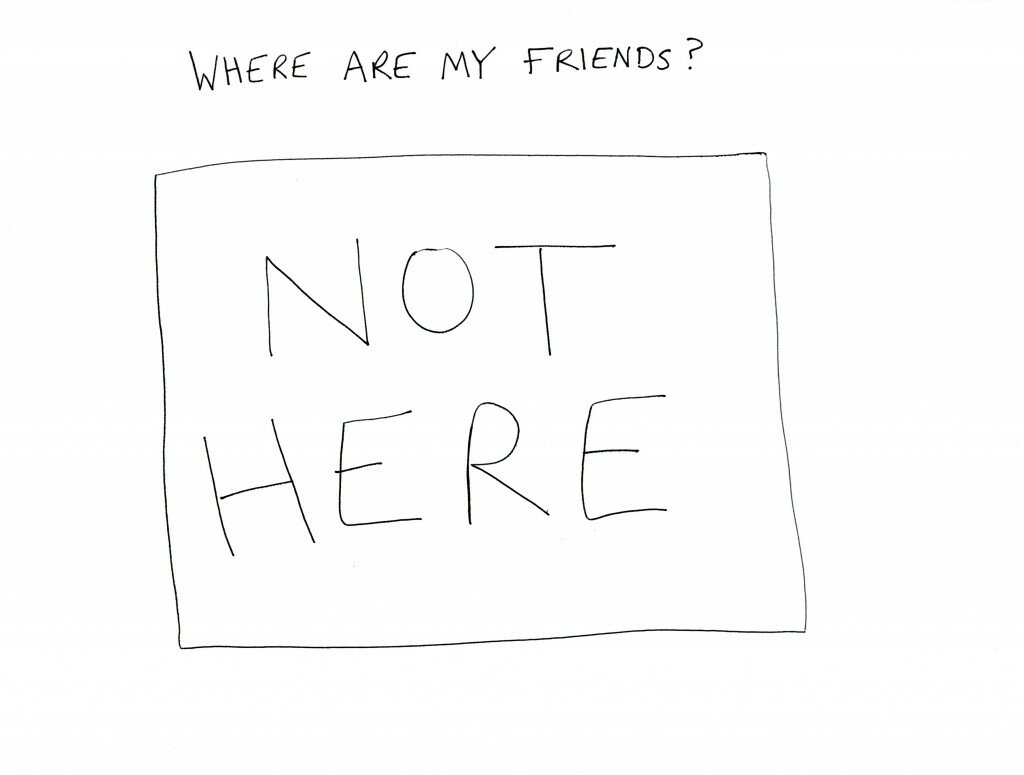

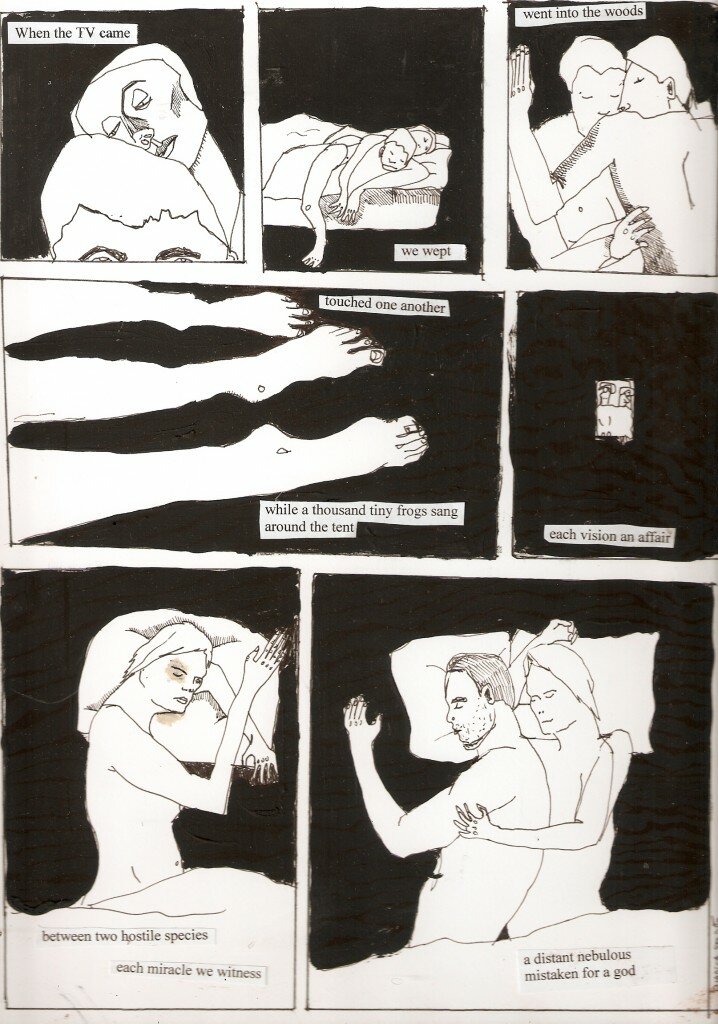

Storyboard approaches can be useful but they don’t reflect the potential for comics to communicate beyond sequential narrative boundaries. Scott McCloud, arguably the most influential comics scholar to date, tells us that possibilities for comics are seemingly endless, so too are attempts to define them (1993, 23). Yet by focusing on the notion of ‘closure’ and image interactions within closed grid structures, McCloud, like many comics critics, hasn’t encouraged comics concepts to expand very far past linear panel sequencing and narrative assumptions. Beyond McCloud’s definition of ‘images in deliberate sequence’ it’s possible to think of comics in terms of presenting simultaneous image-texts or web comics that feature hyperlinked content which takes readers in multiple directions rather than straight lines, or as a series of moments not bound by sequential panels and linear time constraints.

Interested in alternatives to linear, narrative analysis, (and wanting to talk to comics poets about their process), I started studying the ways poetry could be integrated in the creation and critique of comics. Speaking with several comics poetry creators, Matt Madden, Warren Craghead, Bianca Stone, Paul K. Tunis, Alexander Rothman, Derik Badman, Summer Browning, Michael Farrell, Eryon Franklin, Franklin Einspruch and Julie Delporte, it became apparent that the works they wanted to produce were those combining visual and verbal elements in ways that experimented with linear and narrative definitions of comics. Despite these attempts, and the growing field of alternative comics, the vocabulary of comics creation and criticism was largely limited to sequential definitions, narrative assumptions and linear modes of analysis. Comics critics like McCloud, Charles Hatfield, David Kunzle, David Beronä and Douglas Wolk, among others, view comics as narrative constructs, preferencing images in sequence over all other elements in the visual-verbal comics vocabulary. This narrative assumption is evidenced in Wolk’s review of Abstract Comics: The Anthology (ed. Molotiu, Andrei, 2009) in which he states, ‘anyone who’s used to reading more conventional sorts of comics is likely to reflexively impose narrative on these abstractions, to figure out just what each panel has to do with the next’. This statement is symptomatic of the narrative assumptions that limit aspects of comics criticism and creation.

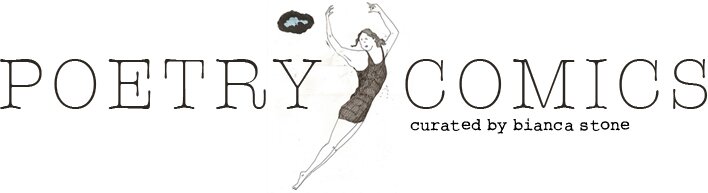

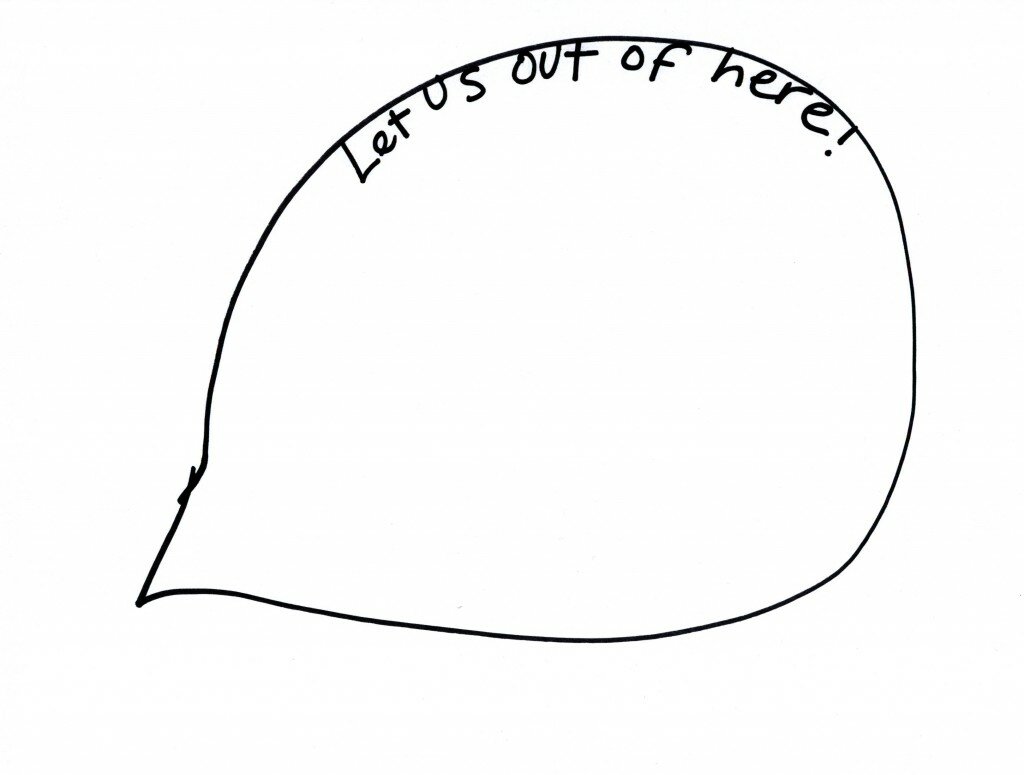

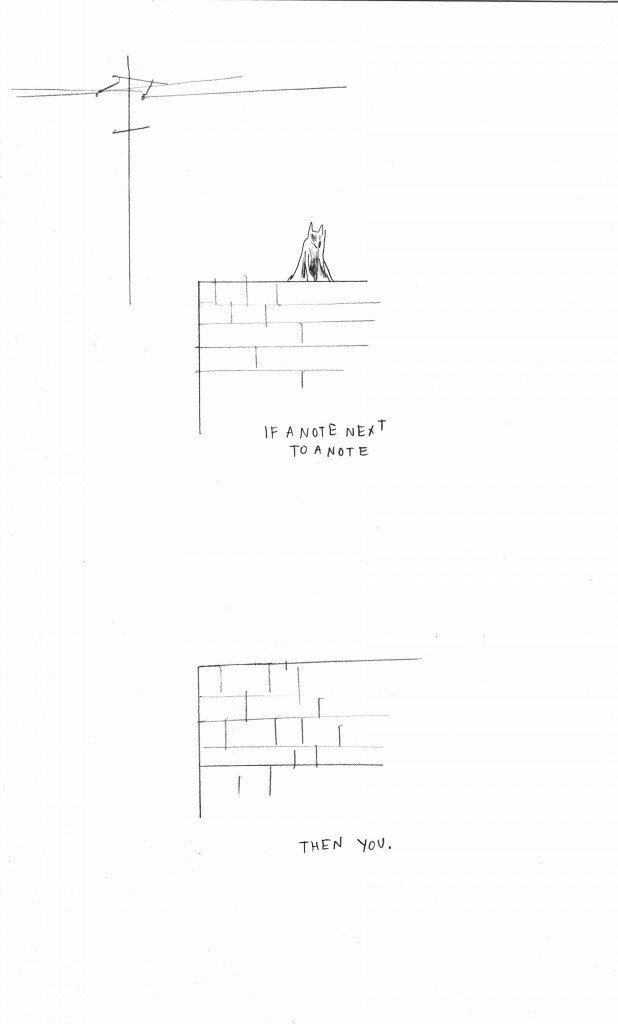

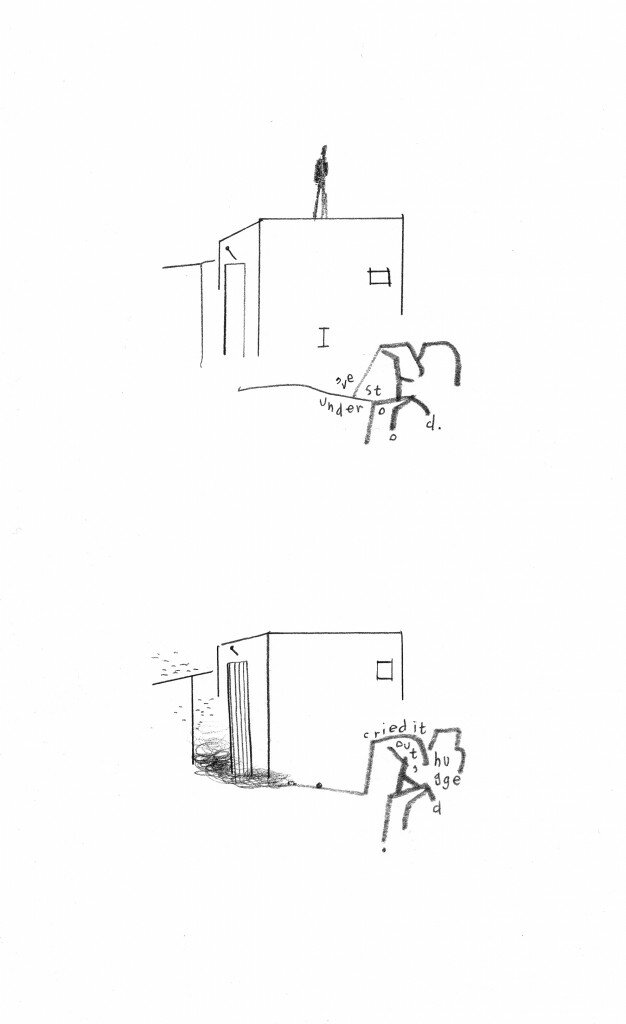

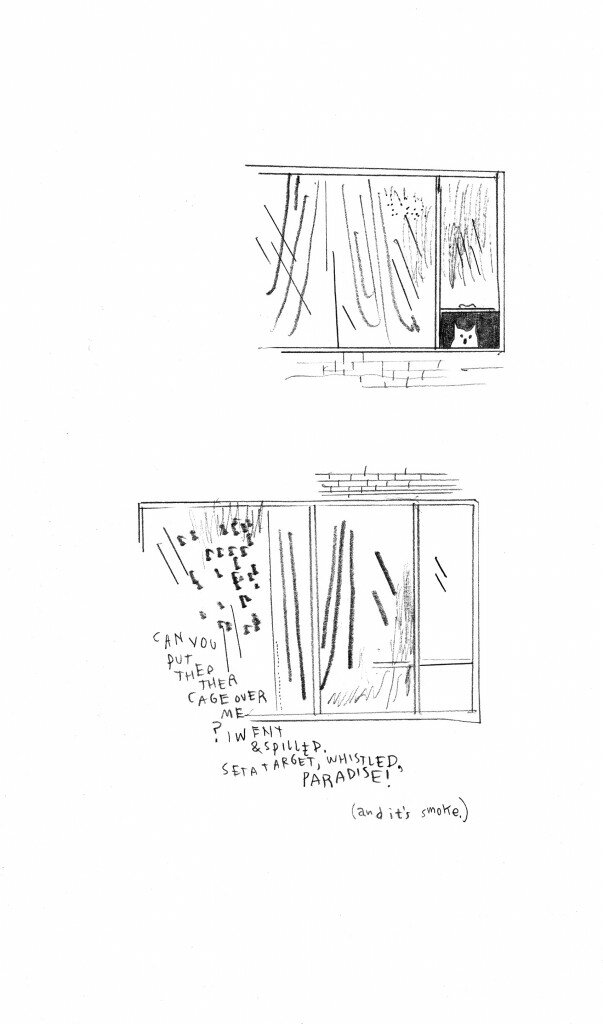

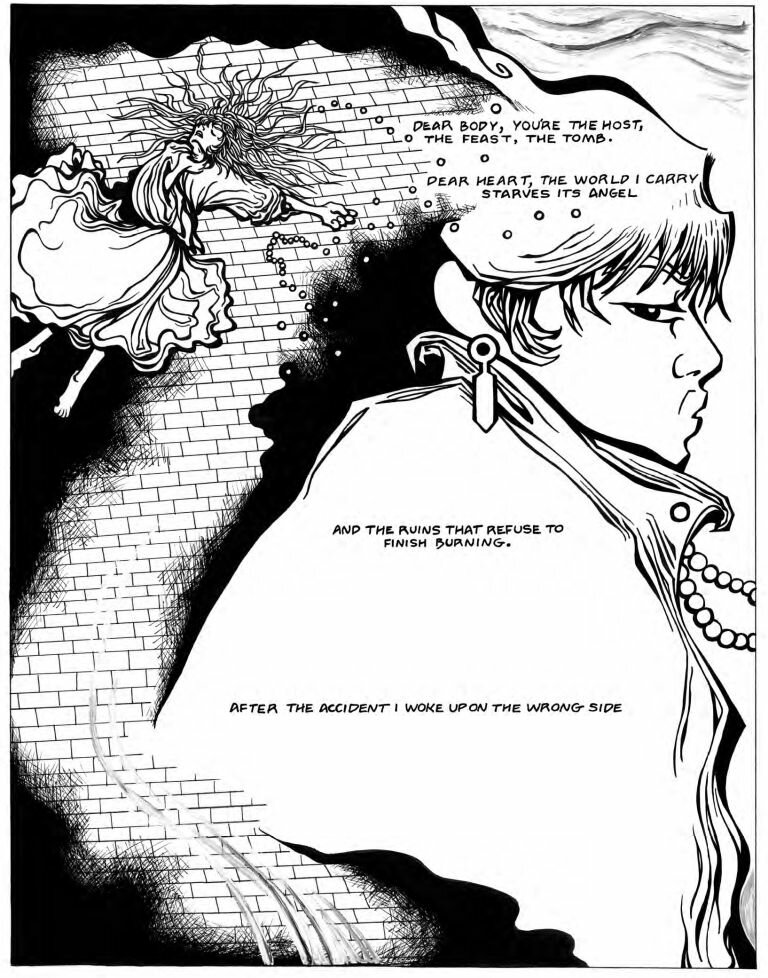

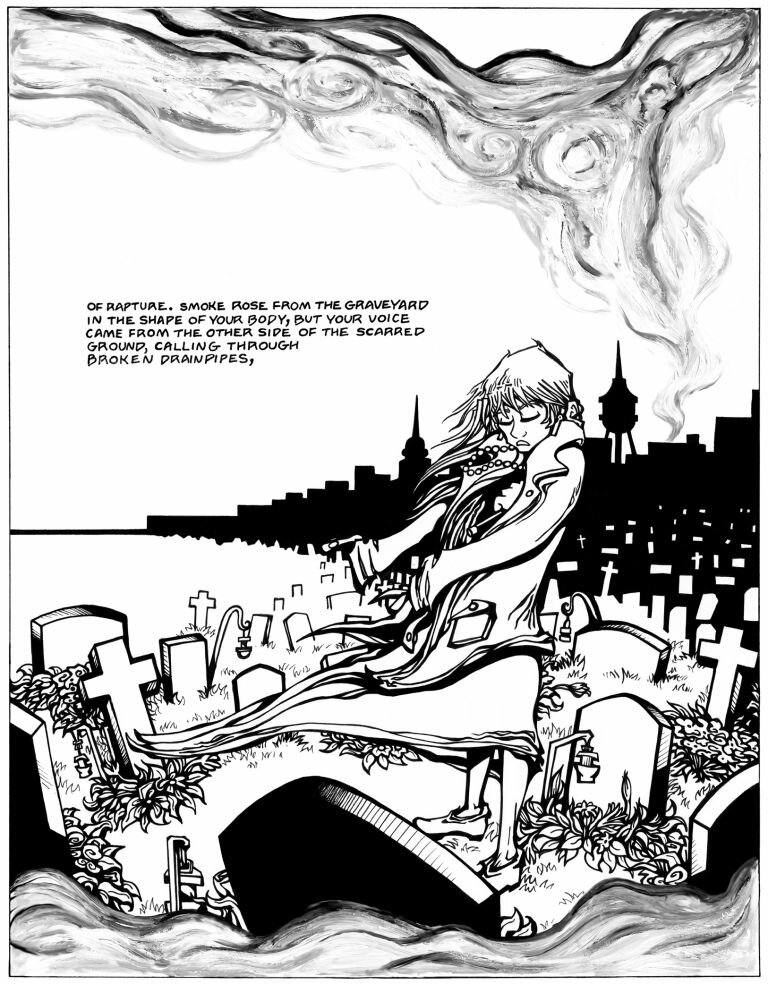

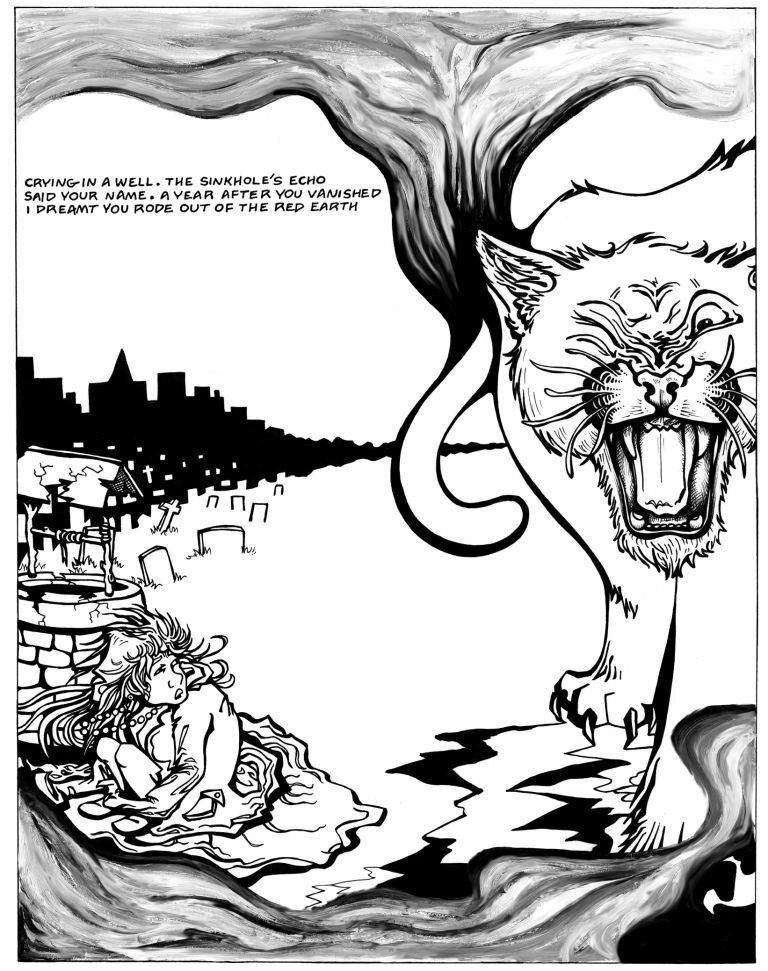

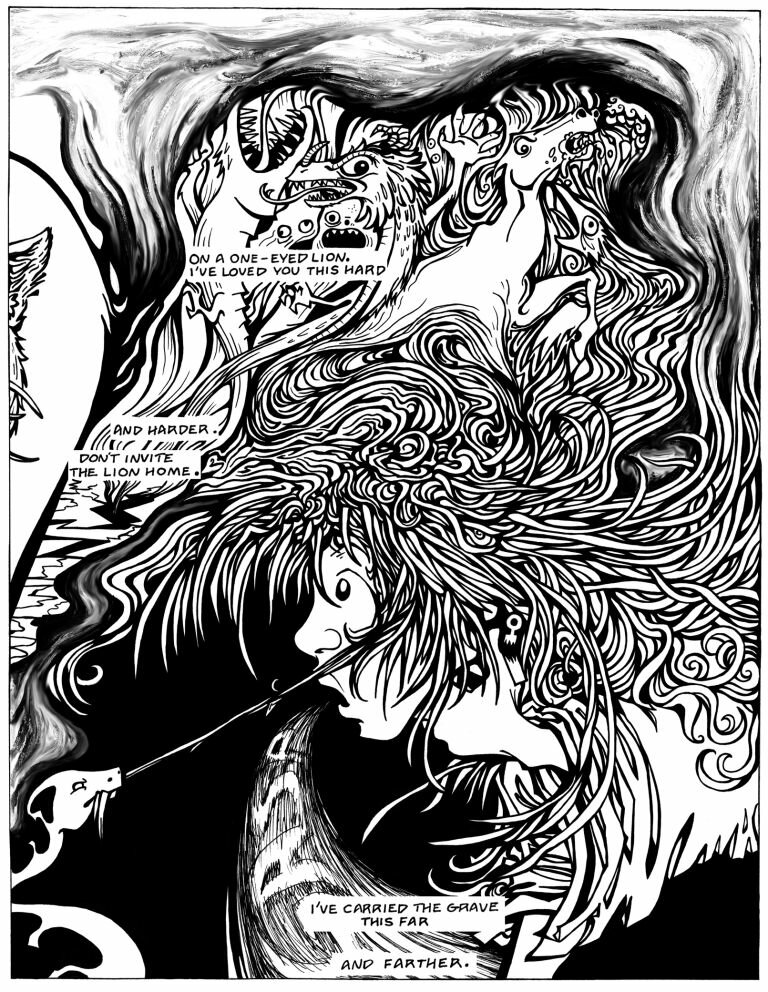

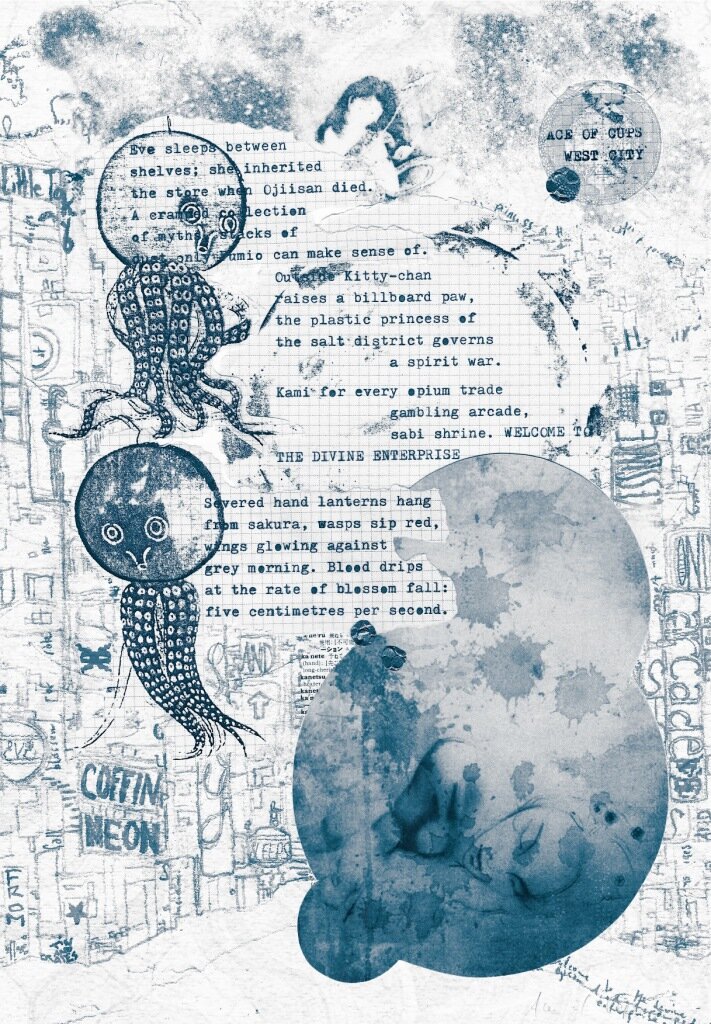

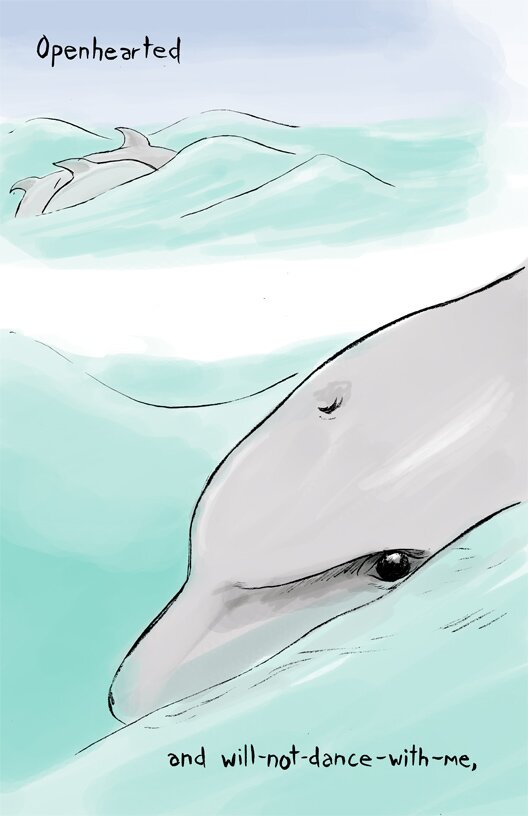

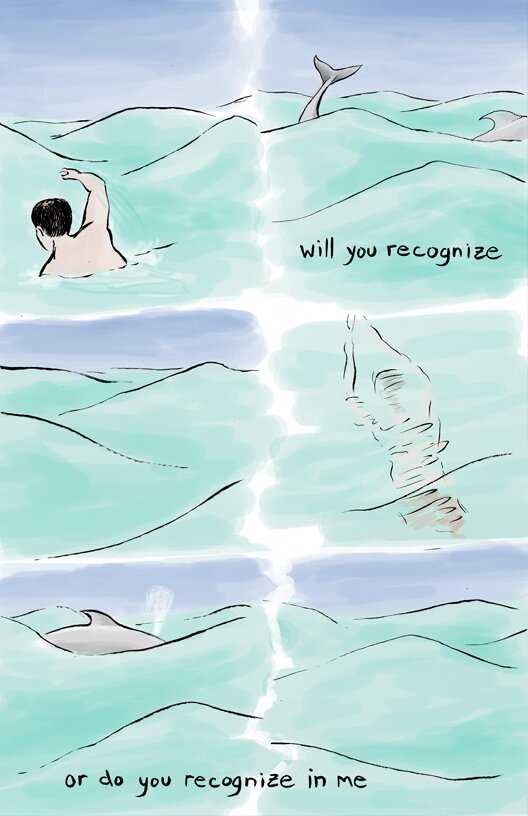

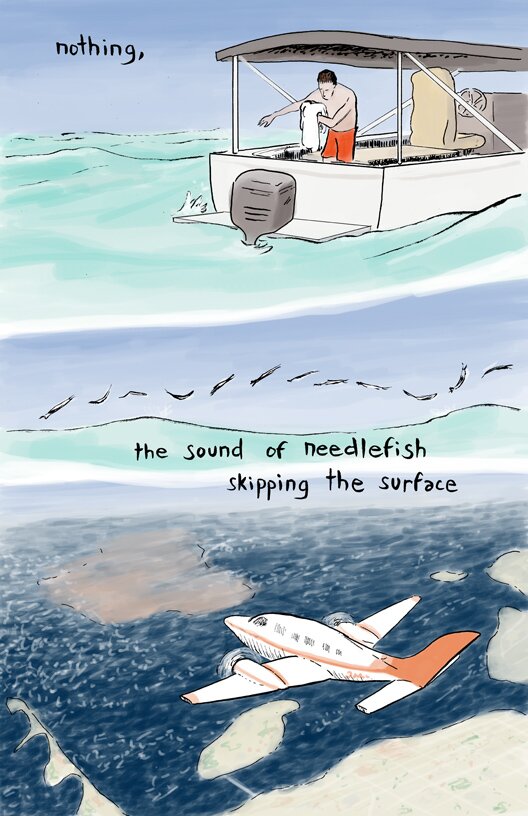

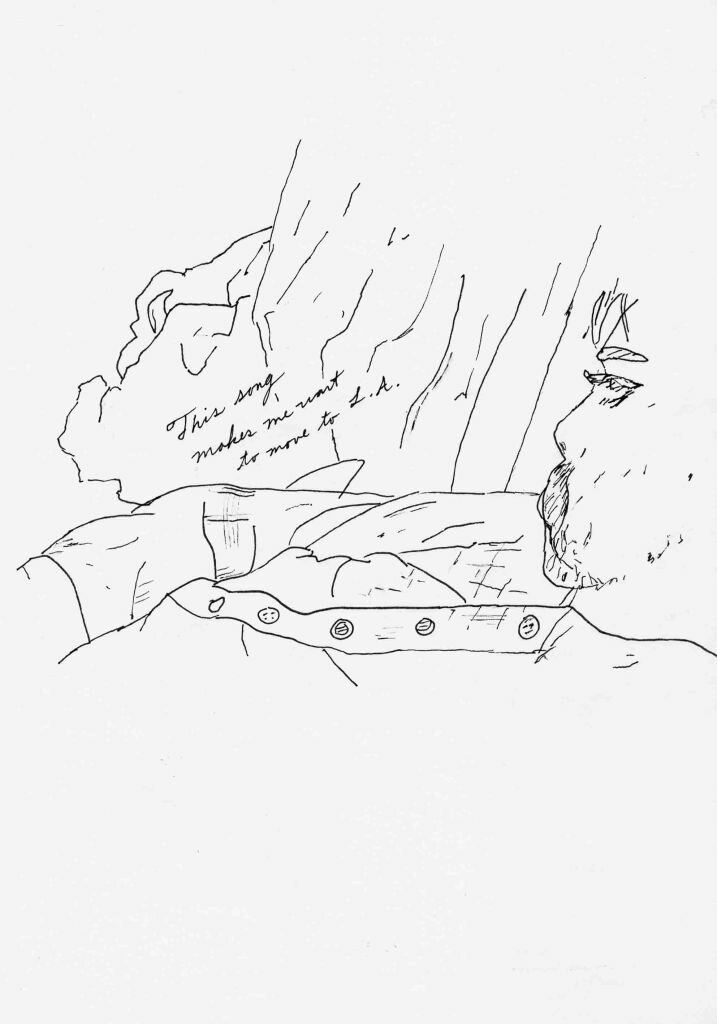

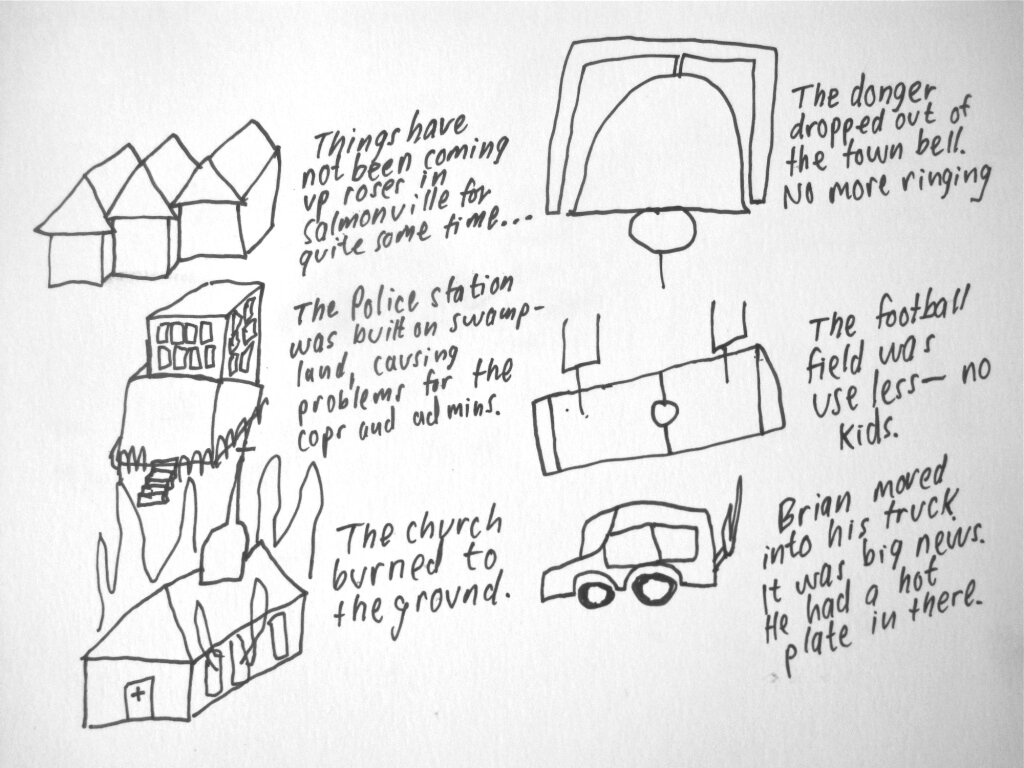

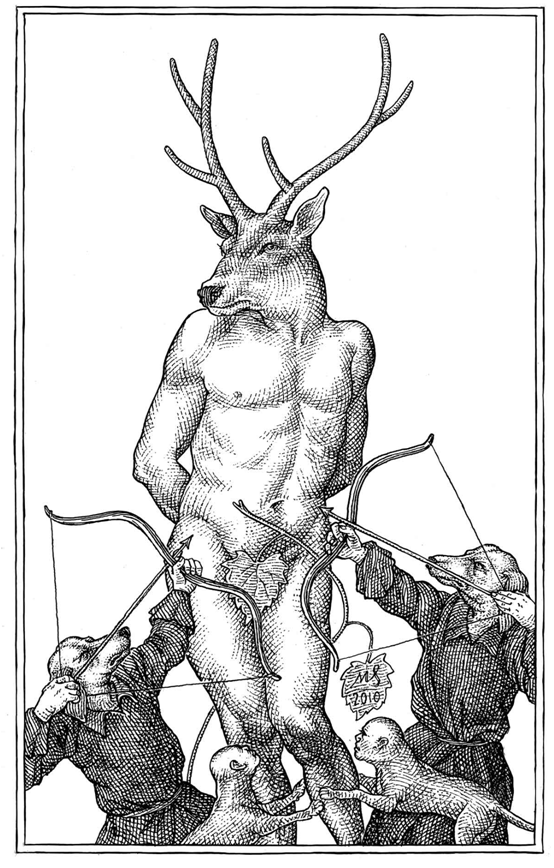

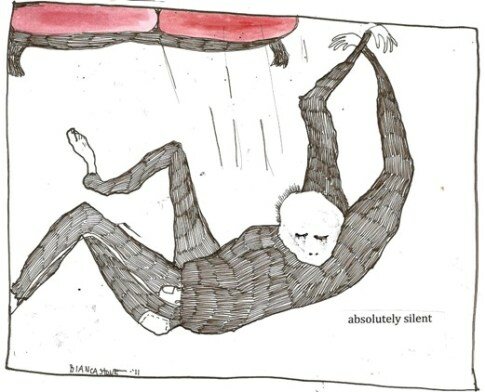

While narrative assumptions have formulated useful ways of creating and understanding comics in sequential linear order, they give little insight into non-linear, non-narrative works. There are gaps in existing narrative approaches when it comes to discussing the spatial arrangement and simultaneity of works like Warren Craghead’s HOW TO BE EVERYWHERE, Alan Moore’s PROMETHEA, Michael Farrell’s BREAK ME OUCH or many comics collected in Kramer’s Ergot editions or Andrei Molotiu’s Abstract Comics. Thinking sequentially can limit ways of interacting with comics like those by Kenneth Koch or Chris Ware in which text and image are presented simultaneously, or comics poetry by Alexander Rothman, Bianca Stone and Richard Hahn that linger in liminal spaces, or comics poems created entirely without panels. Instead, it is possible to understand how comics can be created and read in multiple directions, to enter the poetic experience instead of imposing narrative on it, to examine the liminal spaces and new associations between non-sequential components rather than skimming panels for linear associations.

The need for alternatives to narrative analysis is also noted by Jan Baetens in the article ‘Abstraction in Comics’ (2011) where he argues ‘[t]his a priori approach to narrative in comics as a mere instantiation of narrative in general is now under pressure’ (2011, 94). According to Baetens, the ‘phenomenon of abstraction in comics’ is cause for critical rethinking of narrative assumptions and more formal, medium specific approaches, especially in analysis of non-narrative comics (2011). Baetens suggests

[a]bstraction seems to be what resists narrativization, and conversely narrativization seems to be what dissolves abstraction. Abstract comics melt in the air when narrative walks in—and vice versa. That said, the imposition of narrative, as Wolk calls it, is far from being a simple or self-evident affair: much of the material gathered under the flag of abstract comics does resist in a very active way any attempt at immediate recognition and narrative translation (2011, 95-96).

Despite the narrative resistance of many comics, narrative ‘upgrades’ are continually imposed by sequential modes of analysis (Baetens, 2011, 106). Baetens contends, however, that ‘it is no less possible to gradually “downgrade” the narrative strength of apparently very narrative panels, pages, or sequences by becoming sensitive to the power of abstractive mechanisms’ (2011, 106). By re-focusing attention on individual segments, abstraction can be apprehended, narrative collapses, giving way to other modes of reading and seeing within the work.

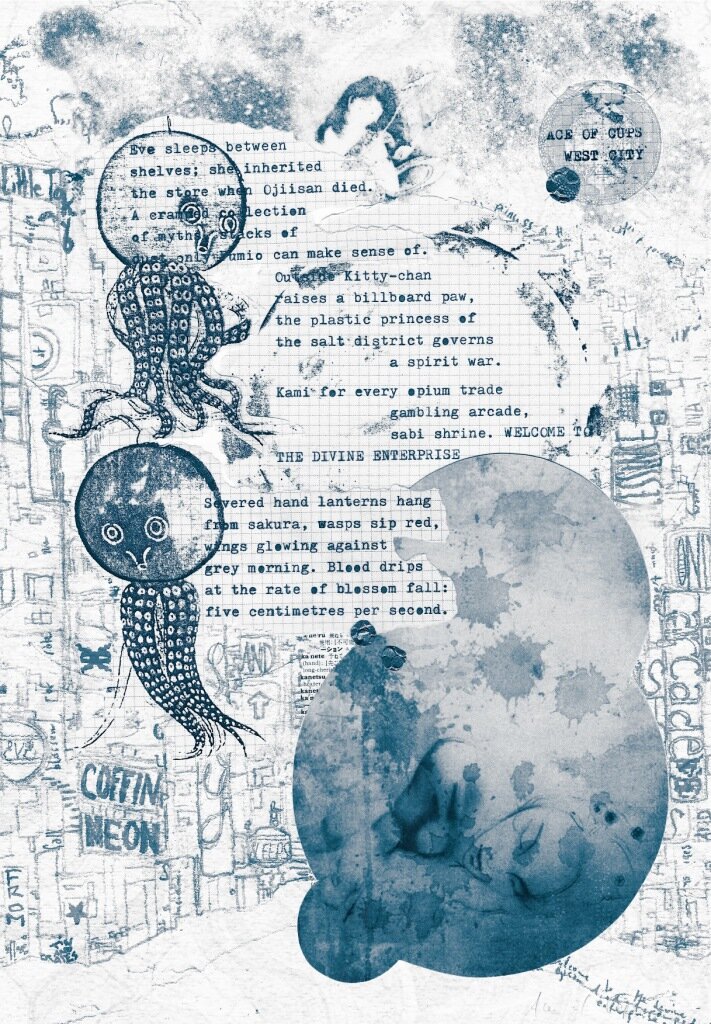

Besides Baetens, Brian McHale is another to illustrate that ‘the illusion that prose is a continuous medium, unsegmented, is a powerful one, with almost ideological force; nevertheless, it is demonstrably untrue’ (2009:23). Not only are there identifiable gaps between words, lines and pages, segmentation also occurs through seriality. This can be seen in comic series, where strips and episodes are released over months or years and characters passed from one creator to another. To address these gaps in narrative assumptions and the neglect of non-linear comics possibilities, ‘segmentivity’ presented a means to analysing both sequential and non-sequential comics. The concept of ‘segmentivity’ stems from Rachel Blau DuPlessis’ attempt to distinguish the components of poetry. According to DuPlessis, the underlying characteristic of poetry as a genre is its ‘ability to articulate and make meaning by selecting, deploying, and combining segments’(DuPlessis, 2006, 199). Segmentivity involves identifying and implementing ‘bounded units’ such as words, sentences, stanzas and spaces. Poetry, like all literary forms, is constructed of segments. Applied within comics, segmentivity can be used to examine the mechanics of panels, captions, speech balloons, gutters, typography, page layouts, countermeasure and the ways in which these elements can be used in both narrative and non-narrative, linear and non-linear contexts. Assessing where and how each visual or verbal segment is used can enable a richer understanding of spatial and syntactical experimentation.

Prior to captions and panels being placed in sequence, they are first ‘segmented’ as letters, words and images. These visual and verbal segments can then be accumulated and arranged in multiple ways. Not all of these components are inherently narrative, especially in the case of comics poetry and abstract comics. Accordingly, it can be argued that segmentation, not sequence, is the primary characteristic of comics. Sequence is a secondary element with narrative following behind. Narrative disclosure is dependent on the cognition and negotiation of gutters by the audience. This navigational process is what McCloud terms ‘closure’, where readers fill in gaps between panels, unifying visible and invisible moments to create ‘meaning’. Yet this process is not without issue as and contend. The practice of closure is also heavily reliant on panel structures and the narrative premise that gutters and spaces are to be leapt over, instead of explored as encouraged by many examples of comics poetry.

Traditionally, comics feature rectangular frames and nine-panel page grid structures with linear plot progressions. In poetry, meter and rhyme were once staple elements too, but modern techniques and technologies in both these forms have expanded possibilities through experimental spatial, syntactical and sound arrangements. Using segmentivity, creators and critics can understand that comics can present different perspectives of the same moment or image or idea, and that these moments can be equal to each other rather than sequential. Multi-linear and hyper-textual associations can also provide profitable alternatives that ‘overrun’ traditional image-text meanings. When one remains open to the ‘gaps’ and possibilities of both linear and non-linear readings in comics, as in poetry, profitable directions for navigating and creating new works appear.

Segmentivity moves towards an inclusive comics theory. This mosaic approach encompasses many modes of creation and criticism by focusing on the fundamental segments of visual and verbal language employed across all comics forms. Despite inclusive intentions, a question I’m often asked is whether such an approach is anti-narrative or anti-linear. In short, the answer is no. The process of identifying and applying segmentivity doesn’t dismiss narrative or linear forms, rather it enables visual and verbal components to be understood as pieces of a work that can contain both narrative and non-narrative elements depending on cognitive inclinations.

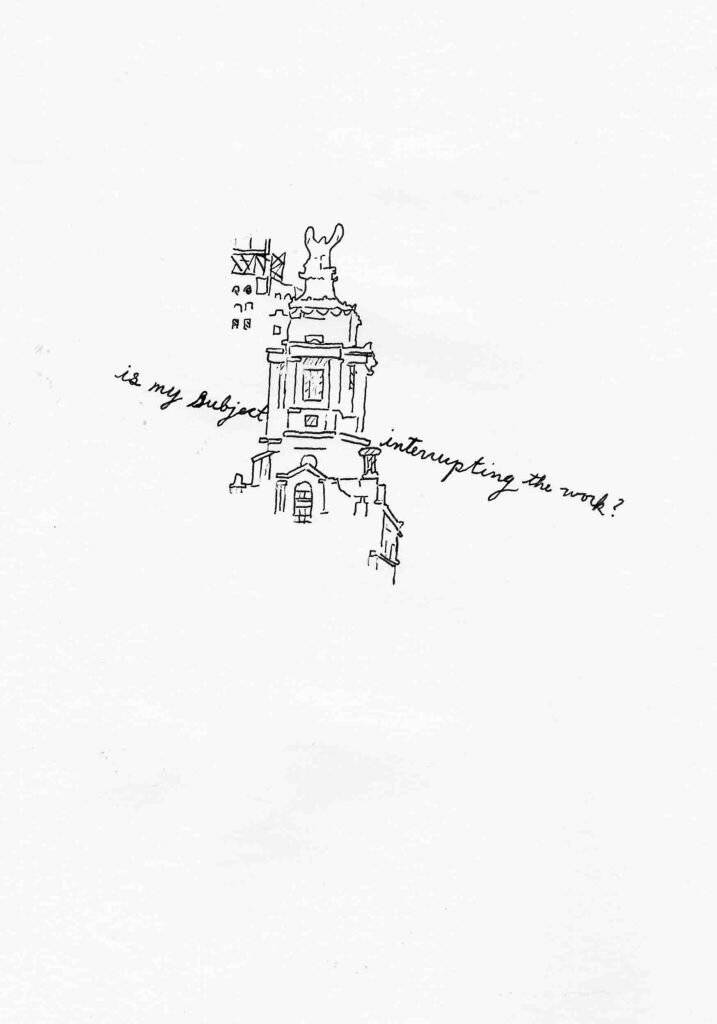

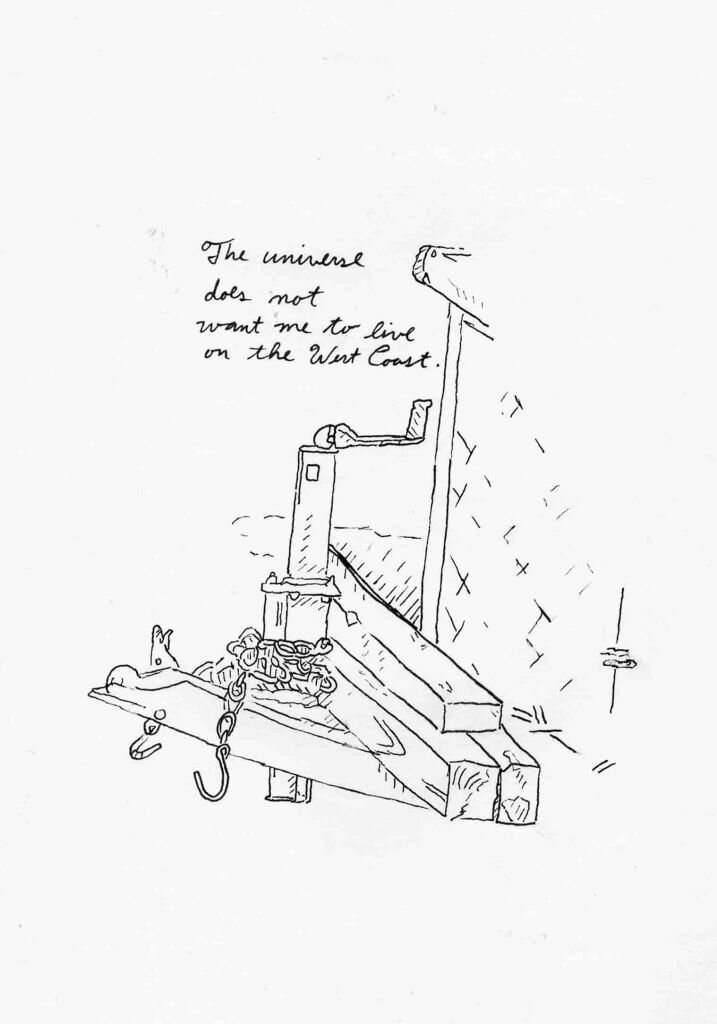

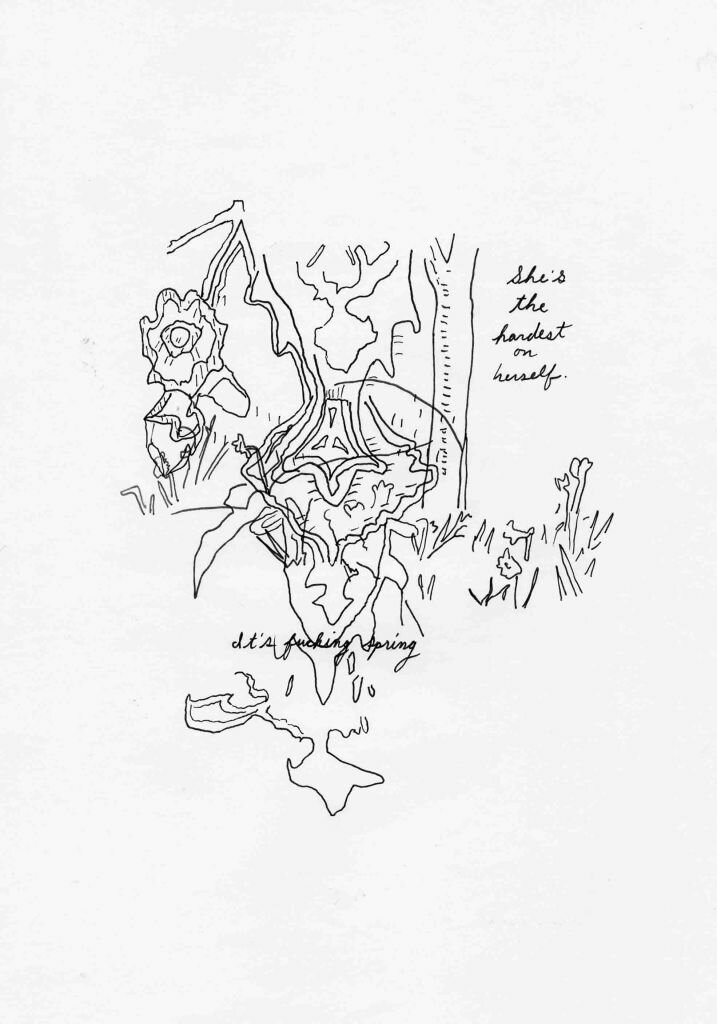

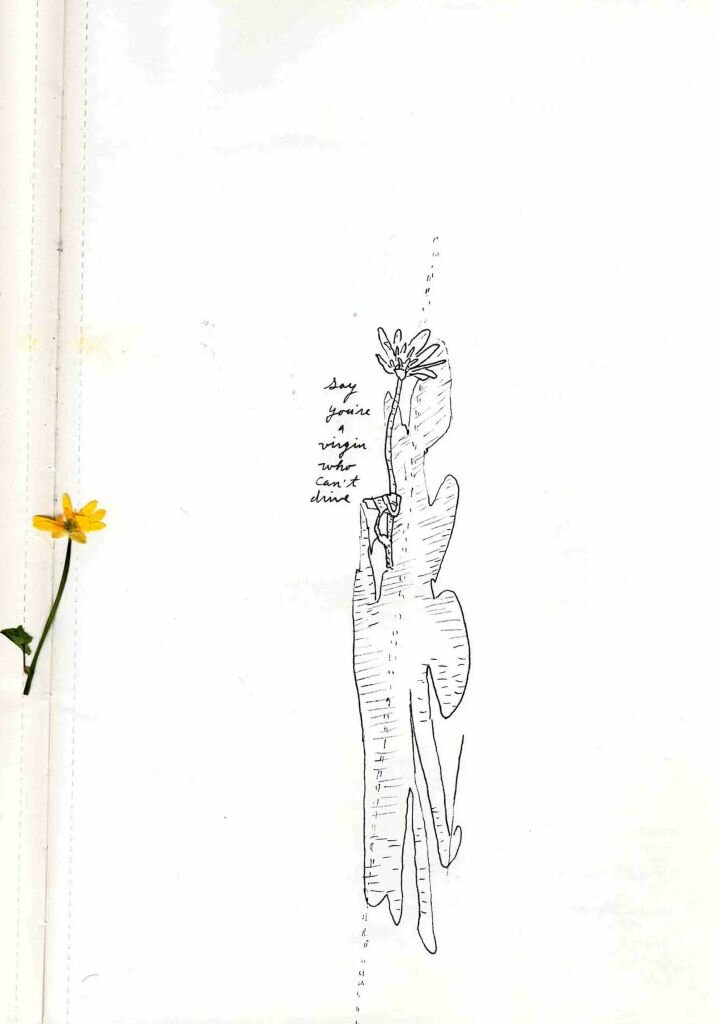

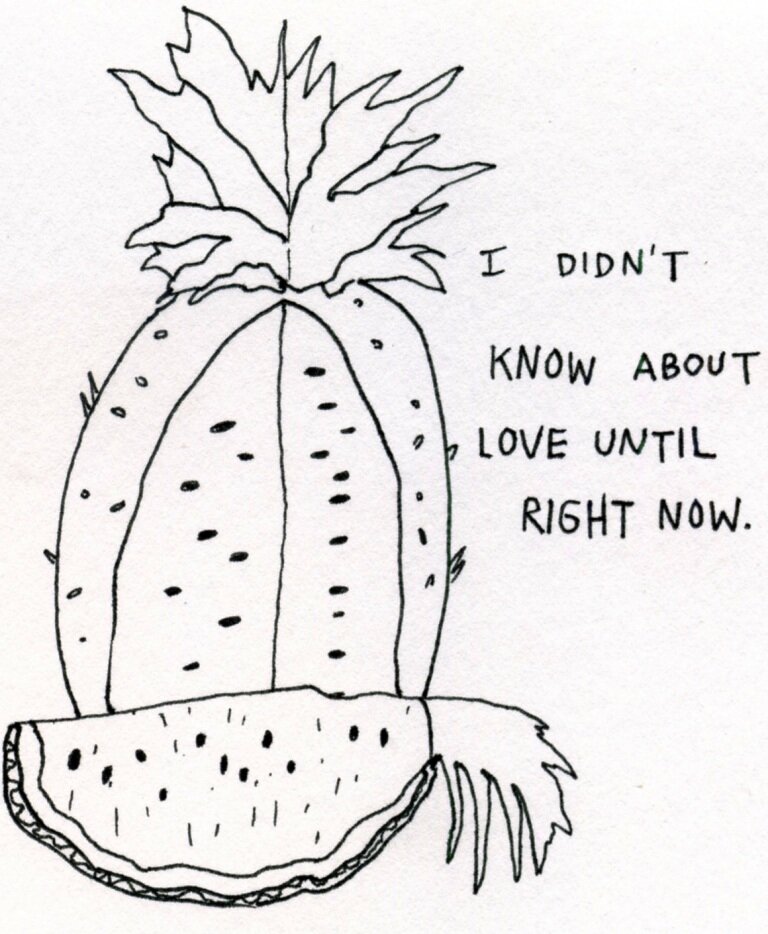

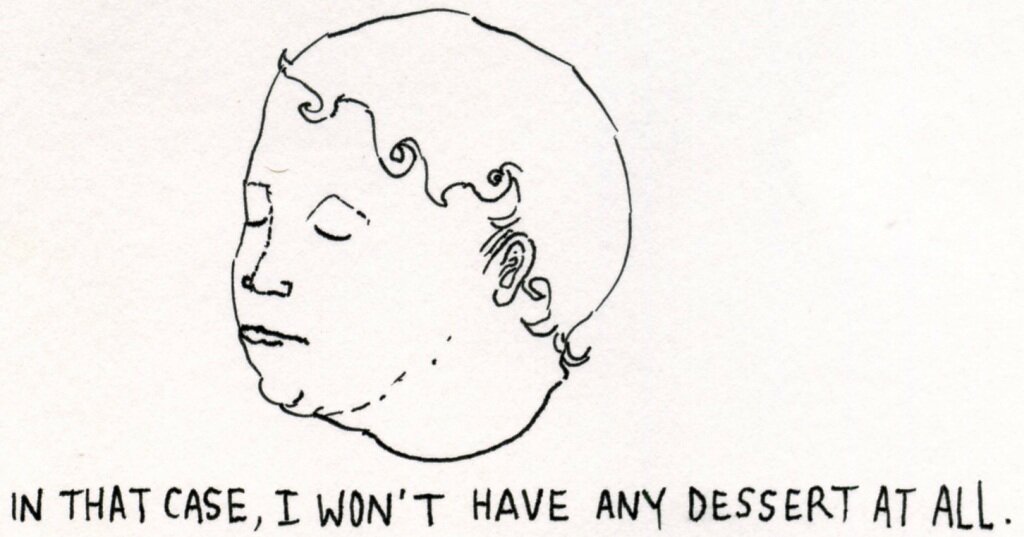

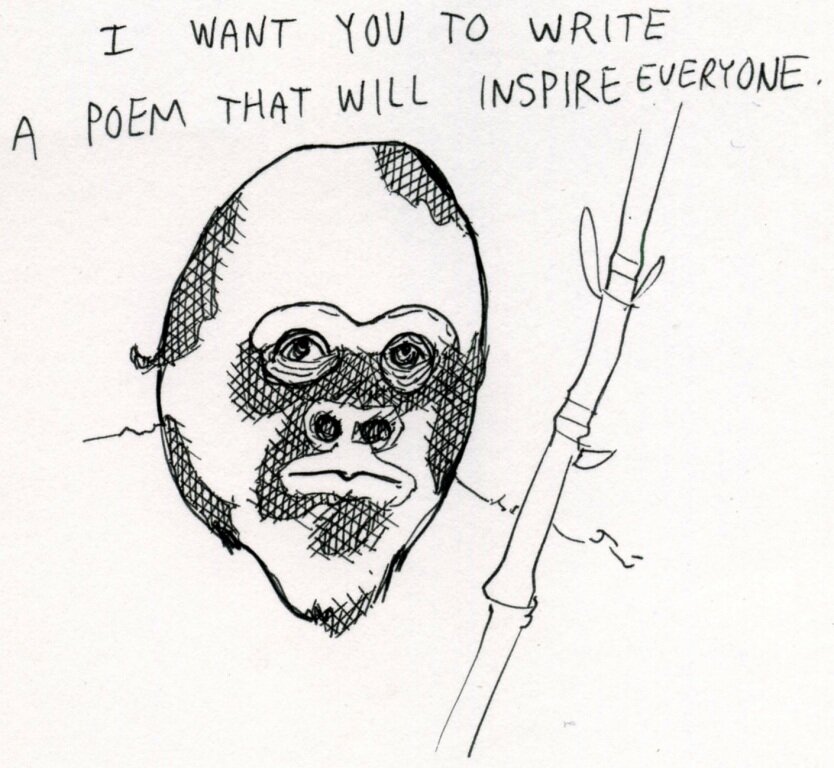

In testing the practical application of a theory of segmentivity I created the comics poetry series, ‘ANEKI’ in collaboration with five visual artists, Jackie Cavallaro, Skye O’Shea, Tamara Elkins, Anastasia McCloghry and Guillermo Batiz. The comics poems are symbolically and structurally based on the 78 cards of the tarot. These works can be read as narrative or non-narrative, in linear directions or in any formation of the cards. Through the lens of segmentivity, comics, like poems, have the potential to be understood in multiple directions. Combinations of visual and verbal segments are malleable and multi-linear. And although left to right reading and sequential ideology still dominate Western comics, there’s no absolute authority that forces readers to follow a set path, as Fawkes’ comic, One Soul, superbly demonstrates. This is one of many works to illustrate the phenomenon of non-linear, abstract and comics poetry that employ simultaneity over set sequence (Baetens, 2011). Examples of this poetic turn can also be found in comics by Koch, Craghead, Ware, Hankiewicz, Jas H. Duke and Rothman who experiment with rhymed images or freeing images from panels all together, circular page constructions and loops of text that reveal a myriad of reading possibility for comics. Overturning predictable sequencing of traditional comics, these works demonstrate the profitable potential of poetic ‘gaps’, silences and deliberate syntactical disjunction to incite meaning. In realising the potential of comics and comics poetry, segmentivity encourages creators and critics to become aware of the myriad of ways in which it is possible to write poetry in the language of comics, and for comics to employ the spectrum of poetic devices from caesura to rhymed couplets.

This is by is by no means an exhaustive account of comics criticism or comics poetry, rather a survey of selected perspectives that exposes some of the gaps and possibilities presented to date. A more comprehensive analysis of criticism and concentrated studies of comics poetry can be found in my research ‘Comics Poetry: Beyond Sequential Boundaries’.

___________________________________________________________

Tamryn Bennett is an Australian writer and visual artist living in Mexico. Since 2004 she has exhibited artists books, illustrations and comics poetry in Sydney, Melbourne and Mexico. Her projects are created in collaboration with artists, designers, photographers and musicians. Tamryn’s poetry and essays have appeared in Five Bells, Nth Degree, Mascara Literary Review and various academic publications. She has a PhD in Comics Poetry from The University of New South Wales and when in Sydney was Art & Publications Director for .

Selected references

Baetens, Jan. (2011). Abstraction in Comics. Substance # 124, Vol.40, no.1, pp. 94-113.

DuPlessis, Blau Rachel. (2006). Blue studios: Poetry and its cultural work. United States: University of Alabama Press.

Hatfield, Charles. (2005). Alternative Comics: An Emerging Literature. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Horrocks, Dylan. (2001). Inventing Comics: Scott McCloud’s Definition of Comics. The Comics Journal #234, (www.hicksville.co.nz/Inventing%20Comics.htm).

McCloud, Scott. (1993). Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: Harper Perennial.

McHale, Brian. (2009). Beginning to Think about Narrative in Poetry. Narrative. Vol. 17, No. 1, pp.11-27.

Molotui, Andrei, Ed. (2009). Abstract Comics: The Anthology: 1967-2009. Seattle: Fantagraphics Books.

Wolk, Douglas. (2007). Reading Comics: How Graphic Novels Work and What They Mean. Cambridge: Da Capo Press.