In many of the pieces I’ve turned in for a Creative Writing class, they’ve been returned with red ink underlining the first line, usually with comments like “This needs to have more impact” or “How does this draw in the reader?” Plus, there’s always one class period dedicated entirely to the crafting of the first line. Even now, as I’m writing this, I’m wondering if these first sentences are really the best ways to open this article.

The first lines of our poems can promise us interested audience or convince them our work is worth skipping over. From what I’ve learned from my studies so far, a good opening grabs a reader’s attention. I’ve also seen from my own reading that trying too hard to get their notice can make the lines feel forced and serve as a worse opening than something more generic.

This emphasis in my classes and the complexity of first lines I’ve experienced in my own writing led me to wonder what truly makes a great first line and what people’s favorite first lines are. I took to THEthe’s and page to ask our followers.

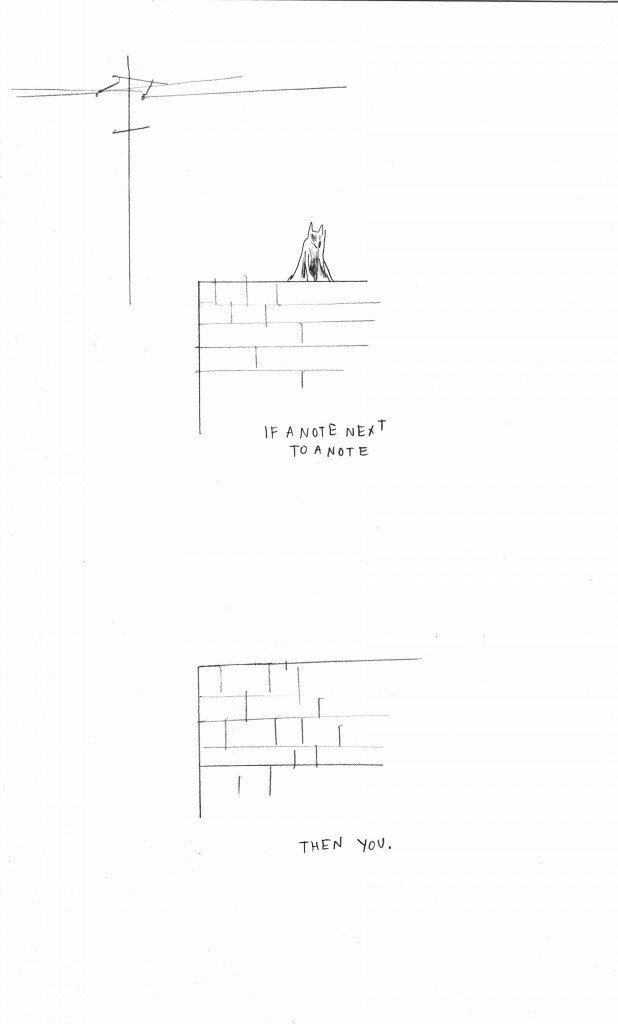

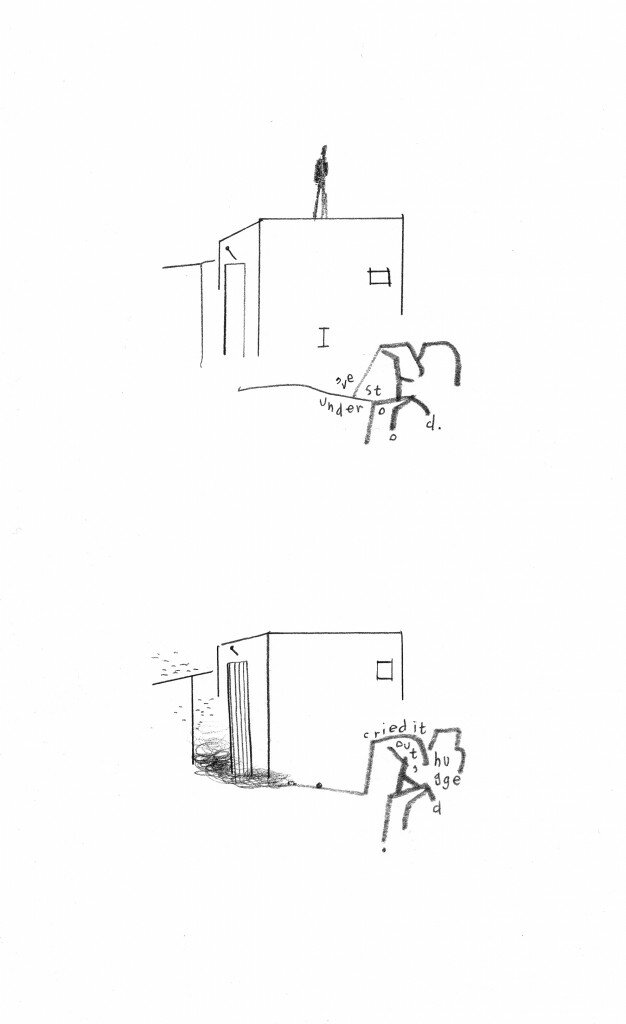

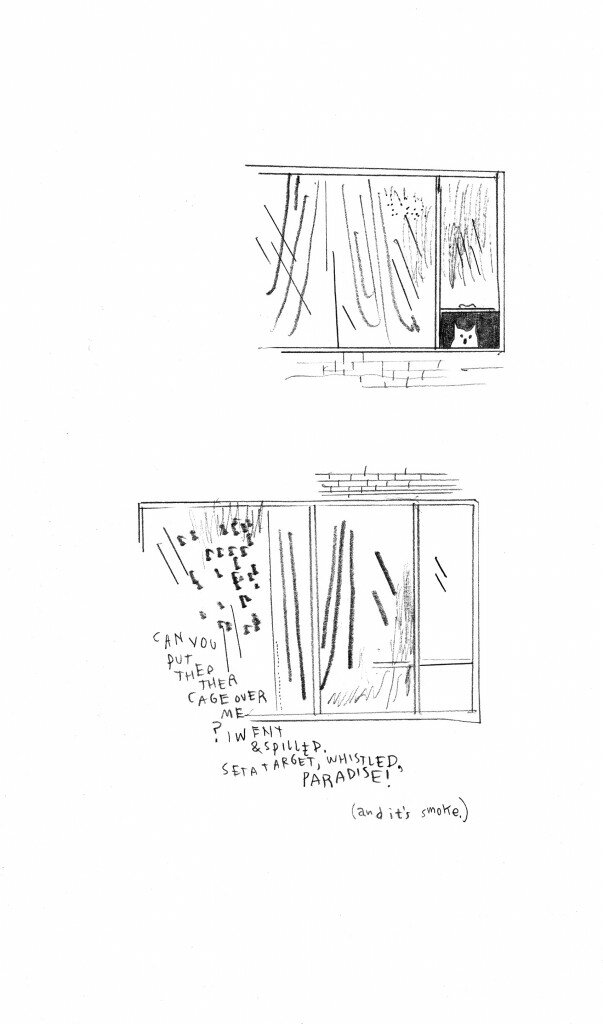

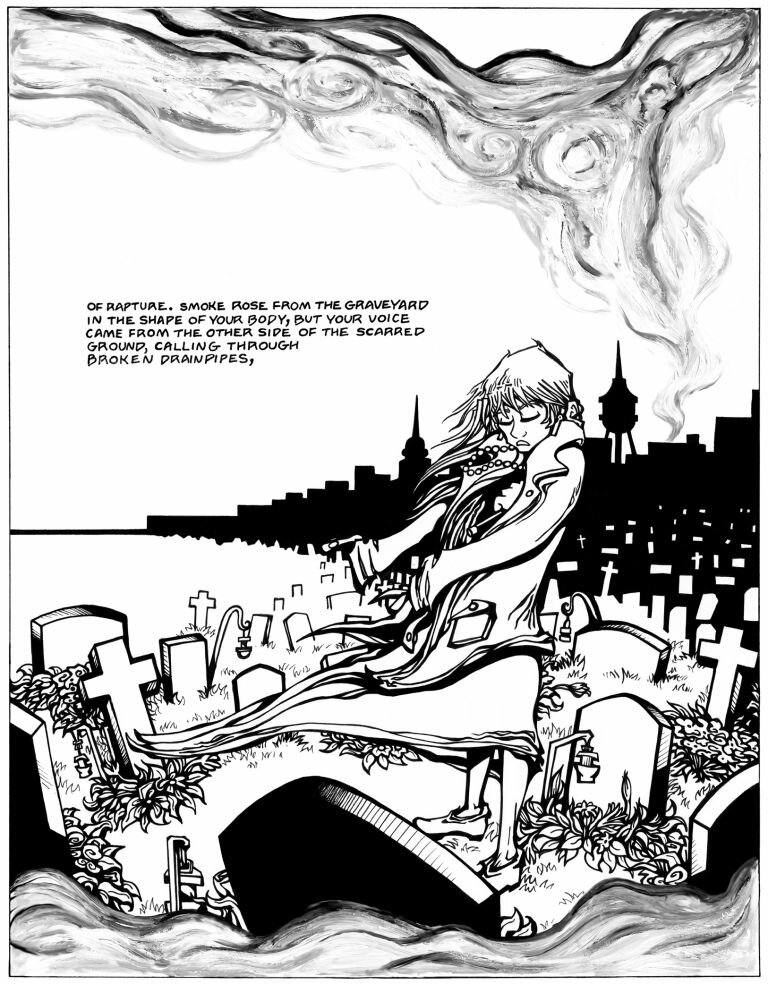

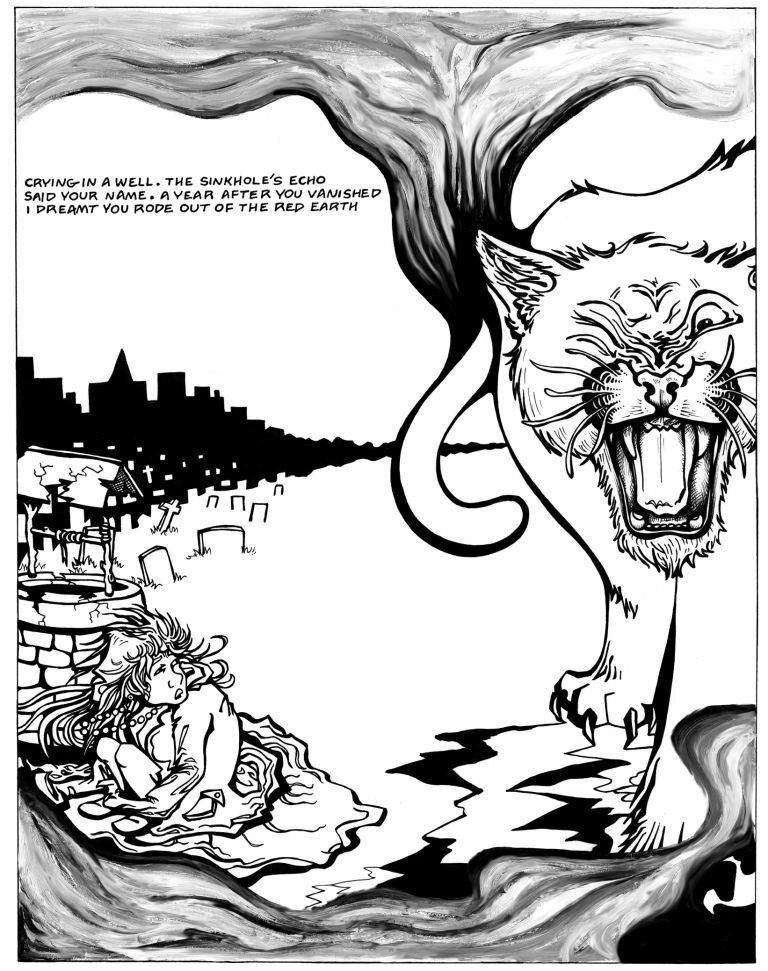

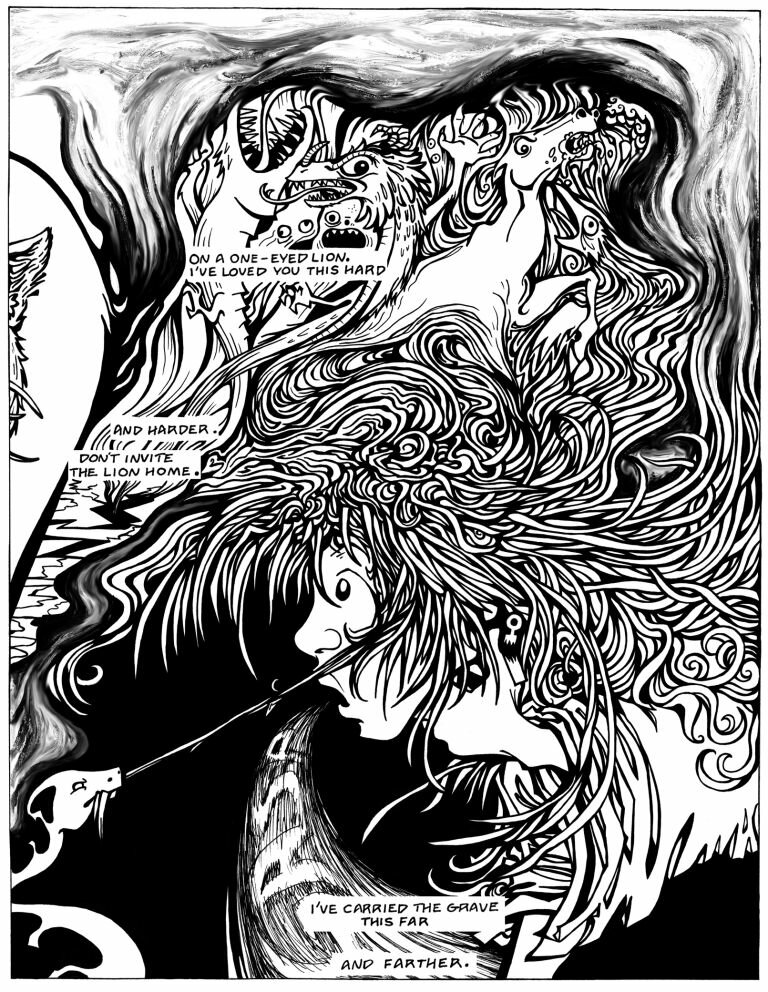

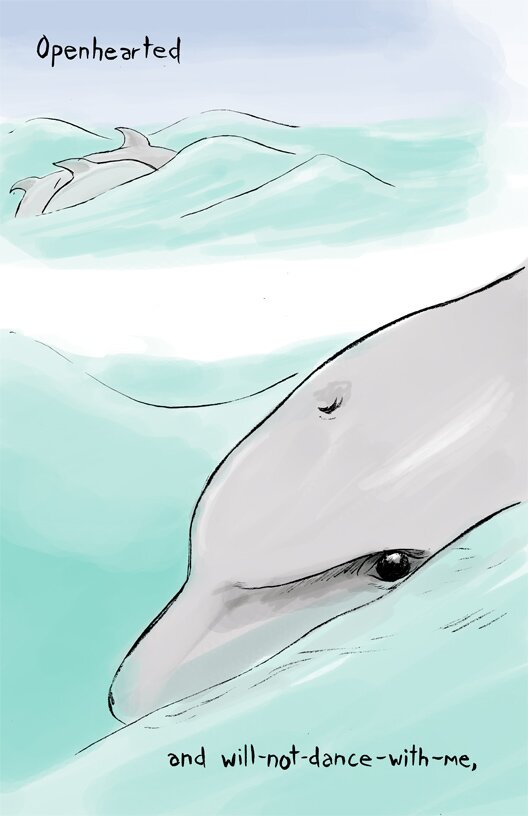

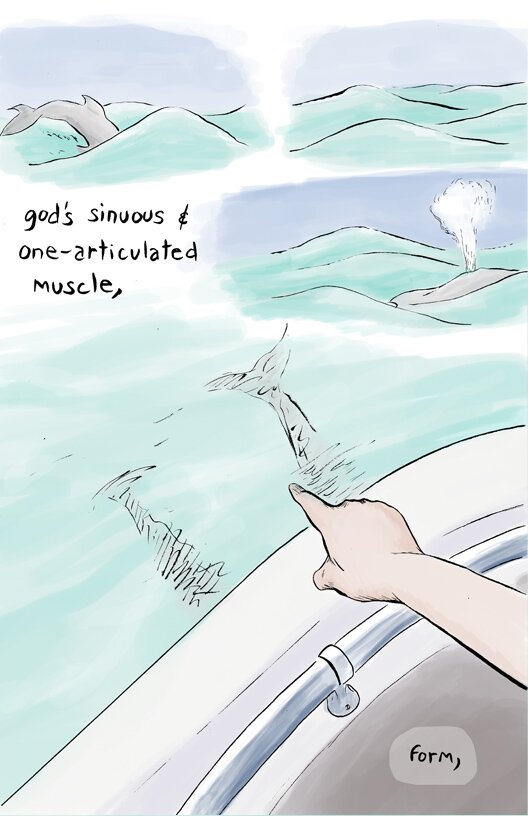

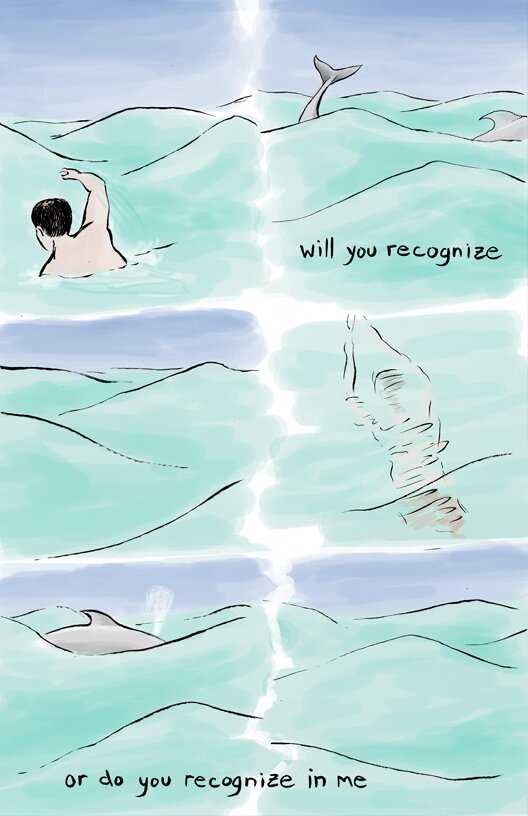

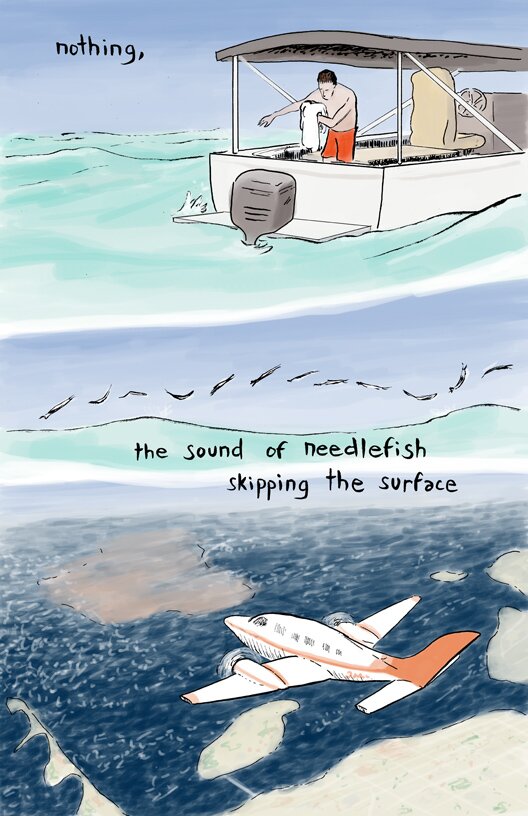

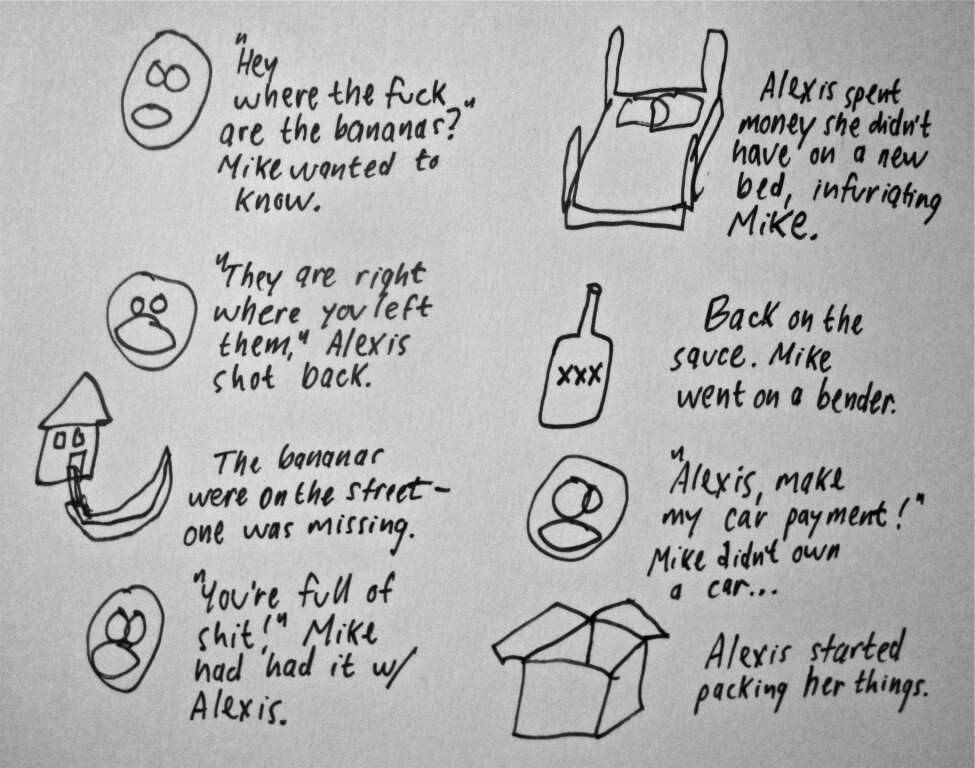

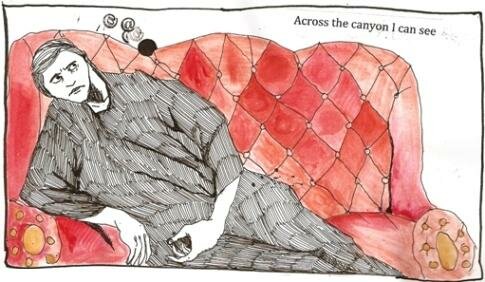

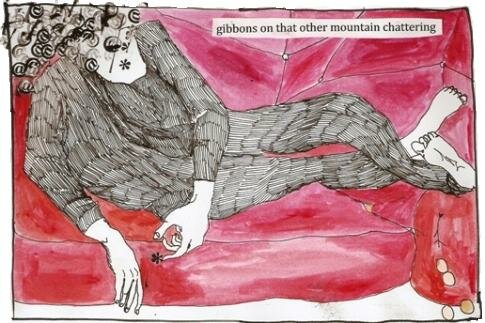

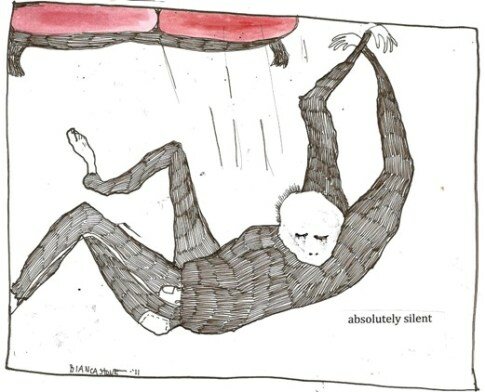

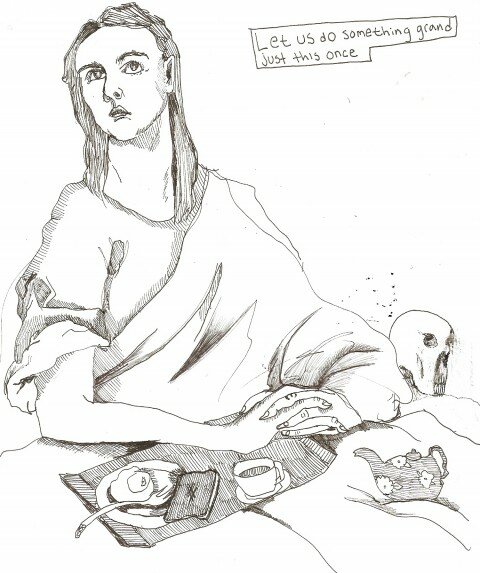

Some of our responses were from our reader’s own poems:

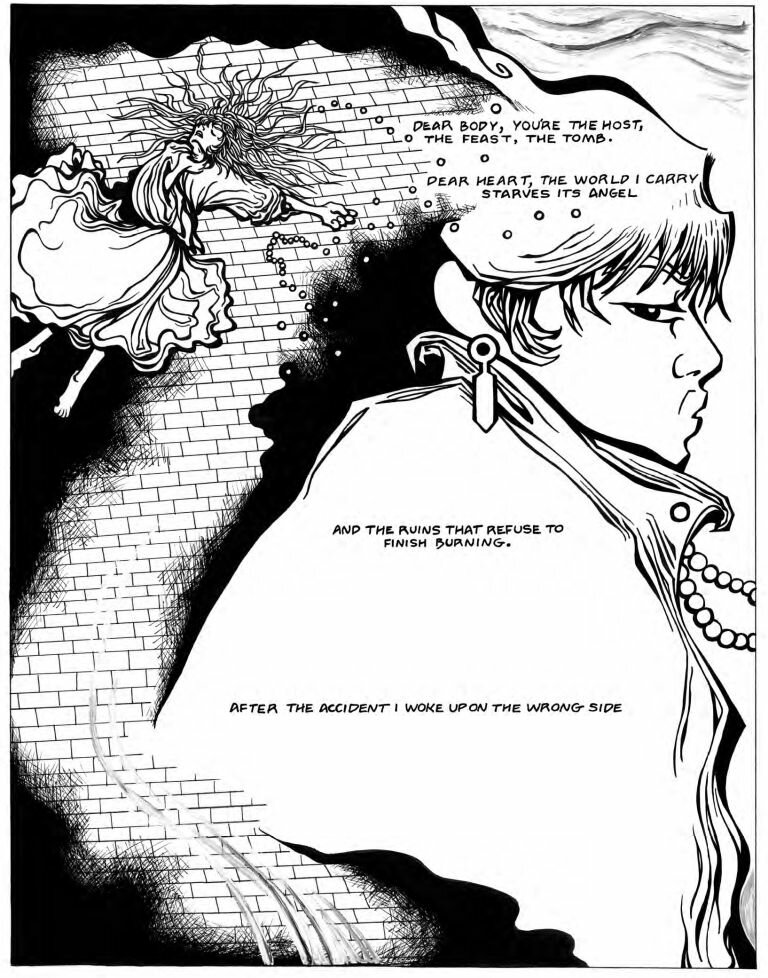

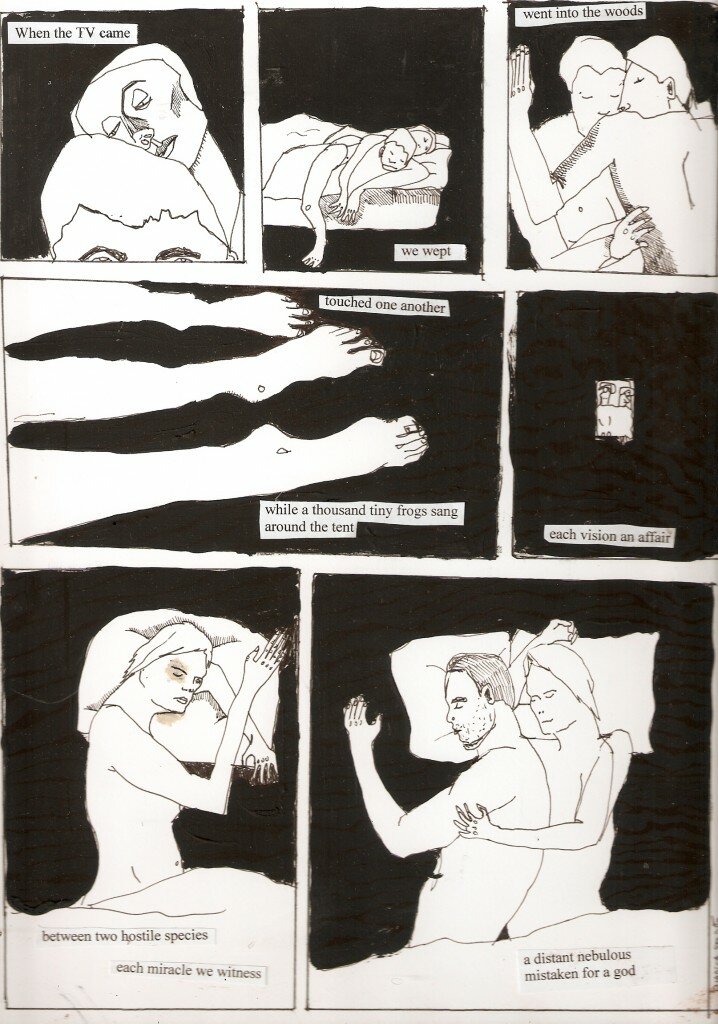

Others responded with some published and famous works:

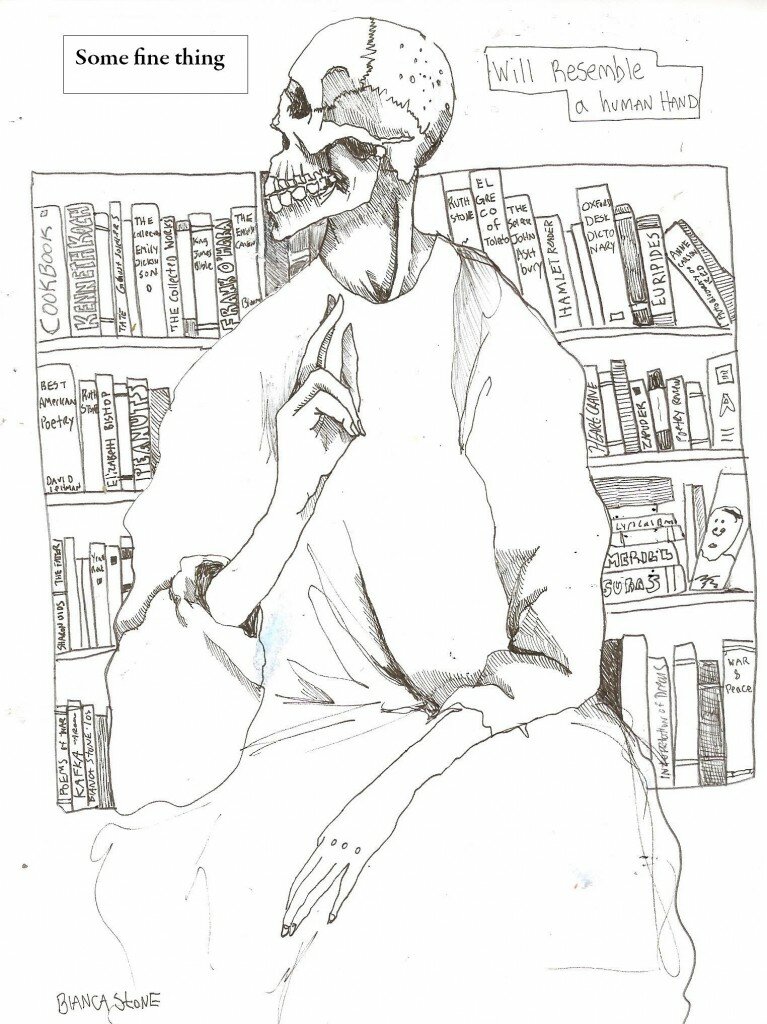

While I had read some of these poems before this gave me the opportunity to look up many of these poems. What I noticed was that many of these first lines left a strong visual image along with an emotional connection, most notably love or sadness. An image by itself in an opening can be memorable, as in one of our followers’ original poem, which compares cervical mucus to egg whites. This also gives a bit a mystery to beginning of the piece because although the bodily fluid obviously will relate somehow, the reader must read more to find out what’s going on in in the piece. It can sometimes be difficult to pull out extraordinary descriptions but simpler image may be more readily available. In this case, it may be more effective to juxtapose the image with a strong emotion that isn’t usually associated with that image. For example, one follower mentioned the opening to Louise Gluck’s “The Wild Iris.” While the image of a door is not all that exciting, and certainly not very memorable, when combined with the feeling of suffering the lines become a powerful combination that pulls the reader in. Sorrow isn’t typically a feeling one would think of alongside something as typical as a door, and by putting them together the poet creates interest.

Still there are other amazing poetic openings not mentioned by our followers, but still are worth examining. For instance, Homer’s epic, The Odyssey, begins with “Tell me, O muse, of that ingenious hero who travelled far and wide after he had sacked the famous town of Troy.” While this line doesn’t meet either of the characteristics previously mentioned, it does give the reader (or in the case was for Homer’s audience: the listener) an immediate sense of what the following story is about. We learn that our main character is smart, strong, and a veteran of the famous battle of Troy. We also know that this story will be about his journey after the battle, and that it will be a long journey. Also, Milton’s Paradise Lost opens by telling the readers what they are about to experience. The first book opens with “Of Mans First Disobedience, and the Fruit/Of that Forbidden Tree, whose mortal taste/ Brought Death into the World, and all our woe.” It is becomes obvious to the reader within these first few lines that the tale will be about Adam and Eve and their infamous story of the origin of sin. Neither of these poems open with bold imagery or obvious emotional connections, but they are still regarded as iconic and beautiful first lines. There is something in the simplicity of these lines, along with those of other epic poems, which are inviting to a reader. These lines seduce the reader with the promise of an adventure or tale, which the reader then gets to experience vicariously through the poet and the characters in the poem. There is also this hint of a narrative in the lyrical first lines. It may not be as direct as epic poems, but it is there in an unusual image, or evocative phrase. Look again at the Louise Gluck’s line. Both the suffering and the door promise a story of some sort, one of an upsetting past and the other of a hopeful future. However, there is a lack of immediacy in epic poems that is present in lyrical poetry.

This easily explained by the difference in lengths between these exceptionally longer epic poems and the shorter lyrical pieces. Epic poetry has many chapters, in some cases books, in which to ease the reader into a scene and topic of a story. Meanwhile, lyrical poems have less space available and must get to the essential parts of the scene immediately. Shorter works from the same time periods as Homer and Milton have similar first lines to modern lyrical poetry.

There is also a sense of intimacy in the openings of lyrical poetry that is lacking in the epic poems. Homer’s work addresses the muses in the first line, seemingly talking to a third party. The epic poem begins with holding the reader at a distance, although it invites them to read the story. Lyrical poetry is more personal and usually addresses a “you” or “we”, even in the first lines of the poems. These lines give the allusion that the poet is speaking directly to the reader. Whoever the poem is about served as a sort of “muse” to the poet and that’s who they are truly addressing, but the language gives the sense that it can be about anyone, including the reader.

Thanks to all of our followers who responded!