Massachusetts writers hold a great position of influence in American writing. Some of this is just a matter of timing: Massachusetts had a kind of head start in fostering talent, and such advantages inevitably become influence (“whosoever hath, to him shall be given, and he shall have more abundance”). But perhaps it’s better not to speak of “influence”; instead, I would claim that Bradstreet divined in the landscape images and structures of being that other American writers would discover and explore.

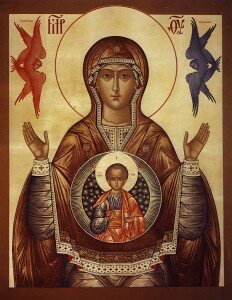

After pondering the act of contemplation, Bradstreet retells the first murder. Cain is depicted as the definitively anti-Christ figure, a cursed newborn enthroned in the lap of Eve (contra images of the theotokos):

After pondering the act of contemplation, Bradstreet retells the first murder. Cain is depicted as the definitively anti-Christ figure, a cursed newborn enthroned in the lap of Eve (contra images of the theotokos):

Here sits our grandame in retired place,

And in her lap her bloody Cain new-born;

The weeping imp oft looks her in the face,

Bewails his unknown hap and fate forlorn;

Stanza 15 tells the story of Abel’s murder:

There Abel keeps his sheep, no ill he thinks;

His brother comes, then acts his fratricide;

The virgin Earth of blood her first draught drinks,

But since that time she often hath been cloyed.

The wretch with ghastly face and dreadful mind

Thinks each he sees will serve him in his kind,

Though none on earth but kindred near then could he find.

This is the bloody inevitability that Frost explored in poems like “Design.” But in addition to her distinctly Massachusetts sensibilities, one can find a propensity toward that broader, particularly American expression of the doctrine of original sin: the social outcast set adrift in a vast and bleak landscape. Stanza 16 describes Cain’s punishment:

His face like death, his heart with horror fraught,

Nor malefactor ever felt like war,

When deep despair with wish of life hath fought,

Branded with guilt and crushed with treble woes,

A vagabond to Land of Nod he goes.

A city builds, that walls might him secure from foes.

Cain is literally branded by God–a marked man, harried by his curse. He is a builder of defensive cities in the wildernes. He cannot farm fruitfully (the ground that drank the blood he spilled refuses him). He lives in constant fear of attack. It is notable that when Bradstreet contemplates sin (something that must be confronted when asceding to God), she does not identify with Adam and Eve, the traditional figures of original sin but with their cursed child. It is easy to forget that there are two events of ‘casting out’ in the first three chapters of Genesis: first, Adam and Eve, cast out for the “spiritual murder” of humankind, and second, Cain, cast out for the literal murder of his brother Abel.

While the marked outcast has been a perennial theme of literature (e.g., The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, etc.), it has found particular resonance in American literature, particularly American literature of the West. My point is not that Bradstreet established the theme of Cain and Abel that later American writers picked up. I suppose it’s possible, but I think it’s much more interesting to say that there’s something in the American landscape and founding psyche, a kind of inverse of the “city on the hill.”

The story of Cain is built into the founding mythos of America, whose people were cast out of Europe to violently master “uncivilized” land (as de Tocqueville observes, “the happy and the powerful do not go into exile”). Consider Moby-Dick, which, despite being set on the ocean, is arguably a story of the proto-modernization of the American west. Like the descendants of Cain, who first use bronze and iron, whaling ships are mini-factories that subdue and process the raw materials of industrialization. A more recent book that memorably retells the myth of Cain in the American context is Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian. McCarthy’s Kid, born with an appetite for blood, “a mindless taste for violence,” is the quintessential marked outcast, “branded with guilt” and pursued by the Judge (a kind of Nietzschen Satan).

Bradstreet’s poem also gestures toward another notable American obsession: Armageddon.

THE FLESH LUSTETH AGAINST THE SPIRIT

This move to the story of the fall and the first murder are necessary for Bradstreet. Being on the edge of what she knew as civilization, Bradstreet had many chances to reflect upon and enjoy the sights of nature. But one who enjoys nature as she does inevitably confronts the ontological fear of death, the finality that nature itself circumscribes. Human persons are driven by appetites, the “delectable view[s]” that enrapture the senses: these passions are primal, the defining experience of embodied beings–we associate them with life, with vitality itself. But they are also fickle, insatiable in any ultimate sense (“Hell hath no limits nor is circumscrib’d”), and, as both ancient Greek and Chinese philosophy realized, the “untutored” pursuit of the passions enslaves us because it places us in a dimension of constant reflexivity, never resting. This is one of the themes of stanza 17:

And though thus short, we shorten many ways,

Living so little while we are alive;

In eating, drinking, sleeping, vain delight.

So unawares comes on perpetual night.

And puts all pleasures vain into eternal flight.

Human life, already a flash, is lessened by pursuit of life. Night comes and satisfaction recedes into its “eternal flight.” In a manner worthy of Solomon, stanza 17 treats of the vanities of human action and pursuits. And also like Ecclesiastes, this recognition moves the poet to consider how the man’s fleeting pursuits contrasts with the seeming inexhaustability of nature (“One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh: but the earth abideth for ever.”). The result of this is stanza 18, which, for my money, is one of the more beautiful articulations of the mystery of death in English:

When I behold the heavens as in their prime,

And then the earth (though old) still clad in green,

The stones and trees, insensible of time,

Nor age nor wrinkle on their front are seen;

If winter come and greenness then do fade,

A spring returns, and they more youthful made;

But man grows old, lies down, remains where once he’s laid.

There are possible echoes of Milton here, but the poem undoubtedly ends with Job:

For there is hope of a tree, if it be cut down, that it will sprout again, and that the tender branch thereof will not cease. Though the root thereof wax old in the earth, and the stock thereof die in the ground; Yet through the scent of water it will bud, and bring forth boughs like a plant. But man dieth, and wasteth away: yea, man giveth up the ghost, and where is he?

In both Ecclesiastes and Job, as well as in Bradstreet, humanity’s ambition to sate its appetites by nature manifests the limits of human persons, exposing the meaninglessness of such pursuits  (“the eye is not satisfied with seeing, nor the ear filled with hearing.”). The depthless void of man’s appetites cannot be filled, even by nature’s unending renewal: this is the sum of ancient wisdom literature. The pain of this realization, profound as the insight is, cannot lead to Bradstreet’s deep “groan in that divine translation” (the piercing and painful sweetness of holy ecstasy). Such a conundrum forces the question: if man cannot be sated by nature, what can possibly fill him? The obvious answer is God–but Bradstreet does not go there quite yet.

(“the eye is not satisfied with seeing, nor the ear filled with hearing.”). The depthless void of man’s appetites cannot be filled, even by nature’s unending renewal: this is the sum of ancient wisdom literature. The pain of this realization, profound as the insight is, cannot lead to Bradstreet’s deep “groan in that divine translation” (the piercing and painful sweetness of holy ecstasy). Such a conundrum forces the question: if man cannot be sated by nature, what can possibly fill him? The obvious answer is God–but Bradstreet does not go there quite yet.

Rather than turning to God, she moves to the undoubtedly zen image of the river: as Siddhartha perfectly demonstrates, the river is an image of the emptiness of Nirvana; it is present at its beginning, middle, and end, and, confounding time, is thus outside of time. It has escaped the vicissitudes of life and therefore can be said to be unchanging, without desire, passionless. Bradstreet addresses the river as “Thou emblem true of what I count the best.” In the river, Bradstreet observes, fish naturally do what they should: “So nature taught, and yet you know not why, / You wat’ry folk that know not your felicity.” The fish is zen; I’m reminded here of Chuang Tzu’s poem, which Merton translated as “The Joy of Fishes.” But, of course, the fish is doubly symbolic as it was the symbol of early Christians. Inasmuch as Christians participate in the life of God, they share the joy of fishes, living in “the peace of God, which passeth all understanding.”

All ascetics must go “through the river,” so to speak. Having pierced the wisdom of the river, Bradstreet’s soul is now ready for its final ascension:

While musing thus with contemplation fed

And thousand fancies buzzing in my brain,

The sweet-tongued Philomel perched o’er my head

And chanted forth a most melodious strain

Which rapt me so with wonder and delight,

I judged my hearing better than my sight,

And wished me wings with her a while to take my flight.

For Augustine, sight is the sense of sensual perception (“the lust of the eyes”). Hearing, however, is the sense of faith. Christ told doubting Thomas “blessed are they that have not seen, and yet have believed.” And Paul says “and how shall they believe in him of whom they have not heard?” In Bradstreet’s Christian tradition, God is not made perceptible through sensual perception (“Thou canst not see my face: for there shall no man see me, and live.”), but only through the testimony of others, through hearing. Bradstreet has been seeing this whole time, observing nature and pondering its sights: this has prepared her heart for what comes by another sense: her soul in the proper state, having reached a sort of Nirvana by the river, can now clearly hear the call of her master’s voice and follow that voice “into a better region, / Where winter’s never felt by that sweet air legion”.

Bradstreet ends the poem, appropriately enough, with an image from Revelation: “he whose name is graved in the white stone / Shall last and shine when all of these are gone.” This is appropriate not simply because it is the end of the poem, the unveiling of all things, but because it channels the apocalyptic geist that has been with America since its inception. The vast and final regions of the United States opened before man a final panorama over which to play out his desire to consume nature. This forces mankind as a whole, like the author of Ecclesiastes, to the “overwhelming question”: “Is there any thing whereof it may be said, See, this is new?“ Or, in other words, what possible thing after this? In the narrative of growth and exploration, America is–in a sense–the last step before that narrative ends or must reinvent itself.

Well written poems, marvelous meaning, and the interpretations in the article are very well done. I appreciate this article very much. If anyone would like to view a sonnet I wrote, I invite you to go to my page below. Thank you.

I have more.

Regibald Inkling