The Eggshell Parade brings you a reading and interview from poet Kelli Russell Agodon.

The Eggshell Parade brings you a reading and interview from poet Kelli Russell Agodon.

Ornithology Lesson

First thing we should do/if we see each other again is to make/a cage of our bodies

—Nick Flynn, forgetting something

1.

You find me pirouetting slow

in a tent before an exaltation of men,

dim lights, the scent of refuse

and popcorn and tobacco spit,

the clink of coins changing hands,

the lure of something both sordid

and sanctified.

2.

You follow me everywhere.

Where do you sleep?

I show you my thatch of straw.

What do you eat?

I serve you cave crickets and potato bugs.

How do you bathe?

We stand outside for an entire rain

leaping into puddles.

Why are the feathers on your throat red?

I say that is only for my mate to know.

How would your mate know?

My mate would not have to ask.

3.

Weary of your eyes,

I introduce you to Python Woman.

Her grip, you mention, is impressive,

as is the overlapping leather of her scales,

but you find her endless bunching

and uncoiling unnerving. And the skins

all over her floor, just bad housekeeping.

Venom clings to every fiber.

It will take weeks to rid the smell

from your clothes.

4.

The first time you touch me is an accident.

We are laughing together,

as though you are not only interested

in my hollow bones or my tendency to molt

before I go onstage.

As though you would with anyone,

your hand reaches for me, eyes snapped

tight as two lids over jar mouths

your fingers graze a feather—halt

when they remember.

5.

I’ve seen you sitting mostly naked

patching together found feathers.

Are those supposed to be ________?

6.

The ringmaster wants you to leave.

The bloodcoils around her eyes

convince you it is, in fact, time to go.

She sends the twins to watch you pack.

They argue over what kind of business

you might try that would be considered funny.

7.

You want to know the future.

Will I see you again?

Uncertain.

Do you feel anything for me?

I do not know.

Anything?

I tilt my head and do not blink. You hate that.

Then, goodbye.

I look to the sky, smell rain.

8.

Why I no longer fly:

From here, it is the same view.

Everyone is a fossil,

excavated marionettes breaking

through crests of earth.

From here, a collection of upturned

eyes is a light show splayed

over uncut stones.

Here, we are all seraphs caught

in a mist net, and left

abandoned by the sky.

from on .

________________________________________________________

Affrilachian Poet and Cave Canem Fellow, Bianca Spriggs, is a multidisciplinary artist who lives and works in Lexington, Kentucky. The author of Kaffir Lily and How Swallowtails Become Dragons, Bianca is the recipient of a 2013 Al Smith Individual Artist Fellowship in Poetry, multiple Artist Enrichment and Arts Meets Activism grants from the Kentucky Foundation for Women, and a Pushcart Prize Nominee. In partnership with the Kentucky Domestic Violence Association, she is the creator of “The SwallowTale Project” a traveling creative writing workshop designed for incarcerated women.

Trick Vessels, by Andre Bagoo

Shearsman Books, 2012

ISBN 978-184861-203-7

Reading Andre Bagoo’s Trick Vessels incites a strange and rather silly first thought: “the imperative sentence wages a huge comeback!” Dumb thought? Being kind to myself (a favorite past time of mine) I begin to scratch this first thought for its complexity:

A. There is no greater or more compressed ordering device in the grammar of English than the imperative sentence.

B. It is the God sentence, and thus noun may be swallowed up in verb, and understood through action: Go! Leave! Look! Let!

C. There is much authority in the imperative. Eliot, knowing this, blasphemed against that authority, and gave it an ironic twist in Prufrock, that prime example of modern urban equivocation and enervation: “Let us go then, you and I.”

D. This much authority in a post-structural age, used without irony, is a huge gamble. After all, are we all not relativists, masters of the “but, perhaps not”, whores of the non-authoritative. After all, are we not men- kinda, sorta, well… really not? Isn’t our language always correct, and non-committal? Aren’t we sensitive and caring, and “Aware” and “grocking” even as we aim our drones at lil children, and assorted other enemy combatants?

Damn, straight! (well, maybe…). The first poem in Bagoo’s Trick Vessels doesn’t only use imperatives. It uses God’s imperative: Let. Unlike Prufrock, it is not immediately undercut and sabotaged by equivocation. This is the precise, intense, unequivocal imperative of ancient poesis: the poet conjuring the world, making it up as he/she goes along, taking on the authority of a lower case god:

Let the daughter of the Hibiscus say: “His love has no end.”

This is let restored to the full, non-ironic, authority of invocation, and, reading the poem, I wonder if Mr. Bagoo might not be a believer as well as an anti-ironist. But the poem is too tricky to rate a mere Christian wave. According to the poem, this love that has no end is a flower, and that flower is night, and hence the title: The Night Grew Dark Around Us.

I think of that trickster, Bob Dylan, informing us: “it ain’t dark yet, but it’s getting there.” I do not think this is the same dark as Dylan’s sinister version. The Poet’s dark could perhaps be not unlike St John’s “Dark night of the soul.” It could be the dark of his skin, of his ancestor’s skin, the dark ripped from its negative relationship to light, and turned into its own species of light dark as a form of light? This is not at all unusual with poets of a mystic turn, nor is it unusual with poets under historical crisis and duress (consider Miguel Hernandez writing from a dank Franco prison: “I go through the dark lit from within.”).

Perhaps this night which is flower which is love is a wager, a leap into the absurd. A decision to trust darkness itself as the percipient condition out of which light comes and to which it returns. Night in the sense of love is tomb and womb as one, and reading deeper into Trick Vessels we find this sense of dark, of erasure, of trickery to be what the great critic Kenneth Burke called “Equipment for living.”

The trick vessels could be the slave ships, but, being trick vessels, they shape shift and are never one thing, never condemned to an absolute definition. If they must be identified, the trick vessels are the words of the poems themselves, the words of invocation, of magic, of night. Let us consider night first:

IV On Encountering Crapauds at Night (from the poem, Trick Vessels):

I’ve grown to love the backs of Crapauds/That hide in dark spaces between steps/

And bow as though at temple.

And on trickery (Part VI):

The fig tree could be a murderer

A bandit come to ambush.

And later in the same section:

A soft whisper can bite.

A world of murdering fig trees and biting whispers is a world in which things can be counted on to have no loyalty to seeming. It is a word of shape shifting, a tricky world of night and, in such a world, the only true ordering intelligence is invocation—the authority of words as magic, as act—as incarnation. In such a world, “let there be” without irony is still warranted, still efficacious. In such a world where soft whispers bite, language does not resort to irony, to the glib, to the entitled, the privileged, the self referential. It is a matter of life and death, a matter of the right spell at the right time, a ceremony of erasures against erasure. Night may efface night and not be lost. The light of day has no such power, cannot live in erasures, and must resort to Prufrock’s whining equivocate: “that is not it at all.” Protest here is swallowed up in the medicine and strength of words as an act of majesty.

Much magic thinking runs up against rather brutal modern realities (Bagoo is also a journalist in Trinidad), but this is not the magic thinking Eliot would have condemned as Prufrock’s form of “Bovarism.” Instead, these words of night are as vessels, as ships, a ceremony of journeying where the Unnamed Creature Said to Come from Water (Title of the second poem) assures us:

But I have such knowledge, /I ensure these erasures/I follow the stop. I do not leak.

Broken Vessels then moves from certainties to uncertainty in many respects (as erasures tend to do), but out of this shape shifting, this world where soft whispers bite comes a new dynamic. It may be expressed as: I may not exist, and you may not exist, but what exists, and what can be trusted in the ongoing dynamic between the you and I. Sure enough, in the poem, Preface for Seasons the voice of the poem addressed a “you” to which it is in relation. The seasons here as mainly liturgical, seasons of ceremony: Advent, Epiphany, Lent, Holy Week, Easter, Ascension, Pentecost (ordinary time is, as with most poets, left out). These are Catholic, but Catholicism is here but a form under which deeper orders hide and are enacted:

Some Lines from Advent:

There is a church inside a church/Where a mountain clump breaks off

And then from Incarnation:

Becomes a tree/the tree that breaks free/to become a ceremony

(note how this echoes the opening transubstantiation of love into flower into night. Trick Vessels is full of transformations under the signs of night, ocean, and the ongoing shape shifting of identity and politics).

From the section called Lent:

The values becomes valueless/ The desired is at first rejected/ the reject is later consumed.

This is a trick in theology known as transvaluation of values: the mountains are brought low, and the valley raised, the rich are brought low and the poor exalted, the valued becomes valueless, and the desired is rejected.

From Holy Week:

Thousands of touching hands/covers for secret agents

The praising mob that touches becomes the mob shouting crucify him. Judas betrays with a kiss.

From Easter (the shortest and most cryptic of the sections):

In between dreams/I make sense/In waking life/Chaos is hard to prove.

Chaos is not hard to prove in the night, and in the dark night of the soul, chaos is the only true order—the complex order of what has been lost and what might come to be—percipient order, the chaos of da Vinci’s deluge sketches—not void of order, but order as yet undetermined. We must resist the too easy chaos of contemporary life for it is not chaos but merely the random, the arbitrary, and these poems while shape shifting, call on something more than the arbitrary life. They call on ceremony. The poems of Trick Vessels are not the imposed order and false certainties of neo-conservatism, but an embracing of the power and force of night through the spell casting power of language–the magic that does not destroy uncertainty but which gives it value, and purpose. Because Bagoo’s poems do not traffic in false certainties, they restore the authoritative voice to its poesis—its intimacy with the dark, with the shape shifting upon which the poet’s older right to invoke most firmly rests.

In a larger sense, beyond the book, I see in Bagoo’s poetry a moving away from the equivocations of the best who lack all conviction and beyond the worst who are full of a passionate intensity. The poems in this book represent a movement away from equivocation, from irony, from the parody, the self-referential, towards a more genuine formalism—not the somewhat neo-conservative formalism of Hacker or, more so, the cranky formalism of metricists, but an older sense of poetry as the enacting of a ceremony, a vital and rhythmic invocation, almost liturgical in its use of the imperative, and the invocative. It is the genuine precision and formalism of spells, of prayer, or rhapsodic speech, a ceremony which must be formed out of the utterance itself to “order the sea.”

Bagoo might strike some as too sincere, as too insistent in his intensity. He uses anaphora, the imperative, the list, the rhetorical tricks of mystical oxymoron, and of transvaluation–all the tools of the magic trade—of invocatory speech. He undercuts such tricks at times with news from the world, but the world does not triumph over the verbal will here. These poems, as I said, are very formal in terms of their deliberation and engagement. Unlike the neo-formalists they are not about rhyme, meter, intellectual display or emotional detachment. Bagoo does not impose wit and order upon the landscape. He is not the return of Auden. He is, in a sense, the return of that which “Sang beyond the genius of the sea.” His is an ordering intensity—a ferocity of engagement which is always, by its nature, a thing of ritual. “A ceremony must be found” John Wheeler, the poet, wrote some eighty years ago. Bagoo has found that ceremony in this fine collection of poems.

There are certain (uncertain) propositions that every poet must eventually encounter, if only to embrace or abandon. They are not propositions so much as ways of being, lifestyles; and, like the way one walks, or talks, or just stands in the rain, they are ineluctably intimate parts of ourselves, hence not propositions so much as self-images. What kind of poet do you want to be (I imagine a Bellovian unctuous trickster asking)? What kind of poet are you?

“Oh, she’s an angry poet,” they say, or, “The woman is far too sentimental for my tastes.”

These are cursory judgments, but some kind of truths are lodged in even the most mawkish and unhelpful of sentiments. So let’s begin at the beginning. A poem is a stance, a temperament, a philosophy, an ontologically practical, (if impractical), modus operandi. A vision – not necessarily metaphysical, but a way of looking at things that is that particular poet’s way. The proof? An Ashbery poem is not a Creeley poem. Read an Ashbery poem. You might immediately conclude that Ashbery is a funny poet, a strangely poignant poet, a curiously flat poet, like Warhol, or Clare, a poet of disappointment, a poet whose science entails the combining of words and phrases that, without Ashbery’s florabundant consciousness, would never have been placed together in the first place. Ashbery is a poet of surprise, of flow, a John Cage of language, whereby the chance coincidences of daily stuff form an abstract collage that is life heightened: an aesthetic.

Is Creeley – I’m thinking of early Creeley, from For Love – the (complex) opposite of Ashbery? What do Ashbery and Creeley share besides a certain kind of disappointment, a disillusionment with what Richard Rorty calls “the way things hang together”? For, aside from this initial bewilderment or despair at the way things are – ontologically, epistemologically – Creeley is the poet of the anti-flow, the inept and inert stutter, the desperation of someone who cannot say what he wants to say, so makes a poem out of that. To say that Creeley is funny is like saying that Todd Solondz’s movies are funny. For Creeley’s early poems are often cruel, and to say that they are “funny” is perhaps to say more about your own predilections for mean-spiritedness than, say, Creeley’s.

Still, like Ashberys’ early work, Creeley’s poems are, or at least seem to be, something new. They are not exactly adventures of the imagination, like Ashbery’s; in fact, I wonder if the word “imagination” is even appropriate for discussing Creeley’s early works. For if Ashbery’s philosophy is “Perhaps we ought to feel with more imagination,” Creeley’s is, “Perhaps we can’t feel with more imagination.” Yet does that make for a coherent, or even interesting, poetics? If Ashbery’s poems are premised, if distantly, on a hope for the future, a hope for new imaginary communities, a hope for a new way of speaking, Creeley’s poem are cynical about the future, isolated from community, and unable to even speak.

It is for that reason, paradoxically, that they deserve some attention.

For the point of comparison, let’s look at two poems: one by Ashbery, one by Creeley, both with the same titles – “The Hero” – and from their first well-received books – Some Trees, by Ashbery, published in 1956, and For Love, by Creeley, published in 1962. I want to interrogate, foremost, how Ashbery and Creeley conceptualize their heroic figures, for in scrutinizing such humongously important matrices of ideas, we might therefore put our finger on the nerve, not only of what makes these poets so different, but also on how we might characterize and define their individual and idiosyncratic poetic (and therefore philosophic) stances.

Here is Ashbery’s “The Hero,” in full, (and notice the interestingly Creeley-esque form):

Whose face is this

So stiff against the blue trees,Lifted to the future

Because there is no end?But that has faded

Like flowers, like the first daysOf good conduct. Visit

The strong man. Pinch him –There is no end to his

Dislike, the accurate one.

We might start by acknowledging how enigmatic the poem is – even, perhaps, how willfully obscure. Who is the eponymous hero? Is it the “stiff” face, “lifted to the future”? Is it “the strong man”? Is it “the accurate one”? All three? Is the poet himself the hero, and is his stance the one which we might take to be heroic? If so, how would we characterize his stance towards the “hero”?

Let’s try a thought experiment. Imagine that Ashbery’s “hero” in this poem is Robert Creeley. And imagine that Ashbery, like any competitive poet – locked in some regards into a good old fashioned Bloomian agon – wishes to carve out his own poetic voice in contradistinction to Creeley’s. How would this affect our reading of the poem?

First, perhaps Ashbery would be mocking, however quietly, Creeley’s “stiff face,” the unyielding way in which he denies all transcendence – not because Ashbery believes himself in transcendence, but because of the way in which Creeley denies it – so stern, so puritanical, so unbending. The “blue trees” might then be a trope for Ashbery’s poetic persona. In many poems in Some Trees – “Two Scenes,” “Popular Songs,” “The Instruction Manual,” “Meditations of a Parrot,” “Sonnet,” “Le livre est sur la table” – the color blue figures prominently and enigmatically: we hear of “the blue shadow of some paint cans,” “the blue blue mountain,” a “rose-and-blue striped dress (Oh! such shades of rose and blue),” “blue cornflakes in a white bowl,” “the razor, blue with ire,” and a “young man” who “places a bird house / Against the blue sea.” Blue trees are especially poignant, considering that the title poem of the book, “Some Trees,” is about trees as a metaphor for human connection. So maybe equating the blue trees with Ashbery’s poetic persona isn’t as hackneyed as it sounds.

But where does that take us? Is the face “lifted to the future,” or are the trees? Perhaps we might read the second stanza in two ways. If “no end” refers to the trees, then we might read the phrase as a typical self-referential Ashberian commentary on the elasticity of time. But what if it is Creeley’s face – a very distinct one, considering he had only one eye, and occasionally wore an eye-patch – that is raised to the future? Might we then read “no end” in completely different terms, as a kind of complaint, as if to say, “there is no end to my suffering”? We might then have the same tension in the first stanza – Creeley’s face, stiff against the blue trees of Ashbery’s persona – repeated in the second, where Ashbery is ridiculing Creeley’s stance as pompous and self-aggrandizing, as one who laments the endlessness of suffering and who must look (mawkishly), as a result, to the future, where perhaps there will be less pain.

Now let’s follow our divergent readings and see where they take us. If we read the next three lines – “But that has faded / Like flowers, like the first days // Of good conduct” – as more typical Ashberiana, then what we have on our hands is the Ashberian mode of replacing one image as quickly as he can with the next, as if we were reading a Stevens poem set to fast forward. But what if what’s faded – what Ashbery is arguing for – is the Creeleyan poetic stance – the cynicism, the disgusted high-mindedness, the seriousness, the darkness? Is this perhaps the moment at which Ashbery begins carving out his own poetic identity, by critiquing his reading of Creeley’s poetic identity? If so, then we might paraphrase those three lines as saying something along the lines of, “Yet your stance, for all its professed heroicisim and stoicism, has already faded like flowers, or childhood days when we cared about our behavior.” In this sense, Ashbery would be arguing that Creeley’s stance – perhaps like Lowell’s – is outmoded, and therefore not a viable aesthetic, at least for Ashbery.

In the final lines, therefore, we are faced with a massive ambivalence. For it is unclear if “the accurate one” is Ashbery or Creeley. We therefore do not know if this “dislike” is being criticized or commended. If we read “the strong man” as the Creeleyan poetic persona, then we might read the final lines as Ashbery critiquing Creeley’s misanthropic dislike, his fastidious need for accuracy. Yet if we read “the accurate one” as Ashbery, we might read the final lines as a self-critique, with Ashbery uncomfortable with his criticism of the strong man – i.e. the pronoun “his” in the second-to-last line would be Ashbery, and here we would hear Ashbery’s own exasperated sigh with himself. The point is not to find the exact right reading, but rather to call attention to the way in which, in Ashbery’s “The Hero,” these ambivalences are braided together. Yet it seems intriguing, to say the least, that “The Hero” is written in such characteristically Creeleyan form.

Now let’s look at Creeley’s “The Hero,” made up of eleven four-lined stanzas. How does Creeley’s stance towards the hero in his poem differ from Ashbery’s? Here is the whole poem:

Each voice which was asked

spoke its words, and heard

more than that, the fair question,

the onerous burden of the asking.And so the hero, the

hero! stepped that gracefully

into his redemption, losing

or gaining life thereby.Now we, now I

ask also, and burdened,

tied down, return

and seek the forest also.Go forth, go forth,

saith the grandmother, the fire

of that old form, and turns

away from the form.And the forest is dark,

mist hides it, trees

are dim, but I turn

to my father in the dark.A spark, that spark of hope

which was burned out long ago,

the tedious echo

of the father image– which only women bear,

also wear, old men, old cares,

and turn, and again find

the disorder in the mind.Night is dark like the mind,

my mind is dark like the night.

O light the light! Old

foibles of the right.Into that pit, now pit of

anywhere, the tears upon your hands,

how can you stand

it, I also turn.I wear the face, I face

the right, the night, the way,

I go along the path

into the last and only dark,Hearing hero! hero!

a voice faint enough, a spark,

a glimmer grown dimmer through years

of old, old fears.

The poem begins with the asking of questions – what seem important questions, for those who answer the questions are aware not only of the question themselves, but the “onerous burden” of asking. There is therefore a dialectic that is set up between questioning and asking, both activities which, as the poem continues, are anointed somewhat with heroic status, and given metaphoric clothing as adventures into the dark.

Yet we do not hear of this heroic adventure being undertaken by the hero him or herself. Rather, the hero, who disappears as a figure after the second stanza, and is replaced with the poet himself, does his vague heroic deed, and thereby lives or dies accordingly. Although it is difficult to read the tone of the second stanza, Creeley exhibits a certain sad insouciance towards the hero, as well as a disconnect towards the hero’s fate – i.e., he or she will either live or die, but either way, Creeley seems to be saying, these are the typical conventions of a heroic story, and there is nothing surprising about that. Here the speaker’s relationship to the hero is different from the Ashberian speaker; it is more straightforward, if similarly, though less complexly, ambivalent. In Ashbery’s poem, despite the title, it is never clear just who the hero is, so we are adrift upon a vague ocean of resemblances and concordances; in Creeley’s poem, it is more clear that the hero is the conventional hero of fairy tales, venturing off into the dark forest, but it is also Creeley or the poet himself, venturing similarly into the tangled thickets of memory, to try and devise a way of forming something lasting from this adventure, some redemptive offering, a poem perhaps. In this sense, Creeley’s poem is less ironic than Ashbery’s. It does not truck in a difficult-to-place irony, nor does it use discordant and puzzling imagery that entails a kind of cognitive dissonance for the reader. If anything, Creeley’s imagery – though his style still somewhat beguiles – is largely conventional: we have the hero, the dim dark forest, the grandmother urging the hero out, the father figure, the quest, night and light, the path. This all sounds rather yawn-worthy, however; so what is it that makes Creeley’s poem interesting?

What makes Creeley’s poem interesting is that, for all its stylistic compression, we are given a very standard and conventional narrative; and despite the tone of exhaustion and cynicism we might feel from the speaker towards his subject, Creeley does not revise the heroic quest story very much, or offer very many alternatives. Another way of saying this is that Creeley, and the Black Mountain tradition he emerges from, does not do irony. Creeley’s hero, therefore, is the hero of myth, of fairy tale and folk tale; and we might do well to read much of his work, consequently, in that light – as work in which Creeley posits himself as the conventional male hero figure, and all his various disappointments in love as commentaries on this figuration. This might make some sense, considering Creeley’s later work, where much of his intriguing bitterness is replaced with a kind of lazy contentment that seems to suggest an end-of-the-road poetics, whereby the earlier misanthropy of the young man is replaced with arm-chair speculation and hard-earned domestic satisfaction.

All of which is to say, that Ashbery, after this analysis, strikes me as the more radical poet. His poem takes greater risks – earlier we called it “willfully obscure” – but Ashbery does not seem saddled so much with the desire to be the Promethean quester, searching for the fire, venturing into the forest. He’s way too ironic to take these myths too seriously, although he’s radical enough to substitute new imagery for old. For that reason, if Creeley sees himself as the king of his own narrative, questing after redemption, where he will either live or die, Ashbery once again finds himself in the role of trickster and clown, discombobulating our awareness, turning our attention to his motley theatrics, and poking fun at convention. The New York School, if we wish to place Ashbery in that context, is far, far more ironic. If we wish to understand more deeply the relationship between the Black Mountain poets and the New York school, then, we might start by investigating and interrogating the role that irony plays in much of these poets’ works.

dream in which you survive and in the morning things are back to normal

except, I found tufts of fur at the foot of

the bed _____my muscles bruised beneath

cracked bone _____I thought we were walking

through the woods ___ standing not-close

enough while I tried to find something to pull

from my mouth _____ something that would make

sense ___the ease in which my love for

almost everything folds into itself hard with

waiting _____there was salt in your eyes

my nail beds ached, dull at first ___my mouth

burned with iron ____a small guttural noise

kept spilling __and you ran and wouldn’t stop

_______ and you wouldn’t even turn back

_______________________________________________

Aricka Foreman is a Poetry MFA candidate at Cornell University. A Cave Canem fellow, her work has appeared in The Drunken Boat, Torch Poetry: A Journal for African American Women, Minnesota Review, Union Station Magazine, Bestiary Magazine, and Vinyl Poetry. She is a Poetry Editor of MUZZLE Magazine, and Assistant Editor of EPOCH. She is originally from Detroit.

The Eggshell Parade brings you a reading and interview from poet Michelle Bitting. Michelle reads .

Massachusetts writers hold a great position of influence in American writing. Some of this is just a matter of timing: Massachusetts had a kind of head start in fostering talent, and such advantages inevitably become influence (“whosoever hath, to him shall be given, and he shall have more abundance”). But perhaps it’s better not to speak of “influence”; instead, I would claim that Bradstreet divined in the landscape images and structures of being that other American writers would discover and explore.

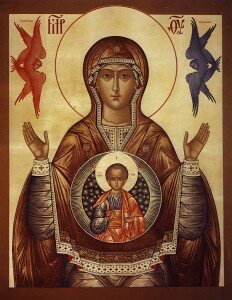

After pondering the act of contemplation, Bradstreet retells the first murder. Cain is depicted as the definitively anti-Christ figure, a cursed newborn enthroned in the lap of Eve (contra images of the theotokos):

After pondering the act of contemplation, Bradstreet retells the first murder. Cain is depicted as the definitively anti-Christ figure, a cursed newborn enthroned in the lap of Eve (contra images of the theotokos):

Here sits our grandame in retired place,

And in her lap her bloody Cain new-born;

The weeping imp oft looks her in the face,

Bewails his unknown hap and fate forlorn;

Stanza 15 tells the story of Abel’s murder:

There Abel keeps his sheep, no ill he thinks;

His brother comes, then acts his fratricide;

The virgin Earth of blood her first draught drinks,

But since that time she often hath been cloyed.

The wretch with ghastly face and dreadful mind

Thinks each he sees will serve him in his kind,

Though none on earth but kindred near then could he find.

This is the bloody inevitability that Frost explored in poems like “Design.” But in addition to her distinctly Massachusetts sensibilities, one can find a propensity toward that broader, particularly American expression of the doctrine of original sin: the social outcast set adrift in a vast and bleak landscape. Stanza 16 describes Cain’s punishment:

His face like death, his heart with horror fraught,

Nor malefactor ever felt like war,

When deep despair with wish of life hath fought,

Branded with guilt and crushed with treble woes,

A vagabond to Land of Nod he goes.

A city builds, that walls might him secure from foes.

Cain is literally branded by God–a marked man, harried by his curse. He is a builder of defensive cities in the wildernes. He cannot farm fruitfully (the ground that drank the blood he spilled refuses him). He lives in constant fear of attack. It is notable that when Bradstreet contemplates sin (something that must be confronted when asceding to God), she does not identify with Adam and Eve, the traditional figures of original sin but with their cursed child. It is easy to forget that there are two events of ‘casting out’ in the first three chapters of Genesis: first, Adam and Eve, cast out for the “spiritual murder” of humankind, and second, Cain, cast out for the literal murder of his brother Abel.

While the marked outcast has been a perennial theme of literature (e.g., The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, etc.), it has found particular resonance in American literature, particularly American literature of the West. My point is not that Bradstreet established the theme of Cain and Abel that later American writers picked up. I suppose it’s possible, but I think it’s much more interesting to say that there’s something in the American landscape and founding psyche, a kind of inverse of the “city on the hill.”

The story of Cain is built into the founding mythos of America, whose people were cast out of Europe to violently master “uncivilized” land (as de Tocqueville observes, “the happy and the powerful do not go into exile”). Consider Moby-Dick, which, despite being set on the ocean, is arguably a story of the proto-modernization of the American west. Like the descendants of Cain, who first use bronze and iron, whaling ships are mini-factories that subdue and process the raw materials of industrialization. A more recent book that memorably retells the myth of Cain in the American context is Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian. McCarthy’s Kid, born with an appetite for blood, “a mindless taste for violence,” is the quintessential marked outcast, “branded with guilt” and pursued by the Judge (a kind of Nietzschen Satan).

Bradstreet’s poem also gestures toward another notable American obsession: Armageddon.

THE FLESH LUSTETH AGAINST THE SPIRIT

This move to the story of the fall and the first murder are necessary for Bradstreet. Being on the edge of what she knew as civilization, Bradstreet had many chances to reflect upon and enjoy the sights of nature. But one who enjoys nature as she does inevitably confronts the ontological fear of death, the finality that nature itself circumscribes. Human persons are driven by appetites, the “delectable view[s]” that enrapture the senses: these passions are primal, the defining experience of embodied beings–we associate them with life, with vitality itself. But they are also fickle, insatiable in any ultimate sense (“Hell hath no limits nor is circumscrib’d”), and, as both ancient Greek and Chinese philosophy realized, the “untutored” pursuit of the passions enslaves us because it places us in a dimension of constant reflexivity, never resting. This is one of the themes of stanza 17:

And though thus short, we shorten many ways,

Living so little while we are alive;

In eating, drinking, sleeping, vain delight.

So unawares comes on perpetual night.

And puts all pleasures vain into eternal flight.

Human life, already a flash, is lessened by pursuit of life. Night comes and satisfaction recedes into its “eternal flight.” In a manner worthy of Solomon, stanza 17 treats of the vanities of human action and pursuits. And also like Ecclesiastes, this recognition moves the poet to consider how the man’s fleeting pursuits contrasts with the seeming inexhaustability of nature (“One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh: but the earth abideth for ever.”). The result of this is stanza 18, which, for my money, is one of the more beautiful articulations of the mystery of death in English:

When I behold the heavens as in their prime,

And then the earth (though old) still clad in green,

The stones and trees, insensible of time,

Nor age nor wrinkle on their front are seen;

If winter come and greenness then do fade,

A spring returns, and they more youthful made;

But man grows old, lies down, remains where once he’s laid.

There are possible echoes of Milton here, but the poem undoubtedly ends with Job:

For there is hope of a tree, if it be cut down, that it will sprout again, and that the tender branch thereof will not cease. Though the root thereof wax old in the earth, and the stock thereof die in the ground; Yet through the scent of water it will bud, and bring forth boughs like a plant. But man dieth, and wasteth away: yea, man giveth up the ghost, and where is he?

In both Ecclesiastes and Job, as well as in Bradstreet, humanity’s ambition to sate its appetites by nature manifests the limits of human persons, exposing the meaninglessness of such pursuits  (“the eye is not satisfied with seeing, nor the ear filled with hearing.”). The depthless void of man’s appetites cannot be filled, even by nature’s unending renewal: this is the sum of ancient wisdom literature. The pain of this realization, profound as the insight is, cannot lead to Bradstreet’s deep “groan in that divine translation” (the piercing and painful sweetness of holy ecstasy). Such a conundrum forces the question: if man cannot be sated by nature, what can possibly fill him? The obvious answer is God–but Bradstreet does not go there quite yet.

(“the eye is not satisfied with seeing, nor the ear filled with hearing.”). The depthless void of man’s appetites cannot be filled, even by nature’s unending renewal: this is the sum of ancient wisdom literature. The pain of this realization, profound as the insight is, cannot lead to Bradstreet’s deep “groan in that divine translation” (the piercing and painful sweetness of holy ecstasy). Such a conundrum forces the question: if man cannot be sated by nature, what can possibly fill him? The obvious answer is God–but Bradstreet does not go there quite yet.

Rather than turning to God, she moves to the undoubtedly zen image of the river: as Siddhartha perfectly demonstrates, the river is an image of the emptiness of Nirvana; it is present at its beginning, middle, and end, and, confounding time, is thus outside of time. It has escaped the vicissitudes of life and therefore can be said to be unchanging, without desire, passionless. Bradstreet addresses the river as “Thou emblem true of what I count the best.” In the river, Bradstreet observes, fish naturally do what they should: “So nature taught, and yet you know not why, / You wat’ry folk that know not your felicity.” The fish is zen; I’m reminded here of Chuang Tzu’s poem, which Merton translated as “The Joy of Fishes.” But, of course, the fish is doubly symbolic as it was the symbol of early Christians. Inasmuch as Christians participate in the life of God, they share the joy of fishes, living in “the peace of God, which passeth all understanding.”

All ascetics must go “through the river,” so to speak. Having pierced the wisdom of the river, Bradstreet’s soul is now ready for its final ascension:

While musing thus with contemplation fed

And thousand fancies buzzing in my brain,

The sweet-tongued Philomel perched o’er my head

And chanted forth a most melodious strain

Which rapt me so with wonder and delight,

I judged my hearing better than my sight,

And wished me wings with her a while to take my flight.

For Augustine, sight is the sense of sensual perception (“the lust of the eyes”). Hearing, however, is the sense of faith. Christ told doubting Thomas “blessed are they that have not seen, and yet have believed.” And Paul says “and how shall they believe in him of whom they have not heard?” In Bradstreet’s Christian tradition, God is not made perceptible through sensual perception (“Thou canst not see my face: for there shall no man see me, and live.”), but only through the testimony of others, through hearing. Bradstreet has been seeing this whole time, observing nature and pondering its sights: this has prepared her heart for what comes by another sense: her soul in the proper state, having reached a sort of Nirvana by the river, can now clearly hear the call of her master’s voice and follow that voice “into a better region, / Where winter’s never felt by that sweet air legion”.

Bradstreet ends the poem, appropriately enough, with an image from Revelation: “he whose name is graved in the white stone / Shall last and shine when all of these are gone.” This is appropriate not simply because it is the end of the poem, the unveiling of all things, but because it channels the apocalyptic geist that has been with America since its inception. The vast and final regions of the United States opened before man a final panorama over which to play out his desire to consume nature. This forces mankind as a whole, like the author of Ecclesiastes, to the “overwhelming question”: “Is there any thing whereof it may be said, See, this is new?“ Or, in other words, what possible thing after this? In the narrative of growth and exploration, America is–in a sense–the last step before that narrative ends or must reinvent itself.

AND THEN WE SAW THE DAUGHTER OF THE MINOTAUR

Poet, comma. It is thus the delay,

which is also a beginning. That we can link eyes

across her time-space continuum is another hyena.

The female elongates, bares fangs, and a trash

compactor recycles. Hyena gives

in the recycling fashion. Phoenix, no more false

flight from holes; now balloons eat at decay.

Hunger denuded us, too. But will you give

up your death for me? With surgery, I outright hollow

the monster to breathe across windows. I don her hollow

whole. She writes back in the pauses of haze.

Her and her tragic magic. We are all cross-dressing

in tiny wings with the machines of bones to go on.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tRjYIPLUiKY&version=3&hl=en_GB]

___________________________________________

Of her most recent book from Litmus Press, I Want to Make You Safe, John Ashbery described Amy King‘s poems as bringing “abstractions to brilliant, jagged life, emerging into rather than out of the busyness of living.” Safe was one of the Boston Globe’s Best Poetry Books of 2011, and it was reviewed, among others, by the Poetry Foundation and the Colorado Review. King co-edits Esque Magazine and the PEN Poetry Series with Ana Bozicevic, has conducted workshops at such places as the San Francisco State University Poetry Center, Summer Writing Program @ Naropa University, Slippery Rock University and Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), and interviews for VIDA: Woman in Literary Arts. She was also honored by The Feminist Press as one of the recent “40 Under 40: The Future of Feminism” awardees and received the 2012 SUNY Chancellor’s Award for Excellence in Scholarship and Creative Activities.

The Mimic Sea

By Erica Bernheim

42 Miles Press, 2012

ISBN 978-0983074724’

I hope the Monarch butterfly I released this spring landed in Mexico tagged with

the ending line of the opening poem of Erica Bernheim’s Moonrats:

I’ve got rights and I should look into them.

This is the fewest of the “first books” I’ve read that feels completely self-interrogated and worked upon. It shines and it never presumes its own rescue. Dear Baby, I am held up/by anchors and antlers: one holds me down, the other/keeps me alone. There are statements all over this collection one could theoretically hear from NBC News’s Foreign Correspondent Richard Engel if he’d been released from captivity after five years instead of five days. Laid end to end, seven million hummingbird/eggs will take you to the bus stop and back. Ask the bodies I stand beside on any public transportation and they’ll tell you: I don’t toss about a term like interiority often.

Opening of The Superstition of the Clean Glass:

A cross-section of a tough person seems/touched in the middle of an island, and/we like it.

Bernheim’s is an interior lyric, on par with the elegiac verse of the late Larry Levis. Reading this book is not dissimilar to overhearing a soliloquy on intimacy pieced together by tape-looped recordings of “empty” residences visited and perturbed by The Atlantic Paranormal Society. I miss part-time investigator Donna, who also used to run the Ghost Hunters front office. Sometimes the Connecticut female accent is the only reason I remain in this country.

There’s a newer lyricism stirring around and around the Large Hadron Collider Chamber.

The newer lyricism is more about vibration and less about experience and feeling, experience and feeling having gotten humans squadoosh. This book continually reminds me buoyancy is better than tone, or being right. Bernheim challenges her reader to be intimate. She’s going to be intimate whether you choose to participate or not. I tried to impart to my Navy town how high on the courage-scale that ranks, but most of my neighbors care more about watching me fall off the fiscal cliff.

In the poem Fifteen Beautiful Colors, Bernheim examines light. I didn’t think that kind of magnification was possible anymore in poems.

XII. Two arms reaching make little sound grasps at smoke.

Nothing here will/bloom or rise, planetary faces.

Speaking of light, whenever sunlight is mentioned, something terrible has happened or something wonderful is about to happen. I love that. Prediction: Bernheim will win the third season of Spike TV’s Ink Master. Her championship tat will be whatever life form eventually emerges from Saturn’s moon Enceladus. She’ll pull on host Dave Navarro’s goatee and it will come off. As Ink Master, she’ll tattoo whoever she wants whenever she wants however she wants. As Ink Master client, my mother may desire three-dimensional Wedgwood buttons on her eyelids, or nipples? I’m praying for behind the calves, Mama.

I want the following gem from the poem Dialogue for Robots (pg. 67) tattooed on my pelvis:

In front of our eyes are too many ways to breathe.

It’ll be a cover-up for the botched Soul Train choo-choo.

There are poems addressed to a day-lily, a zookeeper, and a bellhop in here. They’re all provided the same equality of respect.

Let’s dig deeper into the Bernheim/Levis comparison. Here’s three lines. Pick which ones are Bernheim and which ones are Levis:

We go & there’s no one there, no one to meet us on the long drive lined with orange trees

You can recognize the words and not understand the sentence.

Put me in a scene and watch as nothing changes.

Try these:

It’s like your bones died two weeks before you did.

We was just two tents of flesh over bones.

Sex should be no more important than a glass of water.

Don’t worry, Good Will Hunting is still working all this out too.

Having appeared in the 2006 anthology Legitimate Dangers, Bernheim legitimately waited nearly two presidential terms to publish this full-length collection in 2012. She took her sweet time, I suspect, in order to release something rare, special, and dangerous — a finished book.

The assertion that “Contemplations” is primarily concerned with the ascension of the soul may bump against prevailing notions. Some critics have said Bradstreet was more in love with the earth than heaven since the lines that directly address the idea of heaven often fall short: “too often merely traditionally rendered passages pale before some of the more deeply felt lyrical passages in praise of Phoebus and the things of earth”. Indeed, the poem begins with the rapture of the poet as she views nature: her gaze begins with the autumn leaves, then moves upward toward the sun:

Thou as a bridegroom from thy chamber rushes,

And as a strong man, joys to run a race;

The morn doth usher thee with smiles and blushes;

The Earth reflects her glances in thy face.

Birds, insects, animals with vegative,

Thy heat from death and dullness doth revive,

And in the darksome womb of fruitful nature dive.

“More heaven than earth was here [on earth]” Bradstreet says. In fact, stanza 8, which immediately follows a four stanza paean to the sun, seems to contain Bradstreet’s inadvertent admission that she cannot express genuine feelings about God, as opposed to her clearly inspired stanzas about nature:

Silent alone, where none or saw, or heard,

In pathless paths I led my wand’ring feet,

My humble eyes to lofty skies I reared

To sing some song, my mazed Muse thought meet.

My great Creator I would magnify,

That nature had thus decked liberally;

But Ah, and Ah, again, my imbecility!

Bradstreet is clearly not describing nature anymore any more than she is bushwacking “pathless paths” through the forest. She is traveling an inward landscape now. This stanza and the ones that follow are a flock of neo-Platonist images. Gazing toward the (inward) sky, her Muse thinks it appropriate to inspire song. And yet, divine though the Muse may be, Bradstreet is unable to perform. Is it because Bradstreet harbors the unspoken belief her ecstatic paean to the secular cannot match what she is able to say about the sacred? To me this interpretation only resonates if you harbor the assumption that the one need crowd out the other. But in Hopkins, for example, the ecstasies of the “secular” are sacred. Think how seamlessly Hopkins moves from the image of the dawn to the Holy Spirit and back to nature again in “God’s Grandeur” (another poem that shares many affinities with “Contemplations”):

And through the last lights off the black West went

_____Oh, morning, at the brown brink eastward, springs–

Because the Holy Ghost over the bent

_____World broods with warm breast and with ah! bright wings.

Hopkins is testing the sundered connection between the natural and divine. “Contemplations” does indeed have several passionately felt stanzas dedicated to the sun; yet this is hardly crypto-pagan nature worship. More to the point, though, those who engage in this reading of “Contemplations” are missing the clear neo-Platonic overtones of the whole poem (thankfully, ; this particular essay makes some similar arguments as mine, but with different concerns).

[Two side-notes for picky readers:

1. For those familiar with Puritan doctrine, it might seem a little strange to connect Bradstreet with the mysticism of Plato, especially inasmuch as it sounds dangerously close to and/or similar ideas which protestants general eschew. This is an impossibly complicated topic to argue here, but I’m hoping to show that the neo-Platonic reading just makes sense. For those who want more of the historical scaffolding, you can return to the aforelinked essay at the end of the previous paragraph, which argues Bradstreet inherited her neo-Platonism from other poets, or you can jump down , which argues that Jonathan Edwards–that arch-Puritan–more or less bought into the analogy of being.

2. For those who think I’m being sloppy with my use of the term neo-Platonism, you’re probably right.]

Other critics have read this passage (along with others in the poem) as Bradstreet conforming to Puritan expectations of feminine weakness. I don’t doubt that patriarchy played some role in shaping this line, but the link to neo-Platonism really helps us see that something else is happening here. Bradstreet’s admission of imbecility is certainly tribute to Bradstreet’s Puritan modesty; but it’s deeper than that: the modesty is also neo-Platonic. Such imbecility is the stupidity of ecstasy. Bradstreet is unable to speak not because she is a woman or because she secretly loves nature more than God, but because one literally cannot speak about these things.

Nevertheless, femininity is an important theme in this poem. The relationship between femininity and ascesis is complex. One sees similar sentiments throughout Interior Castle, in which Theresa constantly chastises her “feminine” inability to be articulate. On the one hand, it is true that such modesty befit the social expectations of femininity in that time; but it is important to note (without denying the marginalizing influence of such expectations) that these expectations contain a subversive corollary: it is only the feminine soul that reaches the heights of ecstasy. According to Theresa, only by not desiring divine gifts can one receive them, can one pass from speech into that deeper eternally spoken Word. That is, only the unassuming, “feminine” soul is actually able to ascend. On a related note, it is no accident that in the very next stanza speaks of crickets and grasshoppers, insects whose classical associations are that of phoenix-like beings entranced by divine song. Bradstreet notes that creatures praise by “their little art” while she remains imbecilic. Bradstreet’s wit here has actually fooled many critics, who assume that on some level she really believes “warbl[ing] forth no higher lays” is a weakness. In fact, this should probably be read as an ironic reproach to the masculine drive to build towers of babble.

But we’re ahead of ourselves. Let’s return to where Bradstreet begins her poem–personal contemplation, a poet called forth into song by the enrapturing beauty of autumn leaves (anyone who has seen the Massachusetts in Fall knows what Bradstreet is talking about):

The trees all richly clad, yet void of pride,

Were gilded o’er by his rich golden head.

Their leaves and fruits seemed painted, but was true,

Of green, of red, of yellow, mixed hue;

Rapt were my senses at this delectable view.

I’ve never taken shrooms, but I’m told they make color “more real,” as if a veil is lifted and one experiences the sensual uninhibited, unmediated. Similarly, Bradstreet sees the colors that seem “painted,” enhanced as if by artifice, and yet they are confoundingly “true.” This vision stirs up the passions within Bradstreet, the appetites. The appetites and their desire to consume completely is unattainable, however. This inability of the human person to fully sate a desire creates a fundamental confusion because the existence of desire implies its object. This confusion is one object of Bradstreet’s contemplations, one focus of her attempt to come to deeper knowledge of being. Therefore, the next stanza begins

I wist not what to wish, yet sure thought I,

If so much excellence abide below,

How excellent is He that dwells on high,

If such desires cannot be sated by the earthly, certainly there is a richness that transcends earthly riches where there can be no barren “winter and no night.” Bradstreet’s gaze then moves upward, from leaves, to sky, to sun, treating each with due reverence. Undoubtedly, Bradstreet is riffing on Augustine’s Confessions:

And what is the object of my love? I asked the earth and it said: ‘It is not I.’ I asked all that is in it; they made the same confession. I asked the sea, the deeps, the living creatures that creep, and they responded: ‘We are not your God, look beyond us.’ I asked the breezes which blow and the entire air with its inhabitants said: ‘Anaximenes was mistaken; I am not God.’ I asked heaven, sun, moon and stars; they said: ‘Nor are we the God whom you seek,’ And I said to all these things in my external environment: ‘Tell me of my God who you are not, tell me something about him.’ And with a great voice they cried out: ‘He made us’. My question was the attention I gave them, and their response was their beauty. (X.vi.9)

Having begun in such contemplation, Bradstreet moves backwards to the story of Eden. She does so by means of that contemplation:

When present times look back to ages past,

And men in being fancy those are dead,

It makes things gone perpetually to last,

And calls back months and years that long since fled.

It makes a man more aged in conceit

Than was Methuselah, Or’s grandsire great,

While of their persons and their acts his mind doth treat.

Again, Bradstreet mirrors Augustine: memory–both personal and historical–is the primary means of introspection and ascension toward the divine. In returning to the palaces of memory, one finds truths that actually transcend the personal, that impart a wisdom preceding one’s individual being (Plato thought the human ability to recognize truth was actually remembering what was forgotten from the previous life of the soul). However, while Augustine travels back to the creation narrative, Bradstreet returns to a time just after creation: Cain and Abel.

To the Night Shark

Past dusk I dived

Fled without flashlight

Went against the current I knew

Would bring me to you

Tooth-skinned from nose to fin

Mortal and counter

Clockwise across you

Skin I gave up to touch

Streamed against the current

One moment still mortal

I was without struggle

without air instinct speech

Skin dissolving between each

Snaggle-toothed stroke

Touch babbling bled

Only then

With the current

Immortal

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=znmhzy6FU6g&hl=en_GB&version=3]

___________________________________________________

Rosebud Ben-Oni is a playwright at New Perspective Theater, where she is currently at work on a new play. Educated at New York University, the University of Michigan and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Ms. Ben-Oni was a Rackham Merit Fellow and a Horace Goldsmith Fellow. She is also co-editor for “HER KIND,” the official blog of “VIDA: Women in Literary Arts”. Her works have appeared in Puerto Del Sol, Arts & Letters, and The Texas Poetry Review. Her first book of poems SOLECISM is forthcoming from Virtual Artists’ Collective in 2013. Find her at rosebudbenoni.com.

The Eggshell Parade brings you a The Noisy Reading Series reading and interview from poet Michael Homolka. Mike reads his poem “Family V,” which appears in the inaugural issue of Phoenix in the Jacuzzi Journal.